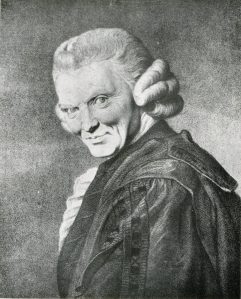

In 1941, Kingsman Judge Edwin Max Konstam C.B.E. donated to the College a collection of books and papers from the library of his late sister, the acclaimed actress Gertrude Kingston (1862–1937).

Kingston (born Gertrude Angela Kohnstamm) had many strings to her bow. Passionate about art from an early age, she studied painting in Paris and Berlin, going on to publish three illustrated books. She developed an interest in lacquer work and exhibited her creations in this medium in New York in 1927. She was a popular public speaker, using this talent initially on behalf of the women’s suffrage movement, and later in life also for the Conservative Party. She taught public speaking to others, and wrote many journalistic articles.

However, it was as an actress that Kingston was best known. Her acting career moved from amateur involvement as a child to professional work after her marriage in 1889, necessitated by deficiencies in her husband’s income. Adopting Kingston as her stage name, she made a reputation for herself on the London stage, acting in Shakespearean and classical as well as contemporary roles. One of the most notable of these roles was as Helen of Troy in Euripides’ The Trojan Women. Kingston undertook this role at the suggestion of playwright George Bernard Shaw (1856–1950).

Kingston appeared in a number of productions of Shaw’s plays, and seems to have been highly regarded by him. The pair were in regular correspondence, as the large number of letters from Shaw to Kingston amongst the papers given to the College by her brother testify. Kingston also owned several copies of early published editions of Shaw’s plays, some of which are likely to have been her working copies, since they contain performance annotations.

One of the earliest of Shaw’s plays in Kingston’s collection is a first edition of Press Cuttings dating from 1909. This play is a satire of the anti-suffragist lobby, so is likely to have appealed to her feminist sensibilities. The cover has a label proclaiming “Votes for women”:

Cover of the first edition of George Bernard Shaw’s play Press cuttings London, 1909. Shelfmark N.28.5

The title character of Shaw’s play Great Catherine was written specifically for Kingston, and in November 1913 she duly starred in its first production at the Vaudeville Theatre in London.

Note detailing the cast of the first performance of Great Catherine in 1913, with Gertrude Kingston in the starring role. From the flyleaf of Great Catherine, London, 1914. Shelfmark N.28.4

Shaw’s inscription on the half-title page of Kingston’s copy of Heartbreak House, Great Catherine, and playlets of the war identifies her closely with the lead role and underlines the high regard he had for her:

Half-title page of Heartbreak House, Great Catherine and playlets of the war, London, 1919. Shelfmark N.28.2. Shaw’s inscription reads: “To Gertrude Kingston, Catherine the second, but also Catherine the first (and the rest nowhere) from Bernard Shaw. 10th Oct 1919”

Kingston’s personal copy of Great Catherine is an early unpublished rough proof:

This is one of the volumes containing pencil annotations within the text, likely to have been made by Kingston in order to help guide her performance:

In 1921 Gertrude Kingston joined the British Rhine Army Dramatic Company in Germany. She reprised the role of Lady Waynflete in Shaw’s 1901 play Captain Brassbound’s Conversion, having first played this character in 1912. The front cover of Kingston’s copy of this play gives instructions in several languages on where it should be returned if she should happen to misplace it:

Tucked inside the play is a leaflet advertising this production and other forthcoming “Army amusements” at other theatres:

Collections such as these provide a fascinating glimpse into a long-vanished theatrical world.

AC

References

Kate Steedman, “Kingston, Gertrude [real name Gertrude Angela Kohnstamm] (1862–1937), actress.” Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. 23 Sep. 2004; Accessed 16 Apr. 2020.