On 18 July 2017, the 200th anniversary of Jane Austen’s death, King’s College Library mounted an exhibition featuring first editions of all of Austen’s novels, the autograph manuscript of her unfinished novel Sanditon, a manuscript letter to her publisher, a book from her library, early translations of her novels, and other rare treasures. The event was a great success and was attended by over 1,000 people. Some of this material was used in our Open Cambridge exhibition which attracted over 1,400 visitors during the weekend of 8-9 September. We present below some highlights from the second part of the exhibition for those who could not visit in person.

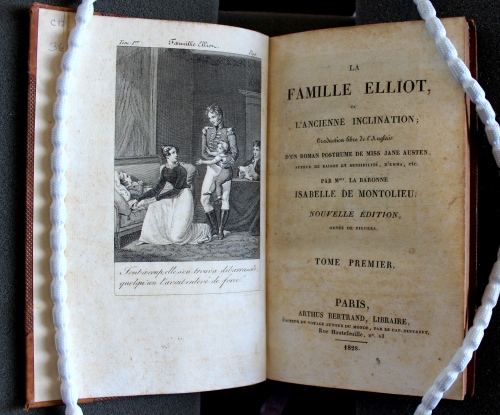

Persuasion was first printed in French in 1821. This copy of the second French edition (1828), freely translated by the Swiss novelist and translator Isabelle de Montolieu (1751–1832), belonged to Sir Geoffrey Keynes, the younger brother of John Maynard Keynes.

Jane Austen, La Famille Elliot ou l’Ancienne Inclination

(Paris: Arthus Bertrand, 1828)

Gilson.A.PeF.1828/1

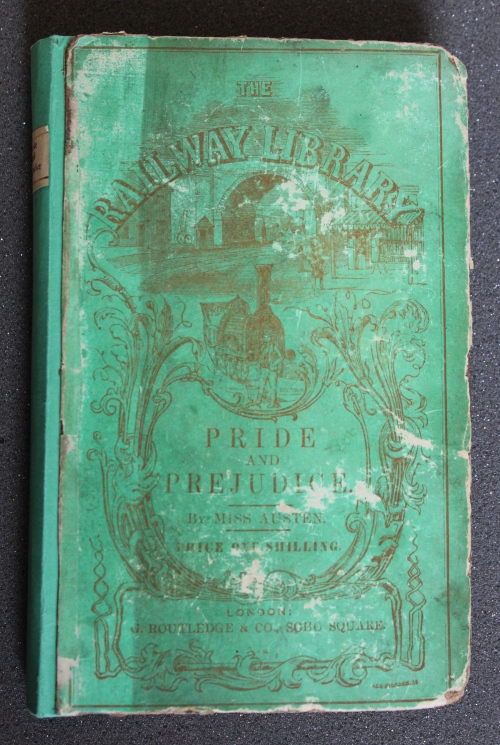

Routledge’s Railway Library, intended for ‘amusement while travelling’, began in 1849 as a shameless imitation of Simms and McIntyre’s Parlour Library. The inclusion of Pride and Prejudice in the series in 1850 is a testament to the popularity of the novel at the time.

Pride and Prejudice. By Miss Austen, ‘The Railway Library’

(London: Routledge, 1850)

Gilson.A.Pr.1850a

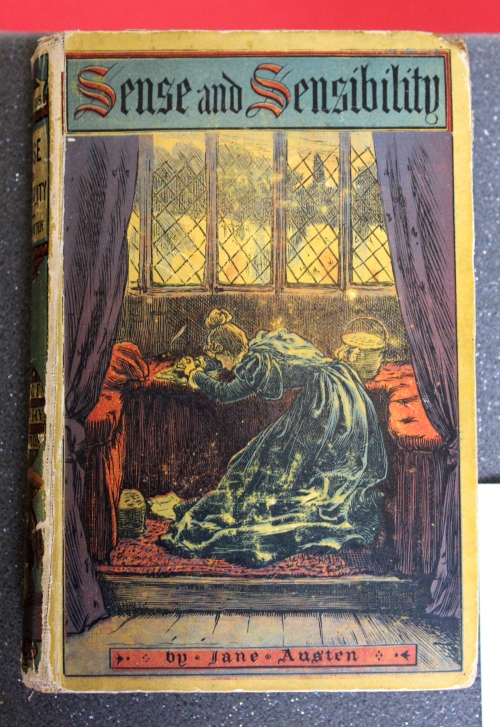

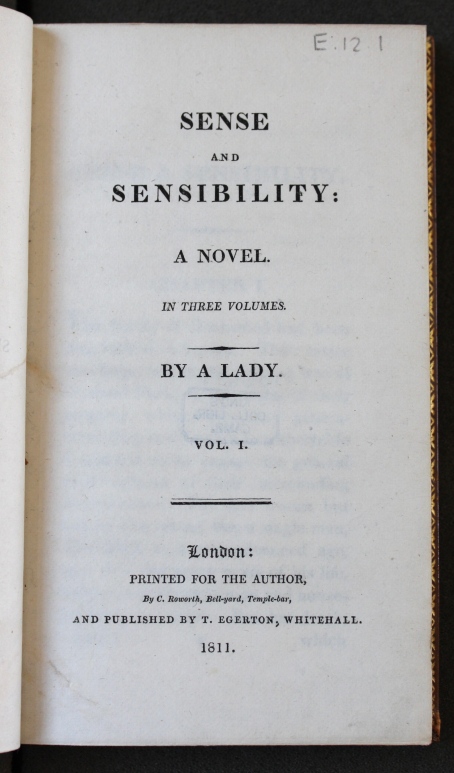

Chapman and Hall’s series ‘Select Library of Fiction’ was closely associated with W.H. Smith, who carefully sought out copyrights, or reprint rights, of popular novels in order to publish yellowback editions for sale on his railway bookstalls. The series, which ran from 1854 until it was taken over by Ward, Lock in 1881, included at least thirty novels by Anthony Trollope, who had strong views on the poor quality of much railway literature. This is one of the few known copies of Sense and Sensibility in yellowback.

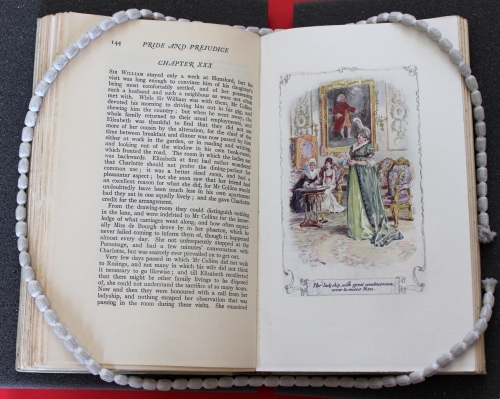

Lady Catherine is fully aware of her station in life and had no qualms in making others aware of this. This edition of Pride and Prejudice is illustrated by the Cambridge-based artist Charles Edmund Brock.

Jane Austen, Pride & Prejudice

with twenty-four coloured illustrations by C. E. Brock

(London: Dent, 1907)

Gilson.A.Pr.1907b

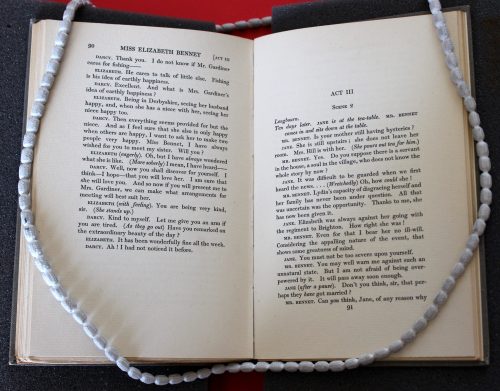

In this scene from A. A. Milne’s stage adaptation, Jane and Mr Bennet discuss Lydia’s elopement with Mr Wickham, fully aware of the social implications and prospects for the family as a result.

A. A. Milne, Miss Elizabeth Bennet: A Play from “Pride and Prejudice”

(London: Chatto & Windus, 1936)

Gilson.A.Pr.Z.Mil

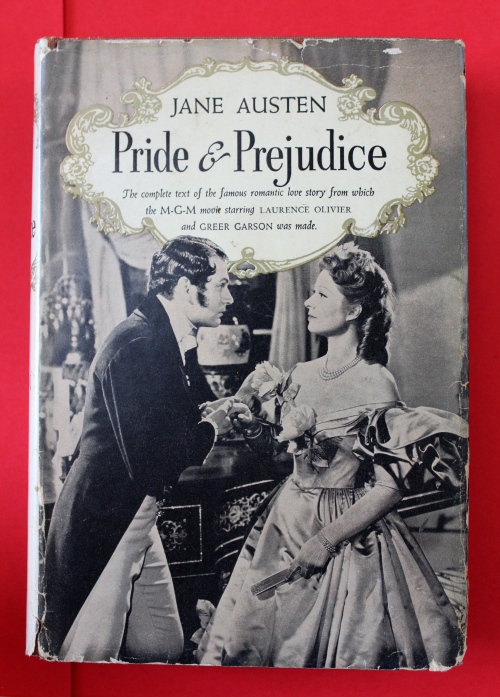

The 1940 film adaptation of Pride and Prejudice, starring Greer Garson and Laurence Olivier, is notorious for drastically diverging from the novel and being excessively ‘Hollywoodized’ — and for putting the women in clothes based on the styles of the late 1820s and 30s. This publication, which coincides with the release of the film, bears the subtitle: ‘The complete text of the famous romantic love story from which the M-G-M movie starring Laurence Olivier and Greer Garson was made’.

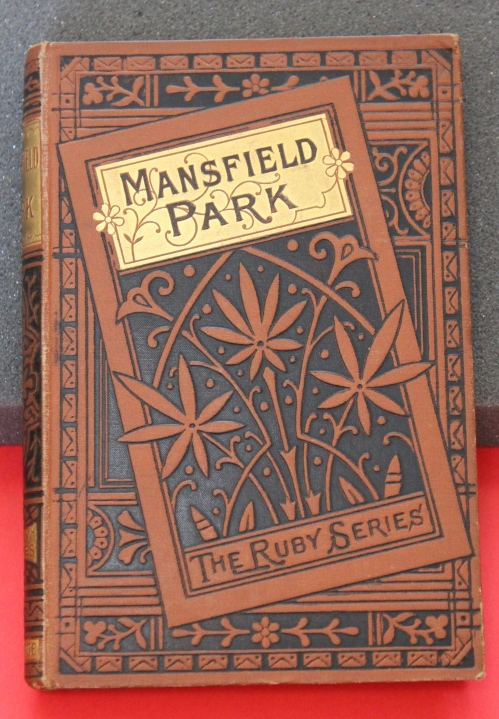

This Victorian edition of Mansfield Park was presented to E. M. Forster’s mother by his father, and was later inherited by Forster himself.

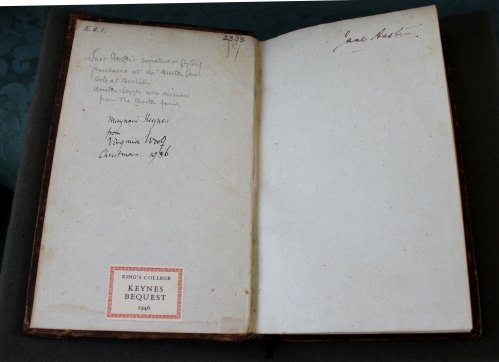

One of the highlights in the exhibition was Jane Austen’s copy of Orlando furioso, signed by her on the fly-leaf, sold by the Austen-Leigh family, bought by Virginia Woolf, and inscribed by Woolf to John Maynard Keynes at Christmas 1936.

Ludovico Ariosto, Orlando furioso (trans. by John Hoole)

(London: Charles Bathurst, 1783)

Keynes.E.4.1

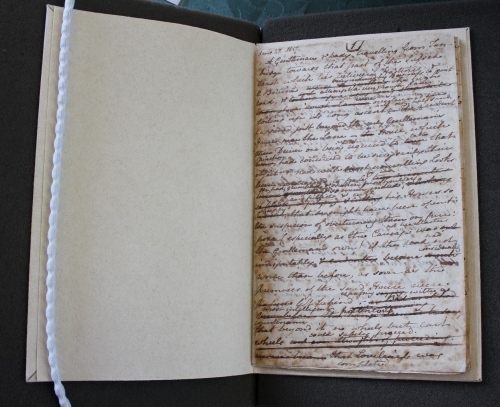

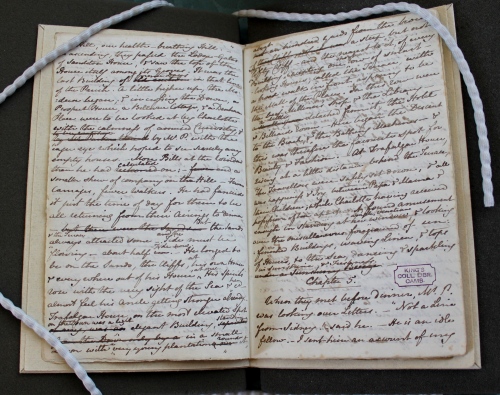

King’s College owns the manuscript of Jane Austen’s unfinished novel Sanditon, the last one on which she was working before she died on 18 July 1817. It is a rare surviving autograph manuscript of her fiction. It was given to King’s in 1930 by Jane’s great-great niece (Mary) Isabella Lefroy in memory of her sister Florence and Florence’s husband, the late Provost Augustus Austen Leigh who was a great-nephew of Jane. The booklets were made by Austen herself. The last writing is dated 18 March 1817. She died four months later.

IJ/Harriet Alder/JC