According to the OED, the etymology of the verb “to bowdlerize”, meaning “to expurgate (a book or writing), by omitting or modifying words or passages considered indelicate or offensive”, comes from Thomas Bowdler (1754-1825), “who in 1818 published an edition of Shakespeare, ‘in which those words and expressions are omitted which cannot with propriety be read aloud in a family’”.

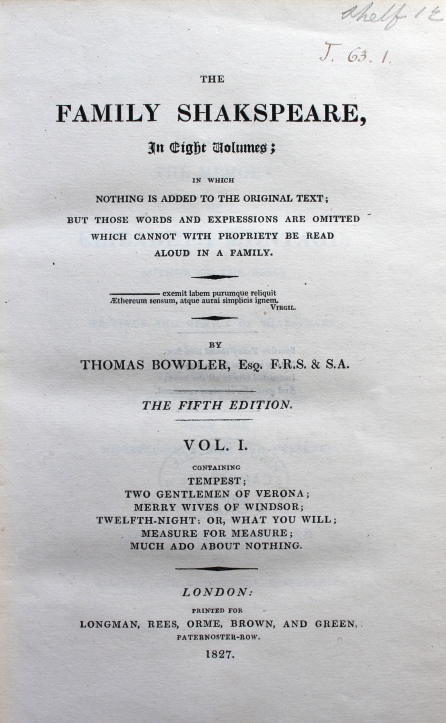

In the collection of books bequeathed to King’s College by its sometime Provost George Thackeray (1777-1850), a cousin of the novelist William Makepeace Thackeray, is a copy of the fifth edition of Thomas Bowdler’s eight-volume The Family Shakspeare (1827):

Title of page of vol. 1 of Thomas Bowdler’s The Family Shakspeare (London: Printed for Longman, Rees, Orme, Brown, and Green, Paternoster-Row, 1827) Thackeray.J.63.1

Some of the alterations to Shakespeare’s plays made by Bowdler include, for example, Lady Macbeth’s line, “Out, damned spot!” changed to “Out, crimson spot!” (Macbeth, V.1); in Henry IV, Part 2 the prostitute Doll Tearsheet is omitted from the story altogether; and in all plays the exclamation “God!” is replaced with “Heavens!”

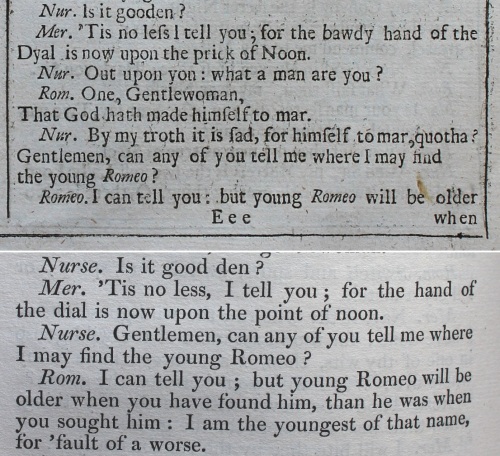

Below is the scan of a line spoken by Mercutio in Romeo and Juliet (II.iv) as it appeared in the Fourth Folio of Shakespeare’s plays (1685) along with the expurgated version printed by Bowdler (vol. 8, p. 168):

Spot the difference: Mercutio’s “the bawdy hand of the dial is now upon the prick of noon” has been changed to “the hand of the dial is now upon the point of noon”.

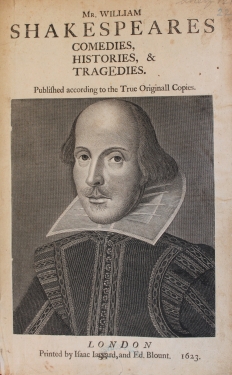

Thackeray’s obituarist writes that “In his discipline generally there was something of almost Roman firmness … Yet under the rigid manner lay the kindest sympathy”. While his library included the First, Second and Fourth Folios of Shakespeare’s plays – as well as later editions – it is interesting that this is the edition he decided to present to his daughter, who recorded the gift on the fly-leaf of all eight volumes: “Mary Ann Eliz.th Thackeray the gift of her father”. But this is perhaps more a reflection on the times than on Thackeray himself.

All these books, along with many other treasures, will be on display at King’s Library’s free Shakespeare exhibition as part of Open Cambridge on Friday 9th and Saturday 10th September, 10.30am – 4pm:

http://www.opencambridge.cam.ac.uk/news/kings-college-library-and-archives-open-their-doors

We hope to see many of you there!

IJ