As the 400th anniversary year of Shakespeare’s First Folio reaches Halloween and the nights draw ever inward, our focus shifts to some of the spookier elements in Shakespeare’s plays, and particularly the witches and ghosts to be found in Macbeth. In addition, as we proceed, other witches and eerie creatures may swoop in from elsewhere in the Library’s collections.

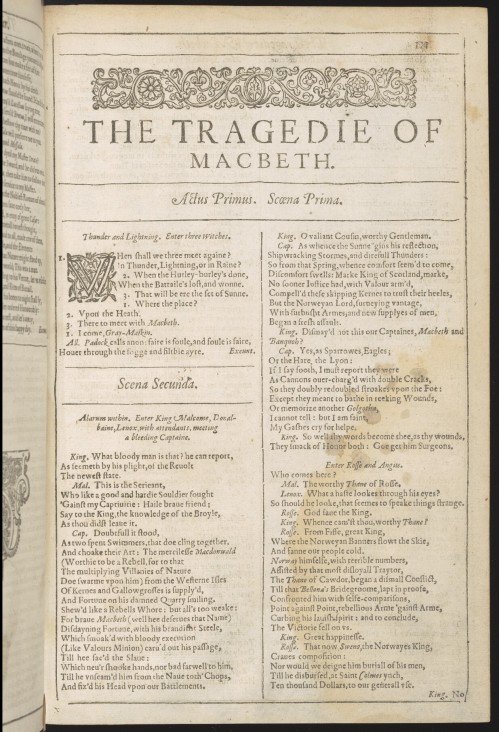

Macbeth, believed to have been first performed in 1606, appears in print for the first time in the First Folio in 1623. It is thought that the Folio text was drawn from the latest version in theatres at the time, which incorporated revisions by the playwright Thomas Middleton (1580-1627). One of Middleton’s revisions is thought to be the addition of two songs for scenes featuring the witches: “Come away, come away” and “Black spirits and white”. These songs are only mentioned by title in the Folio, but appear, complete with full lyrics, in Middleton’s own play The Witch (ca. 1613-1616). This expansion of the role of the witches reflected the continuing fascination of Jacobean audiences with witchcraft. This fascination was born partly out of the obsessions of King James I, whose book Dæmonologie was first published in 1597, and was then reprinted when he ascended the throne of England in 1603. James, who was convinced that he had almost met his death via witch-conjured storms in the North Sea, argued in his book that witchcraft arose from demons and humans working together to spread misery and destruction. Shakespeare is thought to have used Dæmonologie as one of his chief sources and inspirations in creating the play in the first place, likely with an eye on the King’s favour. The plot’s focus on the murder of a King and its aftermath is also believed to reflect elements of the Gunpowder plot of 1605.

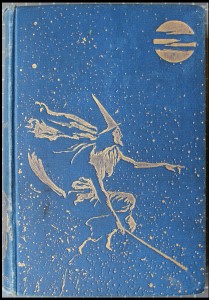

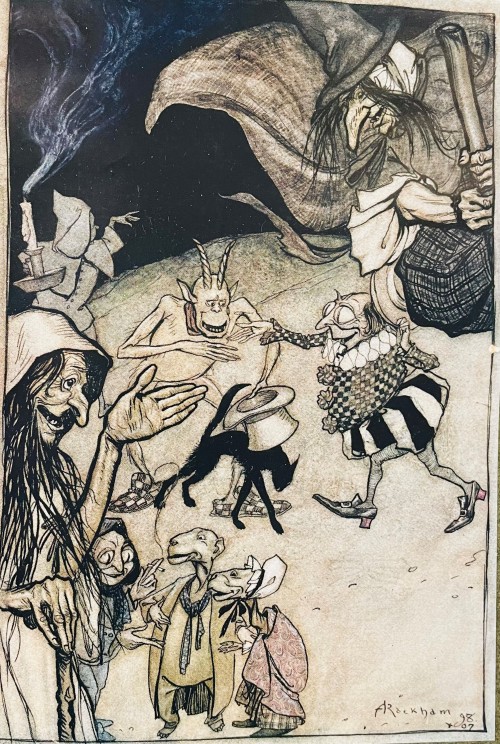

Frontispiece of The Ingoldsby Legends, by Thomas Ingoldsby; illustrated by Arthur Rackham, London, 1907 (YHK BARH ZIN)

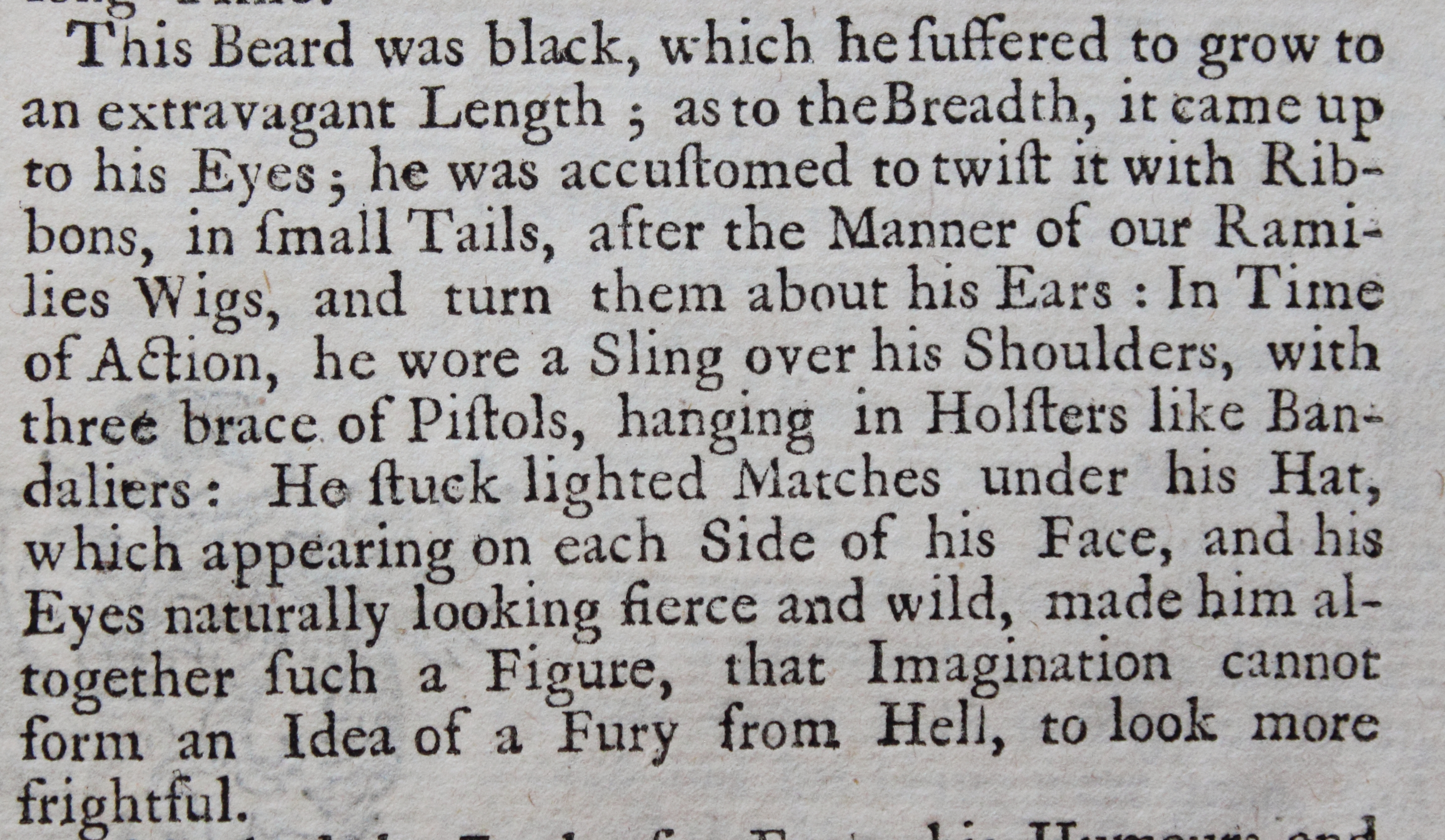

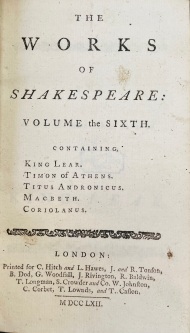

Next we turn to two eighteenth-century editions of the dramatic works of Shakespeare. The first, part of the Keynes Bequest, was edited by Lewis Theobald (ca. 1688-1744), who is a significant figure in Shakespeare scholarship. Theobald worked hard to correct errors and alterations that had crept into the plays through the work of earlier eighteenth-century editors, and surveyed as many surviving copies of the plays as he could in order to produce the most authoritative versions possible. His edition, originally published in 1733, was drawn upon heavily by subsequent major editors such as Edmund Malone (1741-1812), and thus continues to inform modern editions of the plays. Our set of Theobald’s Shakespeare dates from 1762. Macbeth appears in volume six, accompanied by an engraving by Hubert-François Gravelot (1699-1773), which depicts Macbeth confronting Banquo’s ghost during the feast scene (Act 3, scene 4).

Title page of volume six of The works of Shakespeare, [edited] by Mr Theobald, London, 1762 (Keynes.P.13.24)

First page of Macbeth from The works of Shakespeare, [edited] by Mr Theobald, London, 1762 (Keynes.P.13.24)

The second eighteenth-century edition is, like the First Folio, part of the Thackeray Collection. This fifteen-volume set, which dates from 1793, is an expanded version of an eight-volume edition of Shakespeare’s plays which originally appeared in 1765, and which was co-edited by the eminent writer Samuel Johnson (1709-1784). Johnson had an abiding love of Shakespeare and had long wished to produce his own edition of the plays. He tested the waters in 1745 with the publication of his Miscellaneous Observations on the Tragedy of Macbeth, then spent the next twenty years working towards his goal. The preface to Macbeth in the 1793 edition includes Johnson’s ruminations on the supernatural themes of the play. He states:

A poet who should now make the whole action of his tragedy depend upon enchantment, and produce the chief events by the assistance of supernatural agents, would be censured as transgressing the bounds of probability … and condemned to write fairy tales instead of tragedies; but a survey of the notions that prevailed at the time when this play was written, will prove that Shakspeare [sic] was in no danger of such censures, since he only turned the system that was then universally admitted, to his advantage, and was far from overburdening the credulity of his audience.

Speaking of the prevailing atmosphere of the late 15th and early 16th centuries, he writes evocatively:

The Reformation did not immediately arrive at its meridian, and though day was gradually increasing upon us, the goblins of witchcraft still continued to hover in the twilight.

Having touched upon on James I’s preoccupation with witchcraft and its effect on the population, he goes on to say:

Thus the doctrine of witchcraft was very powerfully inculeated [sic]; and as the greatest part of mankind have no other reason for their opinions than that they are in fashion, it cannot be doubted but this persuasion made a rapid progress, since vanity and credulity co-operated in its favour.

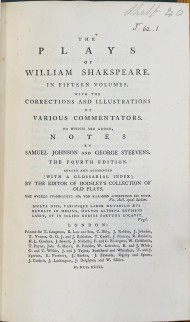

Title page of The Plays of William Shakspeare, edited by Samuel Johnson and George Steevens, London, 1793 (Thackeray.J.62.1)

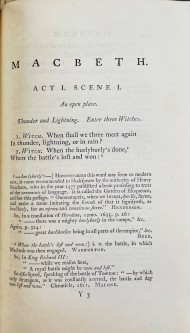

First page of Macbeth from volume 7 of The Plays of William Shakspeare, edited by Samuel Johnson and George Steevens, London, 1793 (Thackeray.J.62.7)

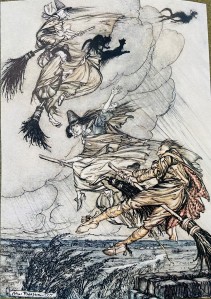

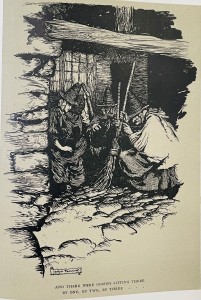

Three witches from a story called “The witches’ frolic”. Plate facing page 106 of The Ingoldsby Legends

In 1807, Charles Lamb (1775-1834) and his sister Mary (1764-1847) produced a prose version of some of Shakespeare’s plays, modified to be suitable for children. More adult elements and complicated subplots were removed, but care was taken to adhere to the spirit of the originals, and to keep as much of the language as they could. The Library has a copy of the sixth edition, dating from 1838, which is the first edition to credit Mary Lamb on the title page. Macbeth appears in this volume, and the witches are described as follows:

… three figures like women, except that they had beards, and their withered skins and wild attire made them look not like any earthly creatures.

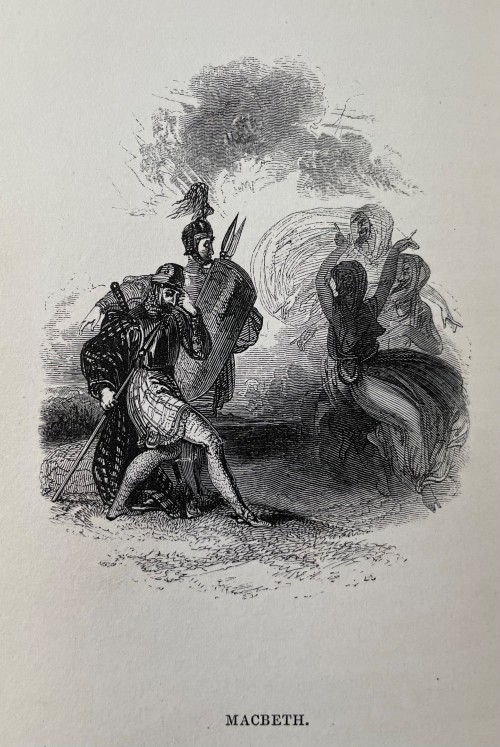

An illustration, pictured below, accompanies the tale, showing Macbeth and Banquo encountering these strange beings.

Engraving of Macbeth and Banquo encountering the three witches. Plate from Tales from Shakspeare, by Mr and Miss Lamb, London, 1838 (YHK LAM X 4)

We leave you with a final dose of the supernatural via another wonderful illustration by Arthur Rackham (1867-1939) from The Ingoldsby Legends. Originally serialised in the 1830s, the legends comprised ghost stories, myths and poems written by clergyman Richard Harris Barham (1788-1845) under the pen-name Thomas Ingoldsby. They were later published in book form and were hugely popular for decades. An edition featuring Rackham’s glorious illustrations was first published in 1898.

Stay safe and watch out for whatever might be lurking out there in the dark this Halloween!

References

Julian Goodare, A royal obsession with black magic started Europe’s most brutal witch hunts [accessed 10/10/23]

Emma Smith, The Making of Shakespeare’s First Folio, Oxford, 2015

You can browse King’s College’s First Folio on the Cambridge University Digital Library here and it also features on the First Folios Compared website where you can compare it side by side with other digitised copies of the First Folio.

AC