If the Marie Hartwell blog piqued your interest in the College livery, read on for a snapshot of the livery provision in her time.

The 22nd Founder’s Statute[1] allows for a clothing allowance, or livery.

The statute declares that ‘With a view to the unanimity of the fellows, and a stronger mutual bond of affection when they see that they are outwardly all the same, and to increase their affection for the College from which they receive so much help, as well as to prevent any defect in garments which may render them notorious with the other Scholars of the University, the members are to have similar garments but cut according to their condition and degree.’ The Provost is to have 12 yards for his (and his household), the Fellows’ and scholars’ portions are also specified. ‘All the cloth for fellows, scholars, chaplains, clerks and choristers is to be well made, 24 yards in length and about 2 yards in breadth, and not to exceed the sum of £87 in toto.’ Multi-coloured or unclerical clothes are forbidden, as are those ‘made in the silly modern fashion with slashes and folds and shoulder pads’.

It is unlikely that individuals in the current College community would ‘wear’ the proposal that a College uniform would improve their mutual affection, let alone the desirability of uniformity itself. And notoriety among other ‘Scholars of the University’ can be achieved by more interesting means than defective garments.

The existing annual accounts (the accounts for years ending 1502, 1505, 1506, 1512–1515, 1517–1518, and 1520–1524 do not survive) show that the Hartwells were typical of our College drapers for that time: when dates of payment are given they are mostly around May and November; the prices per yard for the various qualities of fabric are about the same, and we generally bought about 350–450 yards a year, paying about £60 until the late 1510s when we began to pay everyone (not just the Provost and a couple of others who procured their own livery) their liberata allowance in cash rather than fabric.

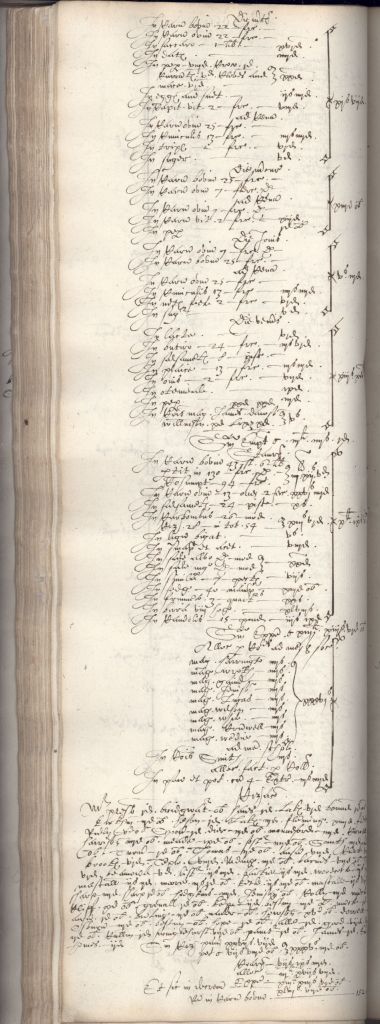

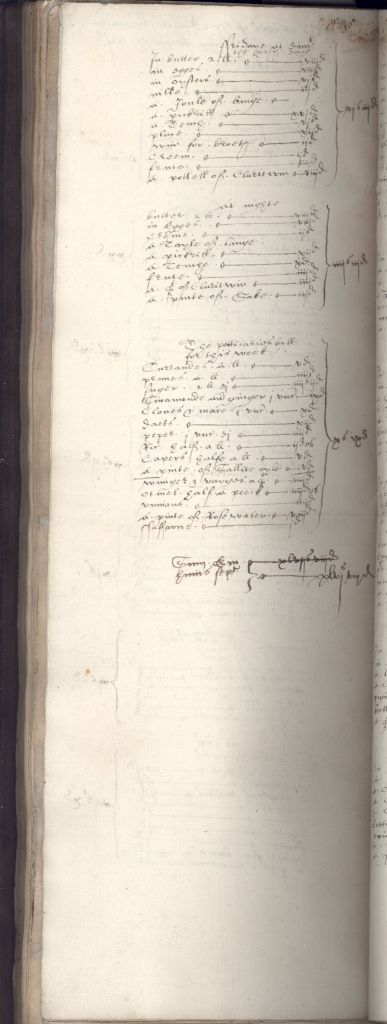

The above image showing the livery expenditure page from the 1506–1507 annual accounts book is typical for the period—and very pretty it is too. After the livery allowances dispensed in cash, the list of livery fabric purchases begins (the sixth item on the list) with a payment to Thomas Hartwell for ‘tawney medley’. There follow a number of lots at a cost per yard of between 2 shillings 4 pence and 5 shillings. It is reasonable to suspect that the same supplier, i.e. the Hartwell firm, supplied all of the cloth listed that year, in the same colour scheme (mixed tans).

Thomas being named at the top suggests, but by no means proves, that he was still alive when it was written, which might have been as early as September 29th 1506, narrowing down his time of death to sometime between September 29th and November 30th, 1506 (see the Marie Hartwell blog post)—but that assumes several things including that the clerk copying down the expenses knew of Thomas’s death when it happened. Not every sixteenth-century widow would bother to reprint her invoice forms immediately upon being widowed.

The due date on the College’s bond to Marie Hartwell, for 27 pounds 11 shillings 4 pence, fell in this financial year. It is not the case that the first few entries, nor the last few, add to that figure, and the list is in decreasing value of cloth. This suggests that the cloth was bought in mixed lots, at least two tranches every year, with the final reckoning set out at the end of the financial year.

Table: Existing information about the supply of College livery, 1499–1525

| YEAR | PAYEE | EXPENDED (l.s.d) | YARDS | COLOUR |

| 1499–1500 | Mr Hartwell, London draper | 59.0.8 | ||

| 1500–1501 | Master Bond of Coventry | 55.7.5 | ||

| 1502–1503 | No name listed | 55.19.2 | 342½, and 12 | unknown, and black cotton |

| 1503–1504 | Thomas Bonde | 51.13.11 | 318¼ | |

| [1504–1505] | Thomas Hartwell | at least 58.10.15 as paid on two bonds | ||

| [1505–1506] | Marie Hartwell | at least 29.14.0 as paid on a bond | ||

| 1506–1507 | Marie Hartwell | 55.1.0 | 334¼ | tawney medley |

| 1507–1508 | William Hartwell, citizen and Draper of London | 57.13.3 | 356¼ | brown tawny |

| 1508–1509 | Marie Hartwell | 57.18.8 | 348½ | blue |

| 1509–1510 | Marie Hartwell | 61.18.3 | 369 | violet |

| 1510–1511 | Haddon of Coventry | 67.19.6 | 446¾ | tawny |

| 1515–1516 | No name listed | 76.18.½ | 489½ | |

| 1518–1519 | Richard Hal. | 74.8.3 | 444¼ | russet |

| 1524–1525 | John Smith of Walden | 6.9.3 | 29½ | tawny; servants and choristers only |

From the financial year 1524–1525 at the latest we bought cloth only for the servants and choristers and gave the Fellows, scholars, chaplains and clerks their livery allowance in cash.

It is interesting to note en passant that the existing College accounts suggest that the livery in the first quarter of the sixteenth century was often tawny but could also be russet, violet or blue.

The Drapers Guild records are online[2] and show that in 1477 one Thomas Hartwell got his Freedom by servitude (under master William Holme). Presuming that he’s the only Thomas Hartwell, Draper of London (as the online records suggest) and that he’s ‘ours’[3], he had several Apprentices including a Henry Glossop. The two post-1506 entries for Thomas (who we know died in 1506) were for the Freedoms of his son William[4] and his apprentice Henry Glossop.

The only other H(a/e)r(t/d/)(e/)wel(l)s on the Drapers online records are: a Bryan Hartwell who in 1515 got his freedom (by Redemption), a Thomas Hertewell who had some apprentices c 1485 and may in fact be our same Thomas, a Richard Harwell in 1518 having an Apprenticeship, a Robert Hartwell who in 1532 was a new apprentice (to Thomas Pettitt) and so is probably not Thomas’s son, and a ‘(Female) Hartwell’ who got her freedom in 1509. It’s tempting to think that was Marie, but there is no evidence for this in the Drapers online records.

Is it a coincidence that the Draper Thomas’s son is called William, like one of our Kingsmen? It was a common enough name in the early sixteenth century but it is tempting to think that it suggests the Kingsmen Hartwell brothers (William, Thomas and John) are near relations of, but not the same as, the Draper Hartwells (Thomas and William).

To sum up the two blogs on this subject: the College archives show that the early College donor Marie Hartwell was the widow of Thomas Hartwell, Draper, of London. That firm supplied the cloth for the College livery in 1499–1500 (possibly through the agency of a Kingsman related to them) and again from Michaelmas 1505 to Michaelmas 1510; when Thomas died in 1506 his wife, and/or his son William, carried on. Thomas was possibly a near relation to the Kingsmen William, Thomas and John Hartwell all of London, and probably brothers. The recorded gifts to the Chapel from three Hartwells are from Marie, and possibly others among her near in-laws or sons. The reasons for the donations are not recorded.

PKM

[1] Henry VI is said to have written the King’s College statutes, which were in force until 1862. The archives include a translation of parts of them into English (KCS/69), from which this is taken.

[2] https://www.londonroll.org/search (accessed 1 Sep 2022)

[3] https://www.londonroll.org/about (accessed 1 Sep 2022) says that during this time Citizenship of London (our draper Thomas is usually so described) could only be obtained through membership of a Livery Company.

[4] https://www.londonroll.org/about (accessed 1 Sep 2022) also says that the main routes to becoming a member/Freeman of a Livery Company were servitude (apprenticeship), patrimony (the children of Freemen qualified for membership) and redemption (you could buy your Freedom).

![The beginning of statute 22 from an early copy (c 1500) of the Founder’s statutes [KCS/54 fo 23v]](https://kcctreasures.files.wordpress.com/2022/09/kcs-54-f-23v-stat-22-start.jpg?w=500&h=271)

![Livery expenditure for 1506-07 [KCAR/4/1/1/9 fo 19r]](https://kcctreasures.files.wordpress.com/2022/09/kcar-4-1-1-vol-9-liberata-1506-7-fo-19r.jpg?w=500&h=623)

![Bond dated 1 January, due 30 November 1505 [KCAR/3/3/1/1/1 fo 195v]](https://kcctreasures.files.wordpress.com/2022/09/kcar-3-3-1-1-1-195v-thom-h-1-dsc09376.jpg?w=500&h=207)

![Bond dated 15 January, due 8 September 1507 [KCAR/3/3/1/1/1 fo 205r]](https://kcctreasures.files.wordpress.com/2022/09/kcar-3-3-1-1-1-205r-widow-h-dsc09379.jpg?w=500&h=143)