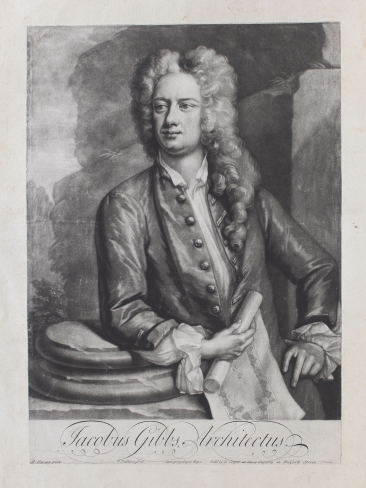

James Gibbs, A Book of Architecture, Containing Designs of Buildings and Ornaments (London: 1728), frontispiece. (Shelfmark: F.27.7)

Three hundred years ago today, on the 25th March 1724, the foundation stone was laid for a new building in King’s, known today as the Gibbs Building, named after the architect James Gibbs (1682–1754) who designed it. We are fortunate to know quite a lot about the events of that day because of the survival of certain items in the special collections in King’s Library.

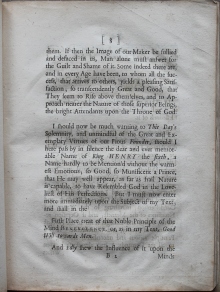

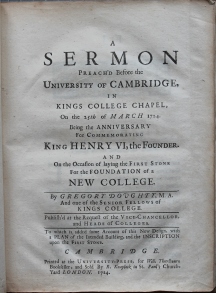

Proceedings began with the sermon before the university in a special service in Chapel given by senior King’s fellow Gregory Doughty (ca. 1690–1742, KC 1706). We know exactly what the sermon was, because it was published, and the publication also reveals other aspects of the service and the ceremony which followed.

A Sermon Preached Before the University of Cambridge in King’s College Chapel on the 25th of March 1724 … by Gregory Doughty (Cambridge, 1724), title page. (Shelfmark: C.5.44.(3.)

The subject of the sermon was ‘Luke II.14 Good Will Towards Men’, and much space was given to extolling the virtues of acts of benevolence, particularly that of founders and patrons of learned societies such as Cambridge colleges. It being ‘Founder’s Day’ (it was celebrated on 25th March at the time), several passages praise Henry VI, the founder of King’s: ‘We must account it sure as well the peculiar felicity, as glory of this society, to be bless’d with such a sovereign for its founder; who prefer’d the honor and service of his Maker to all the gay and flattering privileges of Crown’, writes Doughty.

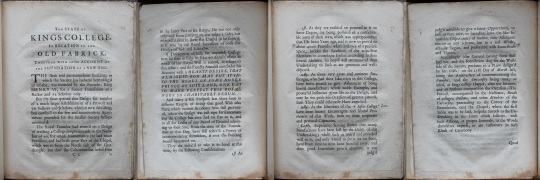

A Sermon Preached Before the University, appended section ‘The State of King’s College in Relation to the Old Fabrick’. (Shelfmark: C.5.44.(3.)

Appended to the sermon is a document entitled ‘The state of King’s College, in relation to the old fabrick, together with some account of the foundation of a new one.’ This document points out that the new building was long overdue, given the old buildings were intended only for Henry’s original foundation of a community consisting of ‘a rector and 12 scholars’ which he had soon abandoned in favour of a community of ‘a Provost and 70 fellows and scholars’. Towards the end of the document there is an interesting account of the foundation ceremony which took place immediately after the service in Chapel:

Accordingly (the Ground having been first laid out, and the Foundation dug for the West-side of the Square, pursuant to a PLAN design’d by Mr Gibbs) on 25th Day of March last, being the Anniversary of Commemorating the Founder, and the University being met, as usual, at King’s College Chappel; after the Sermon, and an Anthem compos’d on the Occasion; The Provost, accompanied by the Noblemen, Heads of Colleges, Doctors, and other Members of the University, proceeding to the Corner, where the first Stone was to be laid, bespoke Success to the Undertaking in the Form which follows, with such Actions, at proper Intervals, as the Words themselves express, or are customary in such Kinds of Ceremony.

The words ‘in the form which follows’ were printed in Latin at the end of the sermon publication, and reveal a number of interesting details, most notably that some of the words were engraved on a bronze plate and, together with some gold, silver and bronze coins, were put into the foundation stone of the building. The story becomes more intriguing when the text goes on to explain that ‘If in future years a student of ancient times, while searching through the rubble, unearths this bronze plate encased in stone, may he know that this stone was destined for the construction of this College in the times of Henry VI.’

A Sermon Preached Before the University, final two pages comprising the Latin words read out at the foundation ceremony together with an English translation. (Shelfmark: C.5.44.(3.)

The famous clergyman and antiquary William Cole (1714–1782), if his version is to be trusted, sheds light on this stone that had been ‘destined for the construction of this college in the times of Henry VI’:

When the news came of the Founder’s deposition the labourers who were sawing the stone in halves and not having finished it, imagining that there would be no further proceeding in the design by his successors left of their work and the stone remaining half sawed in two. This was always the story about the stone which I myself have seen before any design of making the use of it which was afterwards thought on; and a cut of that stone is in the print of this chapel engraved by David Loggan. In the cleft part was the plate and inscription with ye different coins put. (See British Library, Add MS 5802, fol. 110)

Here is Loggan’s engraving. You can see the stone, partly sawn in half, on the grass on the right-hand side of what was then known as ‘Chapel Yard’:

King’s College Chapel engraved by university engraver David Loggan (1634–1692) (Reference: JS/4/10/38)

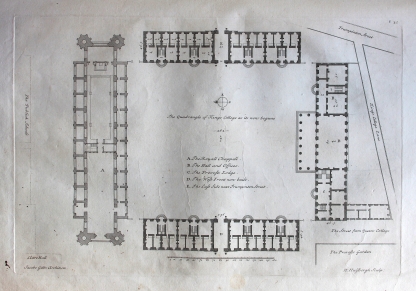

Gibbs, A book of Architecture, plate 32 showing the plan for the ‘West Front’ (the Gibbs building) and the front court. (Shelfmark: F.27.7)

Regarding the gold, silver and bronze coins that were enclosed with the engraved bronze plate, there is a centuries-old tradition of burying contemporary coins in the foundations of new buildings in the belief that it would bring good luck and prosperity. How tantalising it is to know that these coins and the engraved plate are buried in the foundations of the Gibbs building but we are not able to see them today! William Cole also tells us that when digging the foundations of the Gibbs building apparently a number of coins from the reign of Henry V were discovered:

at ye digging of the foundation for the aforesaid new building a large quantity was supposed, tho’ not 100 were owned to have been found by ye workmen & labourers, who were thought to have disposed of them otherwise, of gold coins of King Henry ye 5th & others, which were as was surmised, hid by ye people in those troublesome times; for where ye present new building stands, was formerly a large street, call’d Mill Street … These coins were sent by ye College to ye benefactors to this building as presents, & a very few remain in ye Treasury as a memorial. (BL Add MS 5802, fol. 115)

Indeed, the following is a photograph of a coin (a groat) from the reign of Henry V which is still in the College’s collections, and is perhaps one of those dug from the ground when laying the foundations for the Gibbs building:

The conclusion of the inscribed Latin words printed with the sermon which discusses ‘literary monuments more lasting than this bronze plate’ (‘Monumenta Literaria, Hoc Aere perenniora . . .’) is a clear allusion to Horace’s Odes 3.30 which begins ‘I have completed a monument more lasting than bronze . . .’ (‘Exegi monumentum aere perennius’). The author will have known his audience, and this allusion to Horace will not have been lost on them.

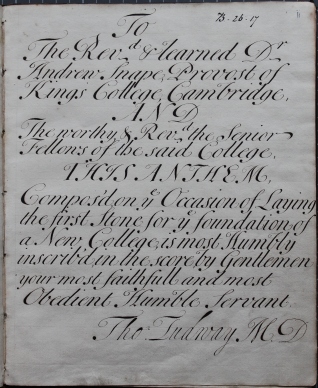

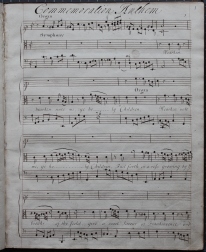

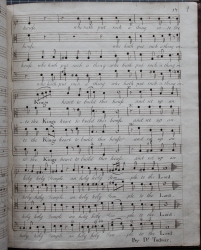

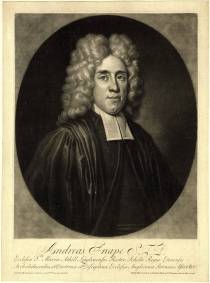

We saw above that ‘an Anthem compos’d on the occasion’ was mentioned in the published sermon, and this brings us to our second item in the Library’s special collections. The anthem in question is ‘Hearken unto me ye holy children’ by the composer Thomas Tudway (before 1650–1726), professor of music in the university and organist at King’s from 1670 until 1726. The original manuscript is held in the Rowe Music Library in King’s. It is a verse anthem, scored for three soloists and choir, and the copy in King’s Library is clearly a presentation copy that begins with a dedication to Provost Andrew Snape (1675–1742, KC1690) and the fellows of the College:

The text of the anthem is made up of a variety of verses from several books of the Bible including Ecclesiastes, Ezra and the Psalms. Its sentiments resonate with the themes of the sermon as you would expect:

Blessed be the Lord God, of our fathers, who hath put such a thing into the King’s heart, to build this house.

to be a Father to the Fatherless, to feed them with the bread of understanding, & give them the waters of wisdom to drink

His name shall endure for ever, His name shall remain under the sun among the posterities

Provost Andrew Snape (engraving by John Faber, between 1696 and 1721. King’s Archive reference: KCAC/1/4)

Thomas Tudway holding a page of an anthem he has composed for King’s College Chapel. (Bate Collection of Musical Instruments, University of Oxford).

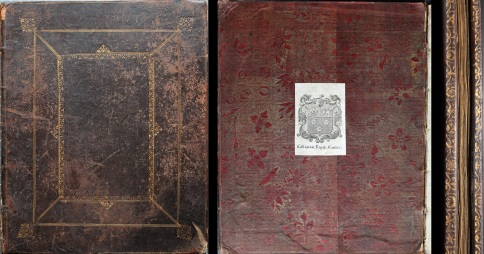

Several aspects of the binding of the volume point towards its importance and uniqueness as a presentation copy. It is a leather-bound volume with a panel design tooled with gold borders with fleuron decorations stamped in gold on the front and back boards. The foredges of the binding are also tooled in gold, as are the text block edges. No expense has been spared. Unusually, the pastedowns—which are usually simply plain hand-made paper—are in this case made of a much more expensive paper embossed with a red and gold floral design.

Tudway, Hearken Unto Me, Front panel binding with gold tooling (left), Inside front pastedown embossed in red and gold (centre), Front fore-edges of binding and text block decorated in gold (right). (Shelfmark: Rowe MS 108)

One would think that something as special as this would have been treasured in King’s, but curiously, by one means or another, the manuscript ended up being owned by one Henry Robson in the early nineteenth century who gave the volume to his cousin John Henry Robson in 1833. Thankfully it was returned to King’s by a relative, a Mrs Robson, in 1852.

Alas, this reminds us of the dilemma faced by William Cole who had spent eighteen years in King’s meticulously documenting our history, but when deciding where to deposit his manuscripts in 1788, he wrote ‘I have long wavered how to dispose of all my manuscript volumes; to give them to King’s College, would be to throw them into a horsepond; and I had as lieve do one as the other; they are generally so conceited of their Latin and Greek, that all other studies are barbarism.’ A little harsh perhaps, but rest assured that the librarians and archivists in King’s today take great care in looking after the special collections and are delighted to be able to share them with you on special days such as today!

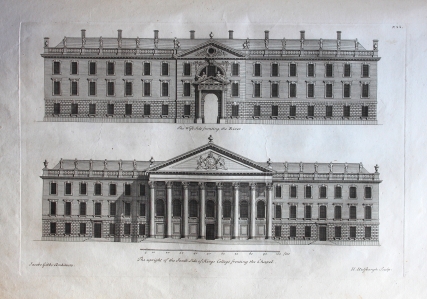

Gibbs, A Book of Architecture, plate 35 showing the designs for the Gibbs building. (Shelfmark: F.27.7)

An early eighteenth-century theodolite by London instrument maker Richard Glynne (1681–1755), active ca. 1707 to 1730, belonging to King’s. A record in the College archives shows that we purchased a theodolite in 1724, presumably for building the Gibbs building. Could this be the one? (The theodolite is on long-term loan to the Whipple Museum in Cambridge. Reference: Wh.6588)

JC

________________________