As we are all surrounded by illuminations at this time of the year (whether we like it or not), let’s have a look at another type of illumination, that of the vibrant colours and intricate decorations of initials and margins often found in medieval manuscript books. Such illuminations were also a feature of early printed books and can be regarded as a vestige of the manuscript tradition that persisted in the transition to the printing era. As Scrase and Croft point out in their book Maynard Keynes, “It is characteristic of the earliest period of printing that the book was conceived as a collaboration between the practitioners of the new art and the professional scribes and illuminators whose traditional involvement in book production went back for centuries” (Cambridge: Provost and Scholars of King’s College, Cambridge, 1983, p. 74). The illuminations were applied by hand following completion of the printing process, and the printer would leave blank spaces with or without guide letters for the illuminator:

Diogenes Laertius, Vitae et sententiae eorum qui in philosophia probati fuerunt (Venice: Nicolas Jenson, 1475; Keynes.Ec.7.2.9).

This 1476 copy of Boethius’s De consolatione philosophiae has the first initial of text illuminated in gold and blue, with a pink, green and blue decorative leaf border carried around the inner and lower margins:

Boethius, De consolatione philosophiae (Nuremberg: Anton Koberger, 1476; Keynes.Ec.7.1.4) with close-up of initial illuminated in gold and blue.

Sometimes, the initial letters were simply supplied in red, blue or gold, as in this copy of Lucian’s Opera (1503):

One of the most impressive illuminations in the incunabula in the Keynes Bequest is undoubtedly to be found in a copy of Saint Augustine’s De civitate Dei (1468), printed in Rome by two Germans, Konrad Sweynheim and Arnold Pannartz, who are credited with introducing the art of printing into Italy. The first page of text after the preliminaries features the initials “I” and “G” supplied in gold; both initials are embellished with a decorative white vine stem border defined in blue, pink and green with a pattern of white dots, which extends into the upper, inner and lower margins. In the lower margin is a painted coat of arms of Cardinal Medici within a green laurel wreath and a putto on either side:

Saint Augustine, De civitate Dei (Rome: Konrad Sweynheim and Arnold Pannartz, 1468; Keynes.Ec.7.1.2). The Medici arms are not authentic and were added by the forger Hagué.

Below is a close-up of the 15-line initial “I” and the 8-line initial “G”:

Saint Augustine, De civitate Dei (Rome: Konrad Sweynheim and Arnold Pannartz, 1468; Keynes.Ec.7.1.2); detail.

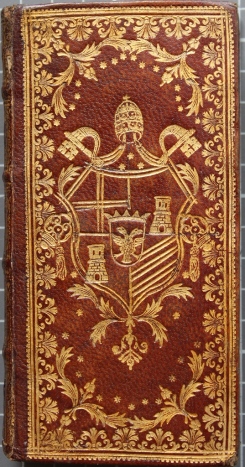

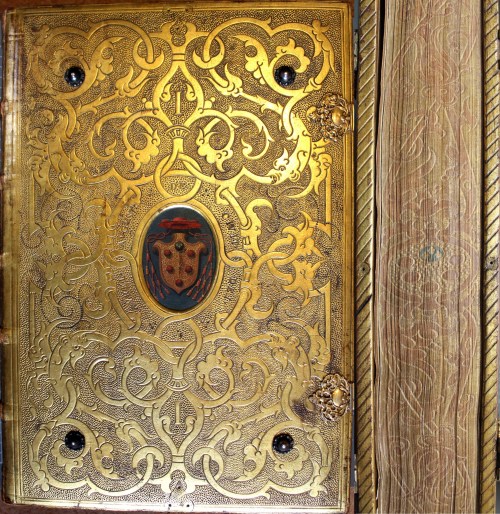

If you thought the illumination in this incunabulum was impressive, wait until you see the cover. This is a 19th-century binding entirely covered in gold produced by the Belgian bookbinder and binding forger Théodore (aka Louis) Hagué (1822 or 1823-1891) in imitation of a 16th-century Italian binding purported to have been made for Cardinal Medici:

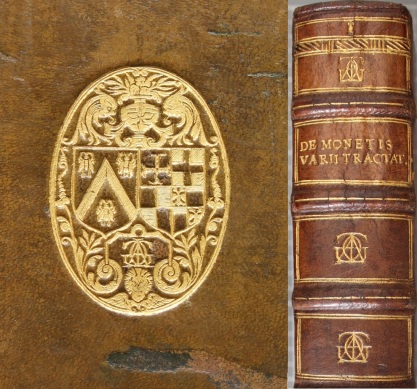

The book with the golden cover: calf over wooden boards; covers and spine entirely covered in gold with an elaborate interlacing ribbon/strapwork design; four metal bosses on each cover; arms of Cardinal Medici painted in an oval medallion at the centre of each cover. Detail shows gilt and gauffered edges with the Medici coat of arms in the middle, and the pattern of the decorations filled in with red.

Hagué was a master of forgery and produced fake bindings that were passed off as having belonged to popes, cardinals, kings and queens. And people fell for it hook line and sinker. The sale catalogue description pasted on the fly-leaf reads: “Italian binding of the 16th century. This book is probably unique in its style of binding. It is of calf; tooled and completely covered with gilding. On each cover the arms of Cardinal Medici are painted…” For more information on Hagué, see Mirjam M. Foot, “Binder, Faker and Artist”, The Library 13.2 (2012), pp. 133-146, available here.

This is our last blog post before Christmas, so happy festive season from all of us at King’s College Library and Archives! We’ll be back in the New Year with more posts about the treasures in our special collections, so watch this space…

IJ