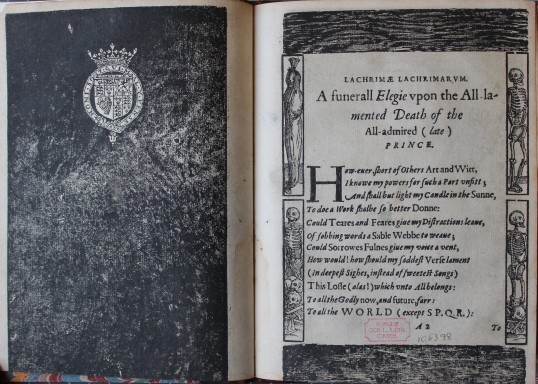

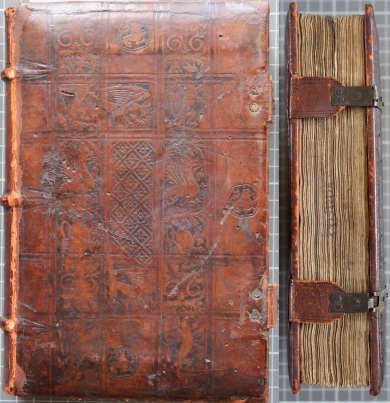

The untimely death of Henry Frederick, Prince of Wales was met with universal sorrow across the land in 1612. The national outpouring of grief is probably comparable to that witnessed in the aftermath of Princess Diana’s death in 1997. Prince Henry (1594-1612), the eldest son of James I and brother of the future King Charles I, was praised in life by authors including George Chapman, Sir John Davies, Michael Drayton, and Francis Bacon. There was a proliferation of mourning pamphlets and funeral sermons following the popular Prince’s death at the age of 18 from typhoid fever, and he was mourned by such luminaries as Thomas Campion, George Herbert, and Sir Walter Raleigh. Prince Henry was the patron of the poet Josuah Sylvester (1563-1618), who expressed his sorrow in Lachrimae lachrimarum (1612), one of the earliest examples of a book containing black mourning pages:

The tears of tears: title page of the first edition of Lachrimae lachrimarum; or, The distillation of teares shede for the untymely death of the incomparable Prince Panaretus (London: Humfrey Lownes, 1612; Keynes.C.12.8).

The sense of grief is compounded by a black page with a woodcut of the royal arms on every verso, and mourning borders with skeleton frames on each recto:

The first edition includes elegies in English, French, Latin and Italian by the royal tutor, Walter Quin (1575?-1640):

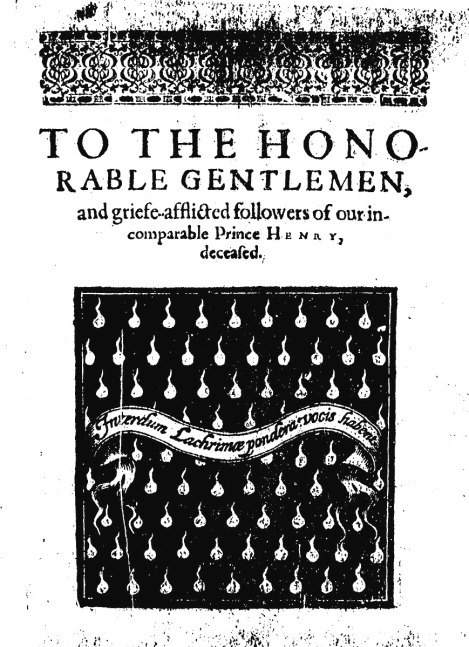

While tears are only mentioned in Sylvester’s book, these are shown explicitly in Christopher Brooke’s Two Elegies (1613), which features a pattern of tears with a quotation from Ovid’s Epistulae ex Ponto, 3.1.158: “Interdum lachrimae pondera vocis habent” (sometimes tears have the same weight as words):

Christopher Brooke, Two elegies, consecrated to the neuer-dying memorie of the most worthily admyred; most hartily loued; and generally bewayled prince; Henry Prince of Wales (London: Thomas Snodham, 1613; image from EEBO).

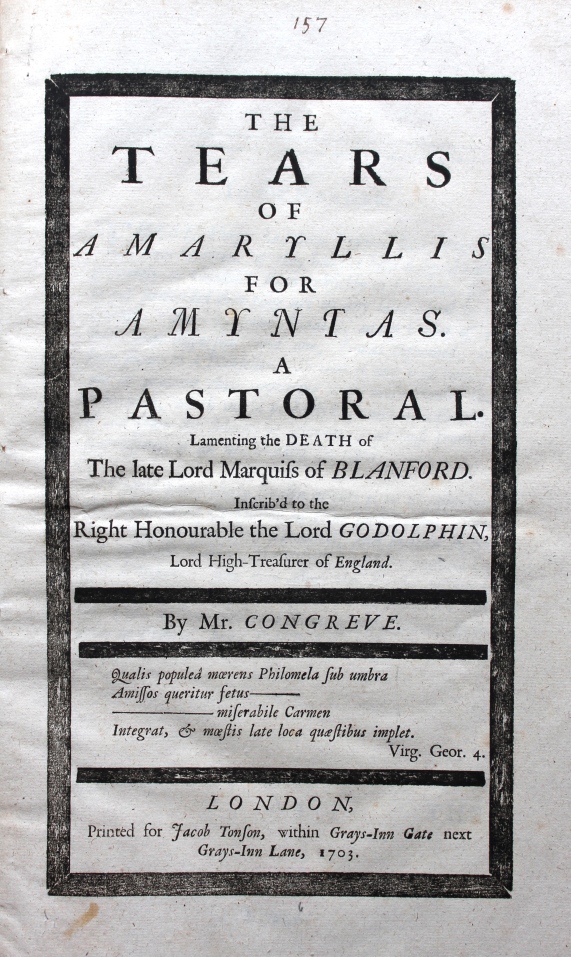

Variations on the black mourning page were used widely well into the 18th century. The premature death of John Churchill, Marquess of Blandford (1686-1703), who died here at King’s College on 20 February 1703, was lamented in William Congreve’s The Tears of Amaryllis for Amyntas (1703). The title page is framed within a mourning border of black blocks:

Title page of William Congreve’s The Tears of Amaryllis for Amyntas (London: Jacob Tonson, 1703; Keynes.C.5.6).

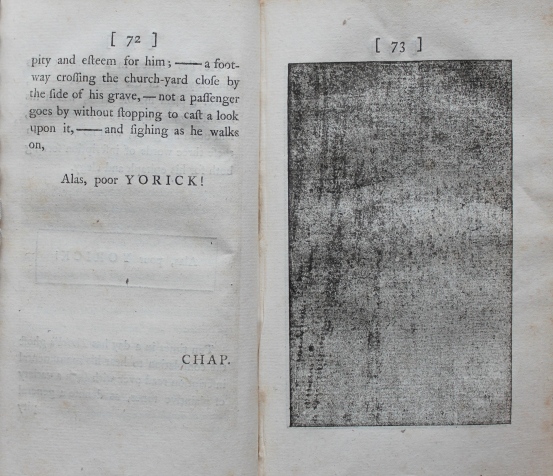

The black mourning page may be a technique that originated in the 17th century, but one of the most well-known examples of this practice is to be found in the 18th century, namely in Laurence Sterne’s novel Tristram Shandy (1759-67), which is revolutionary in its use of unconventional typographical devices such as blank and marbled pages. Yorick’s death in vol. 1 is followed by a black mourning page:

Alas, poor Yorick: black mourning page in the first edition of Sterne’s The Life and Opinions of Tristram Shandy, Gentleman (York: J. Hinxman, 1759; Keynes.Ec.7.1.15).

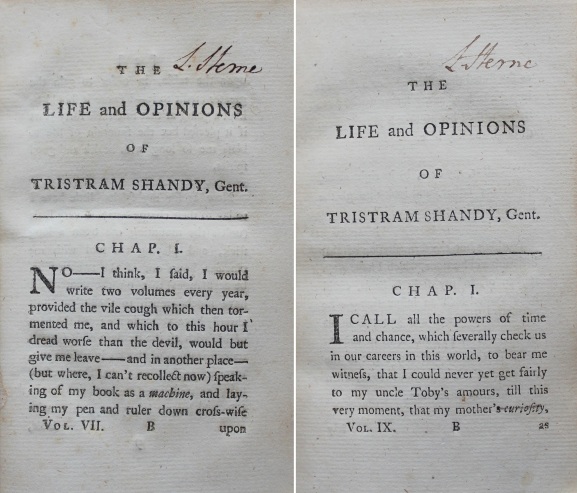

In order to protect his work from piracy, Sterne signed the opening chapter of the first and second editions of volume 5, as well as the first editions of volumes 7 and 9. He must have therefore autographed over 12,000 volumes:

Opening chapters of volumes 7 and 9 of Tristram Shandy, with Sterne’s autograph (Keynes.Ec.7.1.21 and Keynes.Ec.7.1.23).

Today is Blue Monday, allegedly the gloomiest day of the year, so we thought this would cheer everyone up. And let’s look on the bright side: if Prince Henry had lived to become King, he would have probably been beheaded during the English Civil War, as happened to his younger brother Charles I, so it looks like he had a lucky escape after all…

IJ