It is not unusual to seek refuge in our favourite authors when faced with difficult situations. On the day on which we celebrate the quatercentenary of the First Folio’s publication (8 November 1623), it is timely to remember that Shakespeare’s play The Tempest played an important role in the New Zealand author Janet Frame’s life and writing. Confined to various mental institutions for eight years with misdiagnosed schizophrenia, she used to derive comfort by scribbling lines from The Tempest and poems she loved on the wall of her isolation room, an experience dramatised in her novel Faces in the Water (1961): “With the pencil I wrote on the wall snatches of remembered poems but the pencil applied to the Brick Building wall was like a revolutionary dye that refuses to ‘take’”.[1]

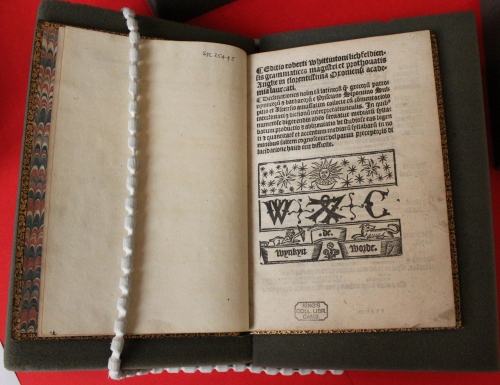

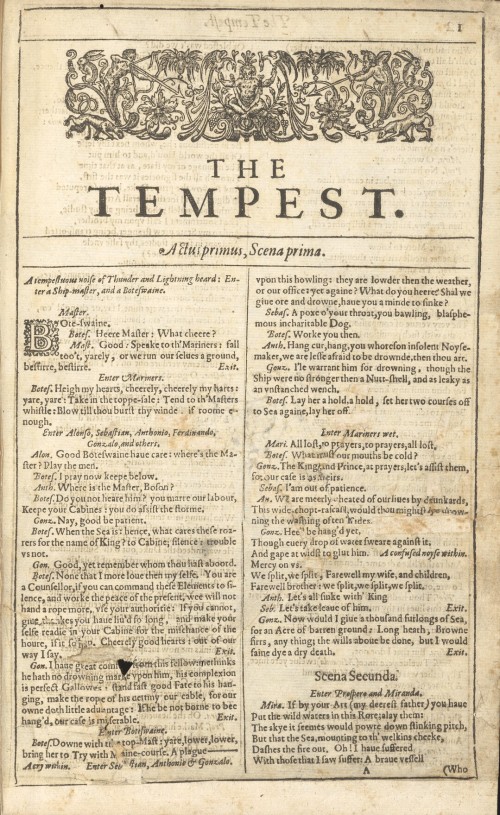

Opening of The Tempest, first published 400 years ago today in Mr. William Shakespeares Comedies, Histories, & Tragedies (London: printed by Isaac Iaggard, and Ed. Blount, 1623; Thackeray.38.D.2). This is one of the plays that might have been lost had it not been included in the First Folio.

The American poet Henry Wadsworth Longfellow found solace in Dante when coming to terms with the loss of his wife, as he confided to his friend Ferdinand Freiligrath on 24 May 1867: “Of what I have been through, during the last six years, I dare not venture to write even to you; it is almost too much for any man to bear and live. I have taken refuge in this translation of the Divine Comedy”.[2]

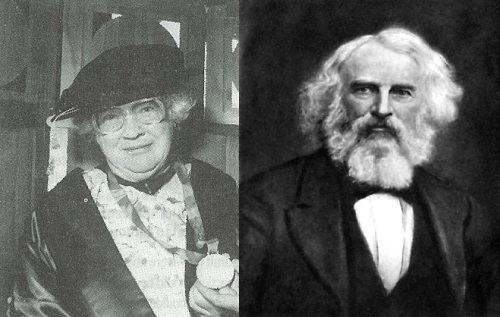

Janet Frame (1924-2004) and Henry Wadsworth Longfellow (1807-82) found comfort in Shakespeare and Dante respectively.

During World War II, another eminent Dante enthusiast, the German critic Ernst Robert Curtius, wrote to Fritz Schalk on 30 October 1944:

Am 18. (sind) alle Fenster und Türen unserer Wohnung kaputt gegangen. Bonn zur Hälfte zerstört, die ‚Insel des Friedens’! Dies & vieles andre deprimiert mich tief. En attendant lese ich Dante & Vergil.[3]

[On the 18th all the windows and doors in our flat were shattered. Bonn half-destroyed, the ‘island of peace’! This and many other things make me feel deeply depressed. En attendant I read Dante & Virgil].

Curtius also commended an eminent German mathematician who began to learn the 14,233-line Divine Comedy by heart during the Christmas of 1914 “um sich über die trübe Gegenwart hinaustragen zu lassen” [in order to get over the bleak present].[4]

King’s College alumnus Gerald Warre Cornish (1874-1916), a classical scholar who was killed in action in France, seems to have coped in a similar way during World War I by immersing himself in the Bible. On his body was found a muddy notebook containing his translations of St Paul’s Epistles, published in 1937 as St Paul from the Trenches: A Rendering of the Epistles to the Corinthians and Ephesians Done in France during the Great War.

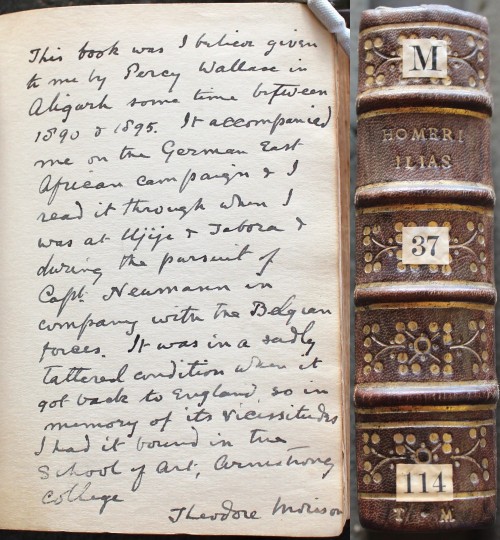

During an earlier war, another classical author, Homer, provided strength to the educationalist Sir Theodore Morison (1863-1936), a graduate of Trinity College, Cambridge, whose copy of the Iliad is in our rare-book collection. His inscription on the flyleaf reads: “This book was I believe given to me by Percy Wallace in Aligarh some time between 1890 & 1895. It accompanied me on the German East African campaign & I read it through when I was at Ujiji & Tabora & during the pursuit of Capt. Neumann in company with the Belgian forces. It was in a sadly tattered condition when it got back to England, so in memory of its vicissitudes I had it bound in the School of Art, Armstrong College. Theodore Morison”:

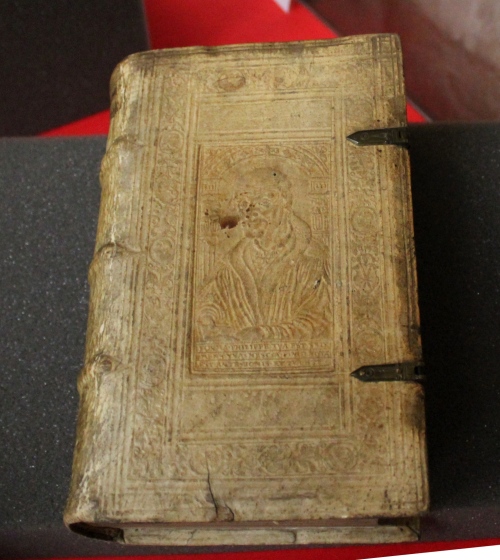

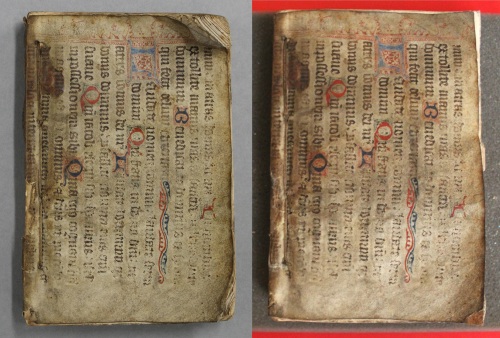

Homērou Ilias (Oxford: J. H. Parker, between 1849 and 1890; M.37.114). Theodore Morison’s inscription and (right) the spine of the rebound book with his gilt initials on the bottom panel. Percy Maxwell Wallace (1863-1943) was professor of English Literature at the Mohammedan Anglo-Oriental College in Aligarh, India between 1887 and 1890. Theodore Morison was the principal at the College from 1899 to 1905. When he returned to England, Morison also served as the principal of Armstrong College in Durham.

The verb “accompanied” is significant as it suggests that the book became a sort of companion in the course of his trials and tribulations, in a way not entirely dissimilar to the role Philosophy played during Boethius’s imprisonment:

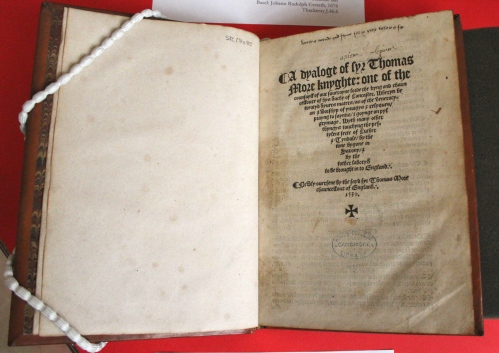

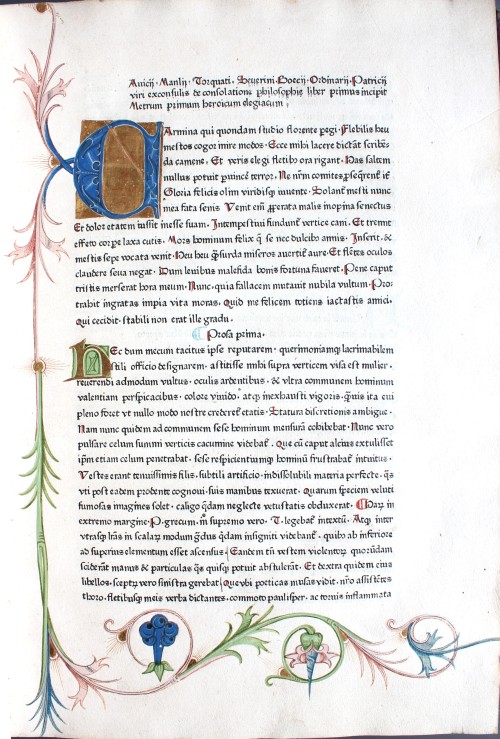

Incipit of Boethius’s De consolatione philosophiae (Nuremberg: Anton Koberger, 1476; Keynes.Ec.7.1.4). The editio princeps was published around 1474, which makes this incunable one of the earliest printed versions of Boethius’s seminal work, where he describes his dialogues with a personified Philosophy on a number of issues including fate, good and evil, and free will.

As we celebrate one of the most important books in English literature today, Prospero’s words to Miranda describing Gonzalo’s kindness in providing them with necessities during the move to the island, aptly summarise the sentiment shared by book lovers as diverse as Janet Frame, Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, E. R. Curtius, G. W. Cornish, and Theodore Morison:

IJ

Notes

[1] Faces in the Water (London: The Women’s Press, 1991), p. 206

[2] Life of Henry Wadsworth Longfellow: With Extracts from his Journals and Correspondence, vol. III, ed. Samuel Longfellow (Boston and New York: Houghton Mifflin, 1891), pp. 89-90

[3] In Willi Hirdt, “Ernst Robert Curtius und Dante Alighieri”, in “In Ihnen begegnet sich das Abendland”: Bonner Vorträge zur Erinnerung an Ernst Robert Curtius, ed. Wolf-Dieter Lange (Bonn: Bouvier Verlag, 1990), p. 181

[4] “Neue Dantestudien”, Romanische Forschungen, 60 (1947), p. 238