In my role as photographer at Cambridge University Library’s Digital Content Unit (DCU), I am fortunate to encounter fascinating and unique material. Digitising the library’s vast collections means that I have handled an early biblical palimpsest, illuminated Persian manuscripts, Japanese painted scrolls, and even a 4000 years old Sumerian clay tablet. That is the nature of the work itself: the ever-changing challenge of utilising high-tech photography to create a digital record of wide-ranging pieces of humanity’s endeavours.

Mid-summer 2022, however, I was given an unusual assignment. King’s College’s precious copy of William Shakespeare’s First Folio needed to be digitised. Although King’s is in sight of the University Library, bringing this invaluable volume to the DCU studio for imaging was not an option. It was decided that I would set up a mobile studio in the college library to photograph the First Folio over a two-week period.

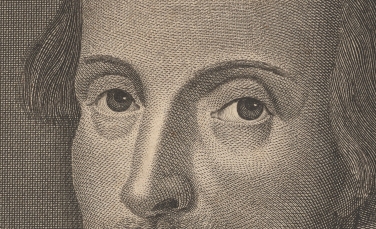

Mr. William Shakespeare’s Comedies, Histories, & Tragedies (also known as ‘the First Folio’) hardly needs any introduction, especially during the year in which we celebrate the quatercentenary of its publication. Gathering 36 of Shakespeare’s plays, it was published in 1623, seven years after the playwright‘s death. Its literary significance cannot be overstated. Notably, as some original manuscripts were lost over the centuries, the Folio constitutes the earliest record for 18 plays, including some of Shakespeare’s most famous works such as Macbeth and The Tempest. Out of the 235 known First Folio copies disseminated around the world, four are held by Cambridge University institutions, including the one in King’s College. The green leather-bound volume with gold embossing is only slightly taller than an A4 sheet of paper. An engraving of the Bard’s likeness adorns the frontispiece, followed by over 900 pages of text. As Dr James Clements, College Librarian, remarked, it was striking to think that I would be the first person to look closely at (and turn) every single page of the book in many decades, or perhaps a few hundred years.

Close-up of the First Folio frontispiece portrait of William Shakespeare engraved by Martin Droeshout.

One September morning, my colleague Gordon McMillan drove me and a van load of photography equipment across the river. With the assistance of another peer, Błażej Mikuła, I took possession of the space which would become my office for the coming weeks. It was a seminar room on the second floor of the library. The octagonal space was entirely lined with glass-fronted cabinets packed full of rare books. To install my mobile digitisation studio, I moved chairs to the sides and I used the large, solid-wood round table as a sturdy base on which to place a traveller’s book cradle. This device provides extensive support for fragile and precious bound items. Nestled between the cradle’s boards, the book is mostly held down by gravity and a weighted string (known as a snake) keeps it open in the right place. A clear acrylic sheet propped up by foam blocks ensured that the targeted page stayed flat, while minimising the pressure on this historic binding. It is important that the item being captured sits parallel to the camera in order to produce a non-distorted image.

Camera setup in the seminar room. The PhaseOne camera is on a tripod looking over the traveller’s book cradle, on which rests the First Folio, with flash lights on both sides.

The high-resolution camera (a 100-megapixel PhaseOne digital back with a 120mm prime lens) was mounted onto a heavy-duty tripod and the spot for the tripod’s legs was marked on the rug with black tape. The two Broncolor flash lights flanking the camera, equipped with soft boxes, received the same treatment. I tied laptop tethering and all power cables together and out of the way so that they would not constitute a trip hazard. It was crucial to prevent setup disturbances throughout the imaging process to guarantee a consistency of imaging. While this is easier to achieve in a traditional photography studio where lights and book cradles are fixed, replicating it from scratch in a room which has not been designed for it requires a whole lot more effort.

The imaging started with exposure and colour calibration. I tested the positioning of my flash lights, as well as potential reflections. This highlighted the need to cover the camera brand name and other elements which were reflecting in the acrylic sheet. The angle of the lights was adjusted to account for the fact that this traveller’s book cradle sits in the opposite direction to what its larger relatives would in a photography studio. These light and colour parameters remained unchanged during the entire digitisation process. A meticulous workflow results in extremely accurate and detailed digital reproduction. Images do not need to be retouched through post-processing software. A frustrating side effect was that I also had to limit stray light by closing the window shutters while photographing, thus depriving me of the delightful views of Webb’s Court!

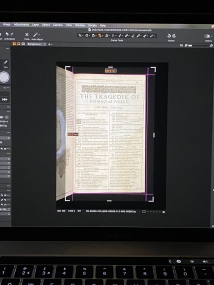

The first page of ‘The Tragedie of Romeo and Iuliet’ on my laptop screen during the digitisation. The white snake is visible on the left of the image, outside the cropped area which will constitute the final image.

Regularly checking that the image was in focus, I photographed the front cover first, followed by the rectos of each page, interleaving them with a black background. Once all the rectos were imaged, I flipped the book over and repeated the process, capturing the versos including the back cover. Before I knew it I came across the words uttered by Hamlet ‘To be or not to be…’. It was hard not to read every famous passage of these seminal plays. Finally, the spine and gilt top and bottom edges were recorded, therefore creating a complete digital copy of the volume. Importantly, I double (and triple) checked the hundreds of files before dismantling the mobile studio, as indeed, the exact photography conditions would all be near impossible to reproduce once they were taken apart.

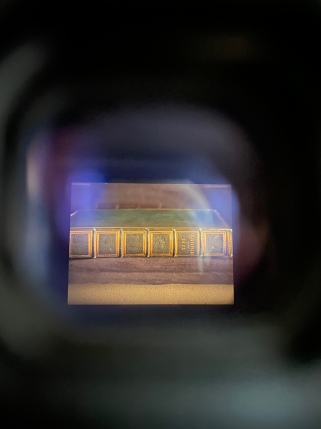

The First Folio book spine as seen through the camera viewfinder. ‘Shakespeare – 1623’ is embossed in gold.

The beauty of King’s College and its various locations is something I found myself constantly in awe of during the fortnight I spent there. Whether it was a river Cam view from a library window, the beautiful display of modern paintings on the south wall of the dining hall (talk about a backdrop for fish and chips on Friday), or, of course, the glorious fan vaulting of the college’s chapel ceiling, it remains one of the greatest aspects of my job. Finally, I would be remiss if I did not mention another undoubtable highlight of my mission: meeting the staff of King’s College Library. I was very appreciative of all of them for making me feel welcome, inviting me to join their tea breaks and lunches, and for telling me about their work. I was particularly grateful to James Clements for all his help and kindness. His behind-the-scenes tour of the library was fascinating, and I was touched that he took time out of his busy schedule to show me around.

The King’s College First Folio is fully digitised and accessible online on this link.

Amélie Deblauwe

Not only does today mark the anniversary of Rupert Brooke’s death, it also marks the launch of a new online resource which offers unprecedented access to his archives.

Not only does today mark the anniversary of Rupert Brooke’s death, it also marks the launch of a new online resource which offers unprecedented access to his archives.