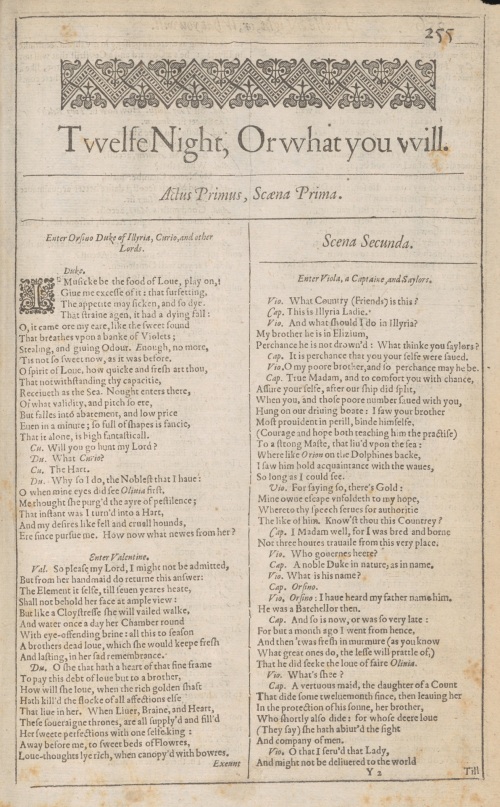

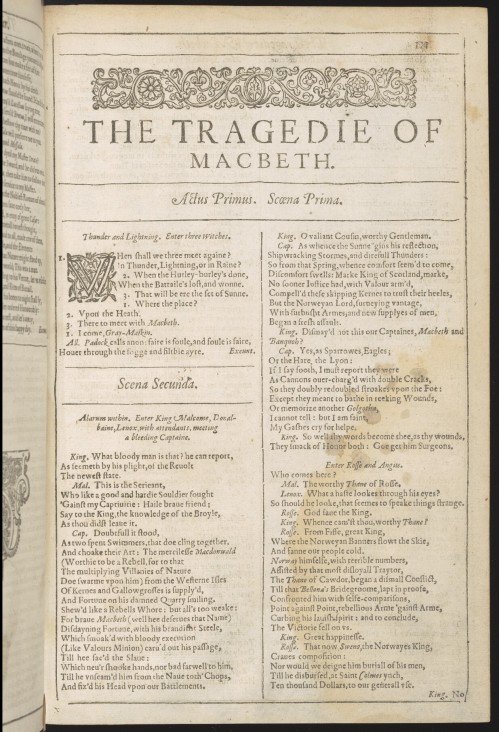

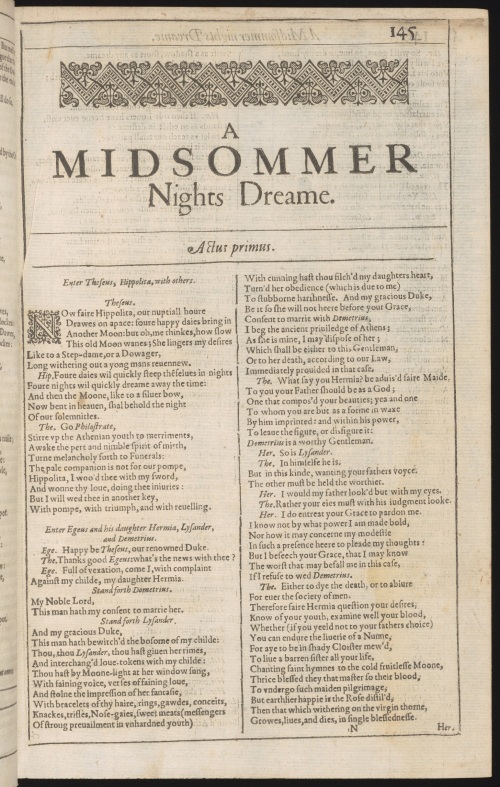

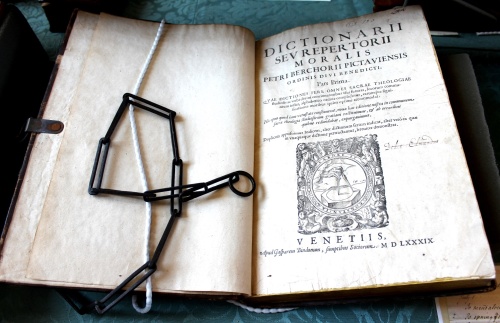

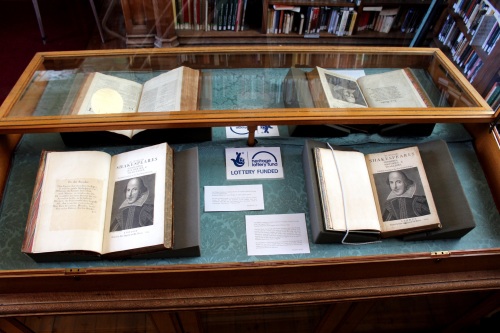

Both in the library and on this blog, we have spent the past year marking the 400th anniversary of the publication of Shakespeare’s First Folio, and it seems appropriate to bring our celebrations to a close on Twelfth Night itself with a look at some of the play’s various manifestations in our library collections.

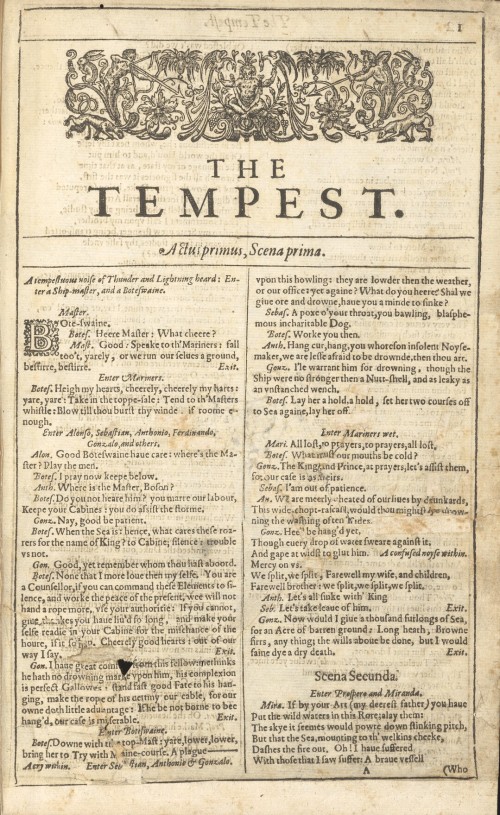

Twelfth Night, or What You Will was written around 1601 but didn’t appear in print until its inclusion in the First Folio of 1623. It’s my personal favourite of Shakespeare’s comedies, so I give particular thanks to the First Folio’s editors Heminges and Condell for rescuing it from likely oblivion.

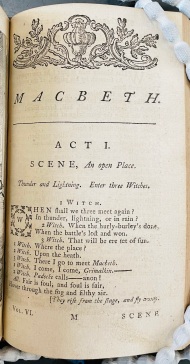

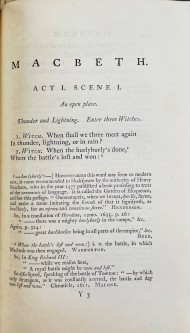

There’s no question about it, the guy knew how to start a play. ‘When shall we three meet again / In thunder, lightning, or in rain?’ (Macbeth.) ‘Now is the winter of our discontent / Made glorious summer by this sun of York.’ (Richard III.) ‘Good day, sir.’ (Timon of Athens.) The memorable opening scene of Twelfth Night sees Orsino, Duke of Illyria, addressing one of his court musicians:

If music be the food of love, play on;

Give me excess of it, that, surfeiting,

The appetite may sicken, and so die.

That strain again! it had a dying fall:

O, it came o’er my ear like the sweet sound,

That breathes upon a bank of violets,

Stealing and giving odour! Enough; no more:

‘Tis not so sweet now as it was before.

O spirit of love! how quick and fresh art thou,

That, notwithstanding thy capacity

Receiveth as the sea, nought enters there,

Of what validity and pitch soe’er,

But falls into abatement and low price,

Even in a minute: so full of shapes is fancy

That it alone is high fantastical.

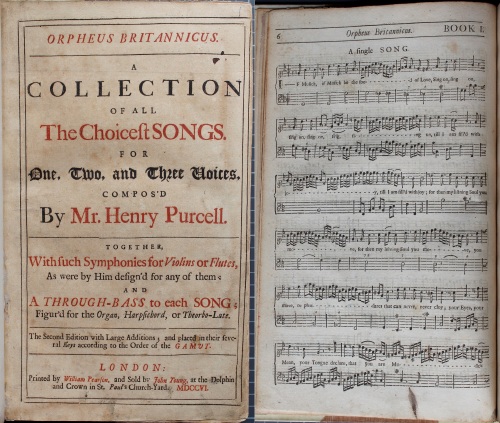

The first line of Orsino’s speech was ‘borrowed’ by the poet Colonel Henry Heveningham (1651-1700) for a lyric opening ‘If music be the food of love / Sing on till I am fill’d with joy.’ Heveningham’s text was set three times by Henry Purcell (1659-1695), the greatest English composer of his generation, one version being included in the huge two-volume compendium of Purcell’s songs Orpheus Britannicus, published posthumously in 1698. The copy below comes from the second edition of 1706 held in the Rowe Music Library.

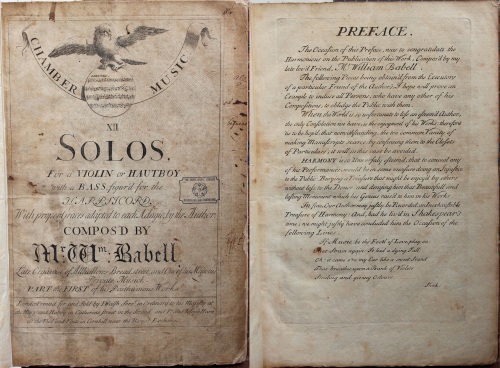

Another posthumous publication in the Rowe with a Twelfth Night connection is a set of sonatas for violin or hautboy (oboe) and harpsichord by the composer William Babell (1690-1723), printed by the noted music publisher John Walsh in 1725. The edition includes a preface by Walsh describing Babell as his ‘late lov’d friend’ and observing that ‘had he liv’d in Shakespear’s time, we might justly have concluded him the occasion of the following lines’, appending Orsino’s words.

Some sources online attribute Babell’s early death to ‘intemperate habits’; this has proved impossible to verify.

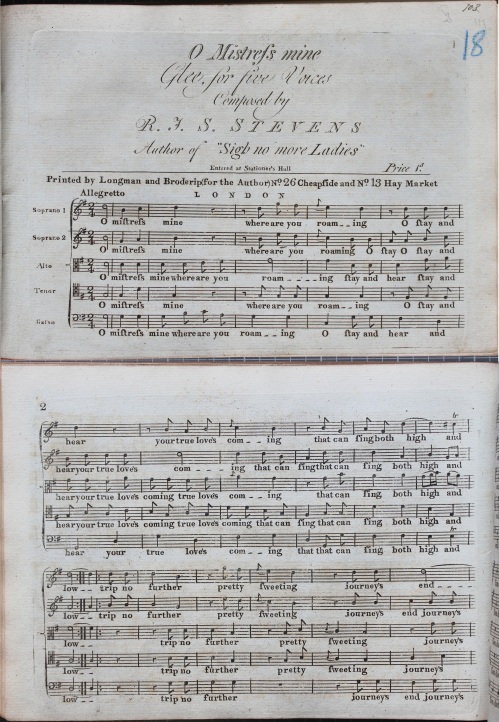

Shakespeare includes a small number of songs in Twelfth Night, all sung by the clown Feste, and three in particular have inspired a multitude of musical settings: ‘When that I was and a little tiny boy’ (with its refrain of ‘For the rain it raineth every day’), ‘Come away, death’, and most popular of all ‘O mistress mine’. The Rowe Library holds a partsong setting of this text, described as a ‘Glee, for five voices’, by R.J.S. Stevens. By the time it was ‘entered at Stationer’s Hall’ on 19 April 1790, Stevens must already have experienced success as a composer of Shakespeare songs, as attested by the legend in the caption title: ‘Author of “Sigh no more Ladies”’.

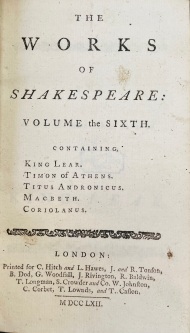

In nineteenth-century Europe there was no shortage of musical stage versions of Shakespeare, the most notable including Mendelssohn’s incidental music for A Midsummer Night’s Dream, Berlioz’s Béatrice et Bénédict (after Much Ado about Nothing) and Verdi’s Macbeth, Otello and Falstaff; but Twelfth Night, perhaps surprisingly, was not a popular choice with composers.

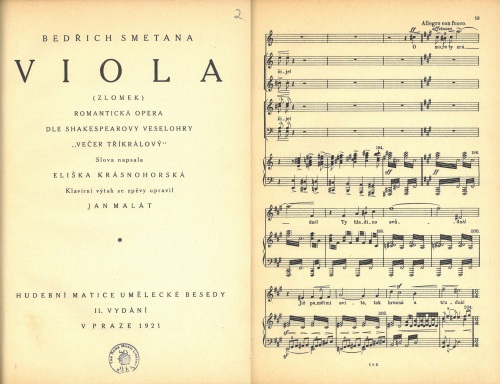

One exception was the Czech composer Bedřich Smetana (1824-1884), who in his final years began work on an opera, Viola, written to a libretto by the young Eliška Krásnohorská. Sadly only fragments of the opera were written. It opens with a shipwreck, followed by a scene between Sebastian and Antonio. The excerpt below shows Viola’s first entry, where she curses the ‘seductive surface’ of the sea she believes has swallowed her brother.

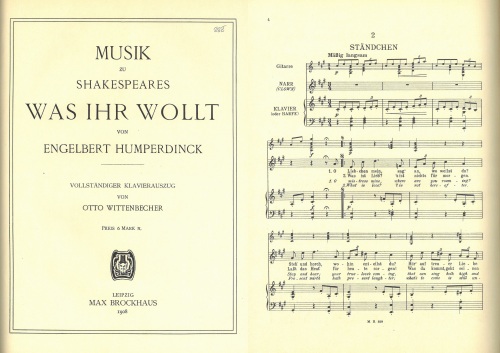

In the early years of the twentieth century, the German composer Engelbert Humperdinck struck up a fruitful partnership with the influential theatre director Max Reinhardt, writing incidental music for four Shakespeare plays staged at the Deutsches Theater in Berlin. The last of these was 1907’s Was ihr wollt, the excerpt below showing the opening of ‘O Liebchen mein’ (‘O mistress mine’), sung by Feste (identified here as Narr, i.e. Clown).

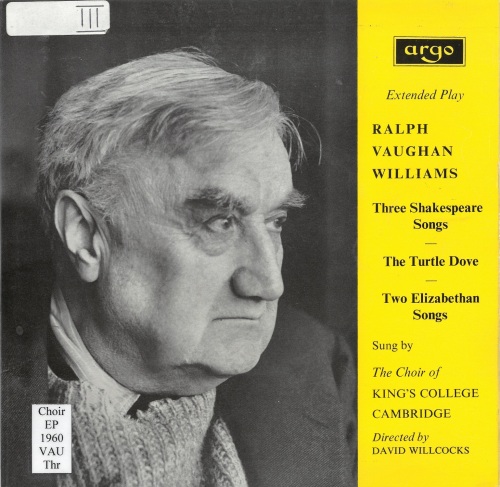

Ralph Vaughan Williams’ light and refreshing partsong setting of the same text dates from 1891 when he was a student at the Royal College of Music. It features on this record from 1960, one of several brightly-coloured EPs released by the choir of King’s College during the early years of David Willcocks’ tenure as Director of Music.

Cover of Ralph Vaughan Williams, Three Shakespeare Songs, The Turtle Dove, Two Elizabethan Songs (Choir.EP.1960.VAU.Thr)

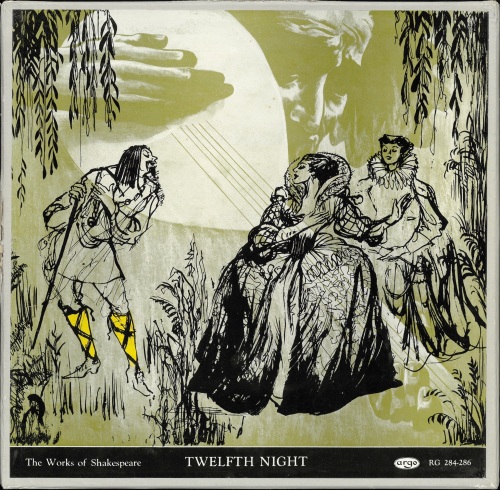

To finish, we return to the play. In the 1950s the British Council commissioned Cambridge’s Marlowe Dramatic Society to record all Shakespeare’s plays for Argo Records using the text of the New Cambridge Edition. This project would culminate in 1964, the 400th anniversary of Shakespeare’s birth. Presiding over the recordings was director George ‘Dadie’ Rylands of King’s, who assembled casts consisting of members of the Marlowe Society and additional ‘professional players’, some of whom had been past members of the Society. The 1961 cast of Twelfth Night included Dorothy Tutin as Viola, Jill Balcon as Olivia, Patrick Wymark as Sir Toby Belch, Prunella Scales as Maria, and the tenor Peter Pears as Feste.

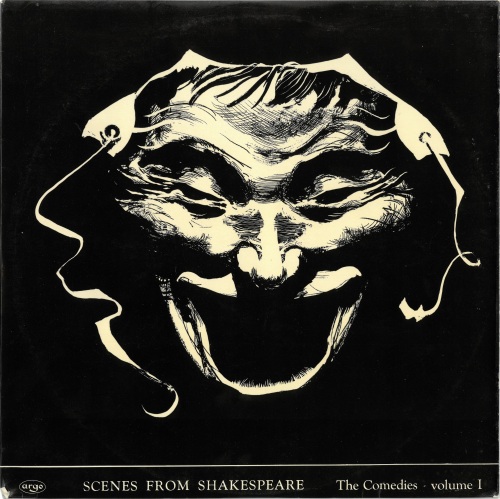

Two excerpts from the Marlowe Society recording of Twelfth Night also feature in this compilation of scenes from Shakespeare’s comedies issued the following year. The fabulous covers of both this LP and the box set above (showing Malvolio in his yellow cross-gartered stockings) were designed by Argo’s in-house designer Arthur Wragg.

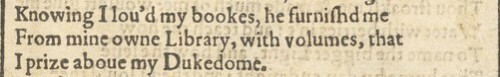

You can browse King’s College’s First Folio on the Cambridge University Digital Library here, and it also features on the First Folios Compared website where you can compare it side by side with other digitised copies of the First Folio.

GB

![Mr. William Shakespeares Comedies, Histories, and Tragedies London: Printed by Tho[mas] Cotes, for Richard Hawkins, 1632](https://kcctreasures.files.wordpress.com/2016/10/second-folio.jpg?w=500&h=478)

![William Shakespeare, The Chronicle History of Henry the Fift London: Printed [by William Jaggard] for T[homas] P[avier], 1608 [i.e. 1619]](https://kcctreasures.files.wordpress.com/2016/10/henry-v.jpg?w=500&h=407)

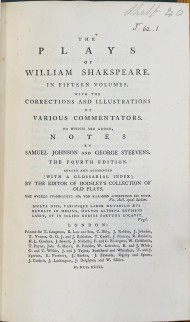

![The Plays of William Shakspeare: In Fifteen Volumes. With the Corrections and Illustrations of Various Commentators. To Which Are Added Notes by Samuel Johnson and George Steevens London: Printed [by H. Baldwin] for T. Longman, et al., 1793](https://kcctreasures.files.wordpress.com/2016/10/shakespeares-will.jpg?w=500&h=414)