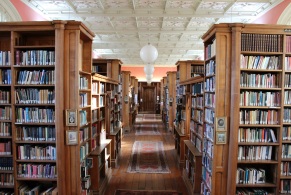

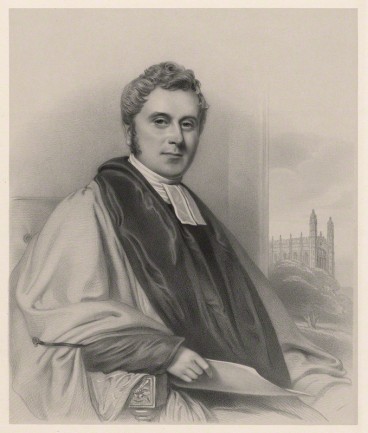

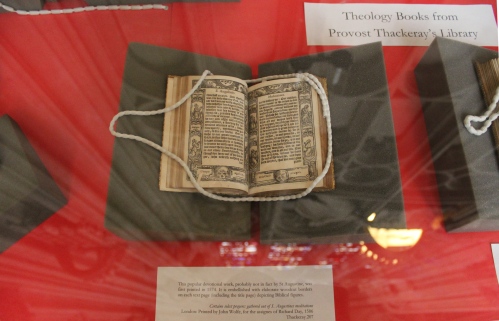

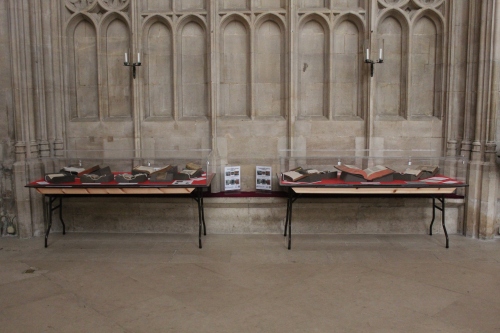

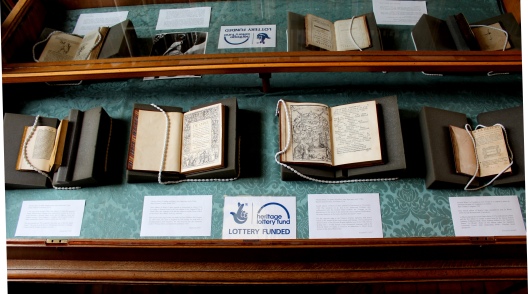

The last exhibition as part of our HLF-funded project was mounted in the beautiful setting of King’s College Chapel in May and June 2018, and it featured books from the theology section of George Thackeray’s library. When he died in 1850, he left his black-letter divinity books, mostly printed between 1530 and 1580, to King’s in his will (some 165 volumes). His daughter Mary Ann Elizabeth bequeathed the rest of her father’s library to the College in 1879. Over 22,000 people visited the Chapel in May and June, but for those who did not have the opportunity to see the exhibition, we provide here some selected highlights.

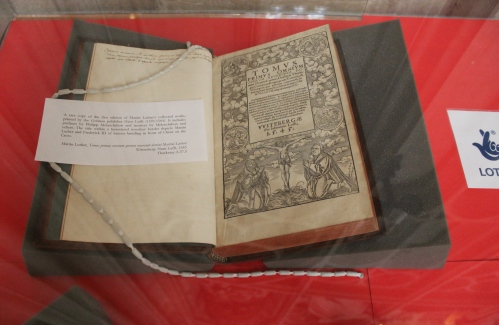

If you look closely at the next two images, you’ll be able to see the reflection of the chapel wall and the stained glass windows on the cases. This is volume I of the first edition of Martin Luther’s collected works. The title within a historiated woodcut border shows Martin Luther and Frederick III of Saxony kneeling in front of Christ on the Cross:

Martin Luther, Tomus primus omnium operum reuerendi domini Martini Lutheri

Wittenberg: Hans Lufft, 1545

(Thackeray.A.37.5)

This devotional work, first printed in 1574, was likely not authored by St Augustine. Each page has elaborate woodcut borders depicting Biblical figures:

Certaine select prayers: gathered out of S. Augustines meditations

London: Printed by John Wolfe, for the assignes of Richard Day, 1586

(Thackeray.207)

One of the most prolific and influential of Germany’s early printers, Anton Koberger (ca. 1440-1513) printed fifteen editions of the Latin Bible at Nuremberg between 1475 and 1513. Dated 10 November 1478, Koberger’s fourth Latin edition contained several pointers for readers, for example the first table of contents indicating the folio number on which each book of the Bible begins:

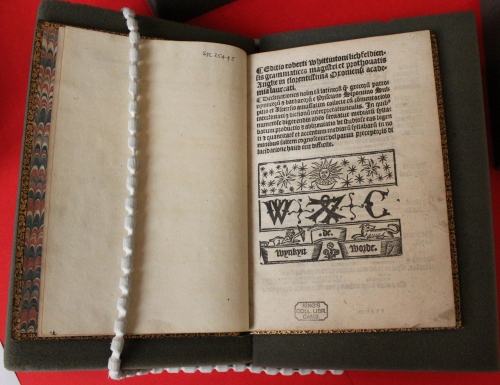

The grammarian Robert Whittington was best known for his elementary Latin school books. This 1517 edition of Declinationes nominum [The Declension of Nouns] was produced by the celebrated printer Wynkyn de Worde (died ca. 1534), who collaborated with William Caxton and took over his print shop in 1495. The title page has one of Caxton’s distinctive printer’s devices incorporating the words “wynkyn .de. worde”:

Robert Whittington, Editio roberti whittintoni … Declinationes no[m]i[nu]m ta[m] latinoru[m] [quam] grecoru[m]

London: Wynkyn de Worde, 1517

(Thackeray.41)

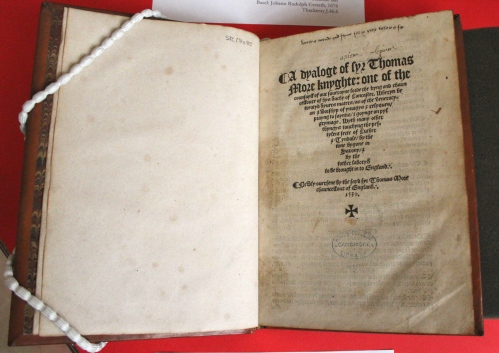

This second edition of Sir Thomas More’s Dialogue concerning Heresies, in which he asserts the Catholic Church as the one true church, contains a contemporary 16th-century inscription on the title page (uncertain reading): “lone to amende and fayne for to plese lothe to a[?]f”:

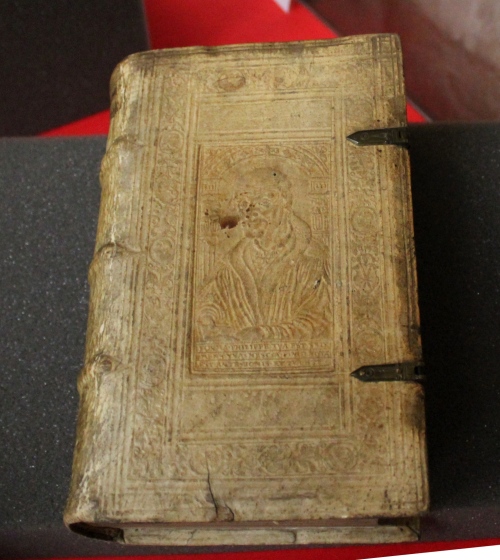

The exhibition also included a selection of books remarkable because of their bindings. This copy of Philipp Melanchthon’s Orationum (1572) features a characteristic 16th-century German blind-stamped alum-tawed pigskin binding over wooden boards. On the front board is a portrait of Melanchthon, with the lines: “Forma Philippe tua est sed mens tua nescia pingi nota est ante bonis et tua [scripta docent]” [Philipp, this is your likeness, but your mind remains unknown to good men without the teaching of your writings]:

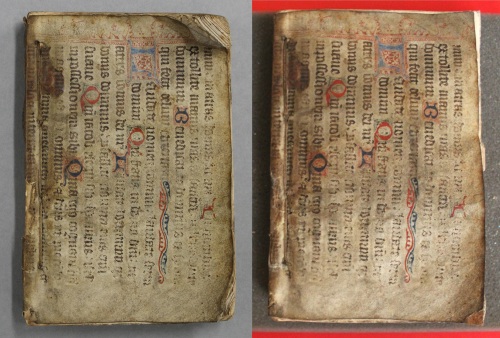

This small volume is bound in a parchment wrapper with manuscript writing on both sides and initials illuminated in red and blue. Recycling of manuscripts in book binding was a common practice. Thanks to the HLF grant, the binding has been repaired as shown in these images, before (left) and after (right) conservation:

William Fulke, A confutation of a popishe, and sclaunderous libelle

London: Printed by John Kingston, for William Jones, 1571

(Thackeray.182)

We would like to take this opportunity to thank the HLF for their generous support over the past two years, which enabled us to catalogue almost 2,000 books from the Thackeray Bequest, repair the volumes that required conservation, create a digital library, organise school visits, and mount numerous exhibitions which attracted thousands of visitors.

IJ

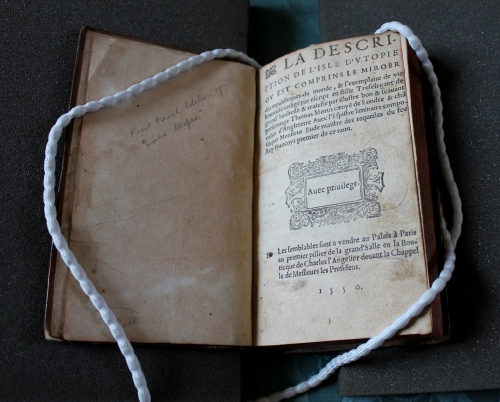

![Thomas More, De optimo reipublicae statu, de[que] noua insula Vtopia [Paris]: Gilles de Gourmont, [1517] (Keynes.Ec.7.3.15)](https://kcctreasures.files.wordpress.com/2017/03/keynes-ec-7-3-15.jpg?w=500&h=381)

![Thomas More, De optimo reip[ublicae] statu, deque noua insula Vtopia Basel: Johann Froben, March 1518 (Thackeray.J.46.7)](https://kcctreasures.files.wordpress.com/2017/03/thackeray-j-46-7.jpg?w=500&h=345)

![Thomas More, De optimo reip[ublicae] statu, deque noua insula Vtopia Basel: Johann Froben, November 1518 (Keynes.Ec7.03.17)](https://kcctreasures.files.wordpress.com/2017/03/keynes-ec7-03-17.jpg?w=500&h=316)

![Thomas More, A frutefull pleasaunt, & wittie worke, of the beste state of a publique weale, and of the newe yle, called Utopia London: [Richard Tottel for] Abraham Vele, [1556] (Keynes.Ec.7.3.18)](https://kcctreasures.files.wordpress.com/2017/03/keynes-ec-7-3-18.jpg?w=375&h=527)

![Ambrosius Holbein's engraving of the island of Utopia in Thomas More's De optimo reip[ublicae] statu, deque noua insula Vtopia (Basel: Johann Froben, March 1518) Thackeray.J.46.7](https://kcctreasures.files.wordpress.com/2016/11/more-utopia-1518_engraving.jpg?w=229&h=353)