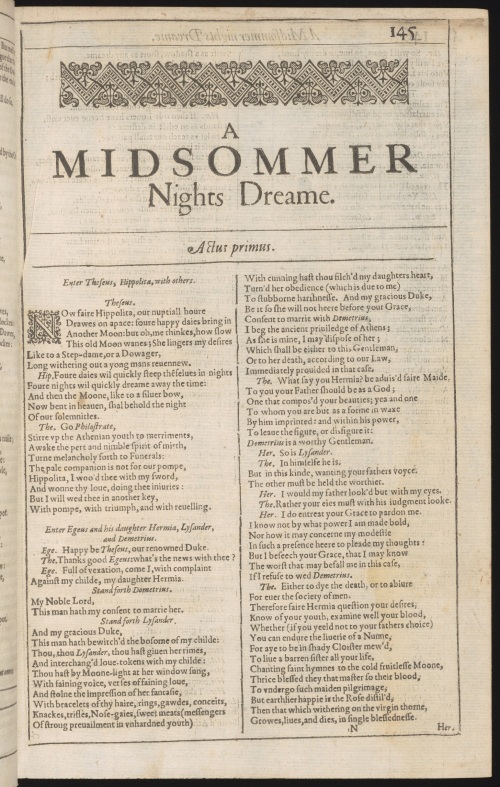

To continue our series of blog posts marking the 400th anniversary of Shakespeare’s First Folio, now seems a particularly opportune time to take a look at A Midsummer Night’s Dream, written in the mid-1590s. The text of the play in the First Folio of 1623 is based mainly on that of the second quarto edition of the play, printed in 1619.

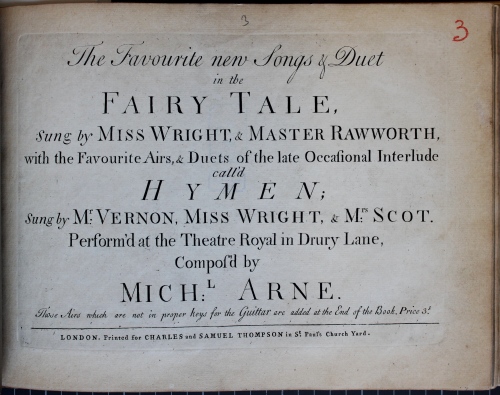

Sadly at King’s we have no copy of either quarto, but we do have an 18th-century curiosity: The Favourite New Songs & Duet in the Fairy Tale, composed by Michael Arne (son of Thomas ‘Rule, Britannia!’ Arne), and printed by Charles and Samuel Thompson in St Paul’s Church Yard, London, in 1764.

To put The Fairy Tale in context, we need to go back to 1760s London. Actually, let’s go back a century earlier, to Monday 29 September 1662, when Samuel Pepys went out on the town:

I sent for some dinner and there dined, Mrs. Margaret Pen being by, to whom I had spoke to go along with us to a play this afternoon, and then to the King’s Theatre, where we saw “Midsummer’s Night’s Dream,” which I had never seen before, nor shall ever again, for it is the most insipid ridiculous play that ever I saw in my life. I saw, I confess, some good dancing and some handsome women, which was all my pleasure.

(Is there an entry in Pepys’ diaries where he doesn’t mention handsome women? I salute the horniest man of the English Restoration.)

In case your memory needs refreshing, A Midsummer Night’s Dream has several interconnected plots, chief among them a dispute between Oberon and Titania, King and Queen of the fairies, a romantic intrigue between four young lovers, Helena, Hermia, Demetrius and Lysander, and the rehearsal of a play by a group of amateur actors (described by the fairy Puck as ‘rude mechanicals’).

The literary scholar George Winchester Stone, Jr., writing in 1939, suggests that the unorthodox mixture of realistic material (the mechanicals), classical mythology and fairy lore was ‘bound to fail in presentation’, which may account partly for the variety of reinventions of the play in the decades that followed Pepys’ disappointing visit to the King’s Theatre.

By the mid-18th century the Theatre Royal, Drury Lane was thriving under the command of actor-manager David Garrick. Taking his cue from the pageants fashionable at the time, Garrick’s first Theatre Royal production of A Midsummer Night’s Dream, in 1755, took the guise of an opera called The Fairies, which boasted music by John Christopher Smith (advertised as ‘pupil to Mr. Handel’), two Italian singers for the arias, and a troop of boys for the fairies.

Garrick’s collaborator on this production was the dramatist George Colman (sometimes known as ‘George the First’ to distinguish him from his identically named son), who seems to have been the driving force behind The Fairy Tale, first staged on 26 November 1763. Whereas The Fairies of 1755 focused largely on the two pairs of lovers and cut the mechanicals entirely, The Fairy Tale, judging by the published script, is the reverse. The lovers are nowhere to be seen, and the script is only about a quarter of the length of A Midsummer Night’s Dream as it appears in the First Folio.

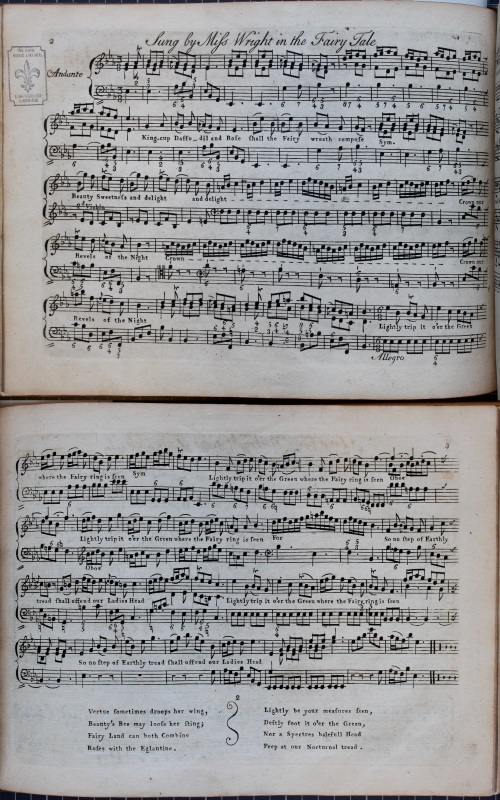

The reason for this drastic abridgement may have been to make room for instrumental and vocal numbers. The four songs that appear in the published score of The Favourite New Songs & Duet in the Fairy Tale are three solo arias, ‘Kingcup, daffodil and rose’ (‘sung by Miss Wright’), ‘Yes, yes, I know you, you are he’ (ditto), and ‘Come follow, follow, follow me’ (‘sung by Masr. Rawworth’), along with a duet, ‘Wellcome, wellcome to this place’ (sung by both together), none of them to texts by Shakespeare.

The script contains about fourteen songs or likely songs. These include a number of verses from the original play, such as ‘Over hill, over dale’, ‘You spotted snakes’, ‘Up and down, up and down’ and ‘Flower of this purple dye’, and also, to round things off, ‘Orpheus with his lute’ (borrowed from Henry VIII) and ‘Sigh no more, ladies’ (borrowed from Much Ado about Nothing). Why do none of these more familiar texts appear in the Favourite Songs volume? Perhaps because in the production they were sung to pre-existing and already popular musical settings.

Most of the songs in The Fairy Tale, even those belonging to particular characters in Shakespeare’s play, are assigned to either ‘1st Fairy’ (Miss Wright) or ‘2nd Fairy’ (Master Rawworth), which suggests these two were specialist singers. The identity of Master Rawworth (called Raworth in the play text) is hazy, but Miss Wright is undoubtedly the soprano Elizabeth Wright, whom Arne eventually married in November 1766. Her performance must have been a success: over the next three and a half years The Fairy Tale received forty-one performances at the Theatre Royal, and in 1777 it was revived at the Haymarket Theatre, which had just been bought by Colman.

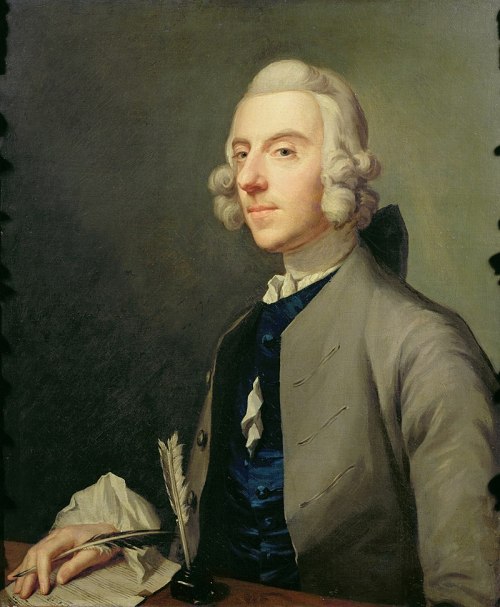

The end of Michael and Elizabeth Arne’s marriage has a hint of Shakespearean tragedy about it: in 1768, perhaps emboldened by their joint success at the Theatre Royal, where Elizabeth had become a leading lady, Arne built a laboratory at Chelsea for the study of alchemy, but went bankrupt and found himself in debtors’ prison; Elizabeth died the following year, with the writer Charles Burney, a friend of the family, claiming that Arne had ‘sung [her] to death’. Arne himself died destitute in 1786.

Portrait of Michael Arne in happier days by Johan Zoffany, c. 1765. Image from Wikimedia Commons

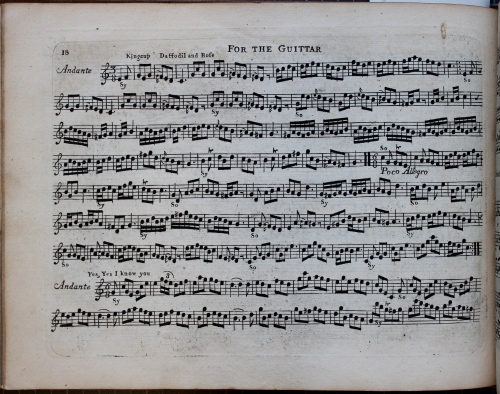

To end on a sunnier note, the Favourite Songs volume ends with an appendix containing transposed ‘guittar’ parts for all songs not written in ‘proper’ keys. So on page 18 we find a guitar part in C for ‘Kingcup, daffodil and rose’, originally written in the unfriendly key of E flat. The presence of guitar parts brings home the purpose of this publication: to enable performance outside the context of the play. It is pleasing to think of these modest but attractive songs having a life beyond Drury Lane, perhaps at public pleasure gardens (such as Ranelagh Gardens in Chelsea, where Michael Arne first saw Elizabeth Wright sing in 1763), or even in the home.

Guitar part for ‘Kingcup, daffodil and rose’ from The Favourite New Songs & Duet in the Fairy Tale (Rw.85.118/3)

References

Cholij, I.B. (1995). Music in Eighteenth-Century London Shakespeare productions. PhD thesis, King’s College, University of London.

Parkinson, J.A. (2001). ‘Arne, Michael.’ Grove Music Online [subscription only]

Stone, G.W., Jr. (1939). ‘A Midsummer Night’s Dream in the Hands of Garrick and Colman’. PMLA, 54, 467-482.

You can browse King’s College’s First Folio on the Cambridge University Digital Library here, and it also features on the First Folios Compared website where you can compare it side by side with other digitised copies of the First Folio.

GB