Whether it be College catering, or spicy titbits from our rare books and early printed music, there is a feast of food-related material in the King’s College special collections. We table here an exhibition of serious, as well as fun, documents covering five hundred years of food at King’s. From food fights to food scarcity, the salutary effect of warm beer, or the economics of the price of corn, the special collections are sure to have something to satisfy any appetite!

the price of wheat

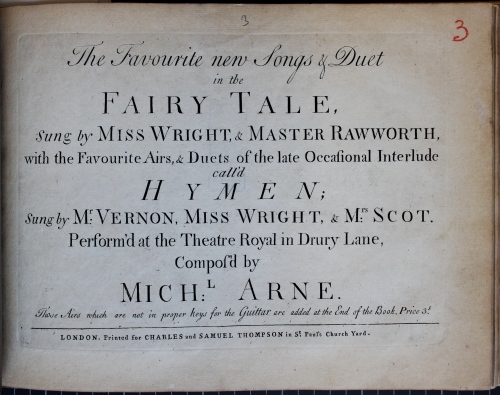

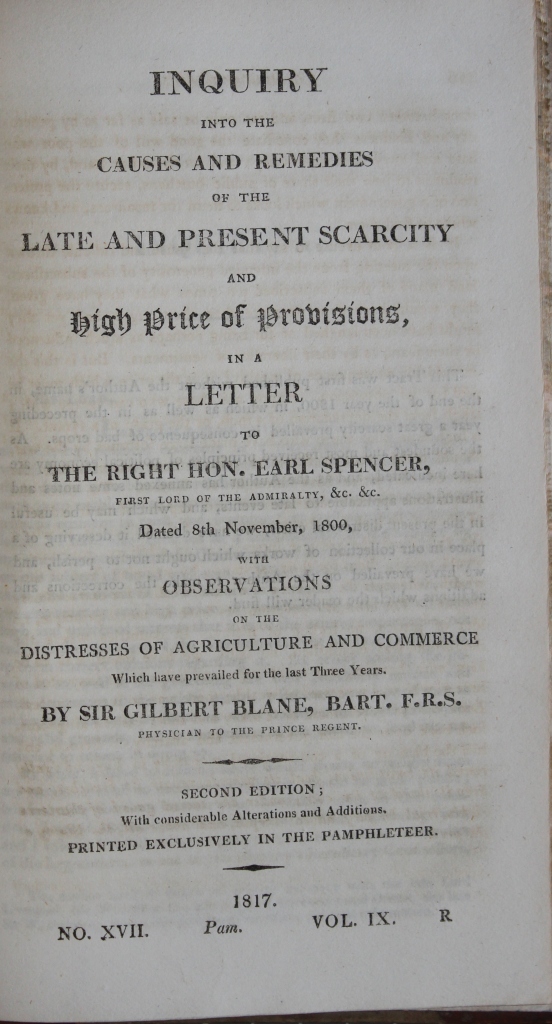

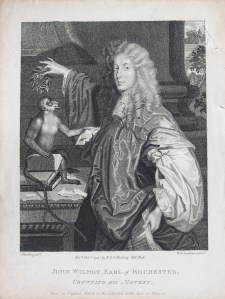

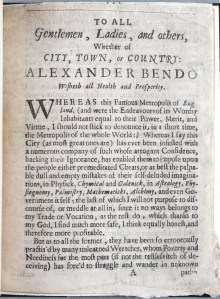

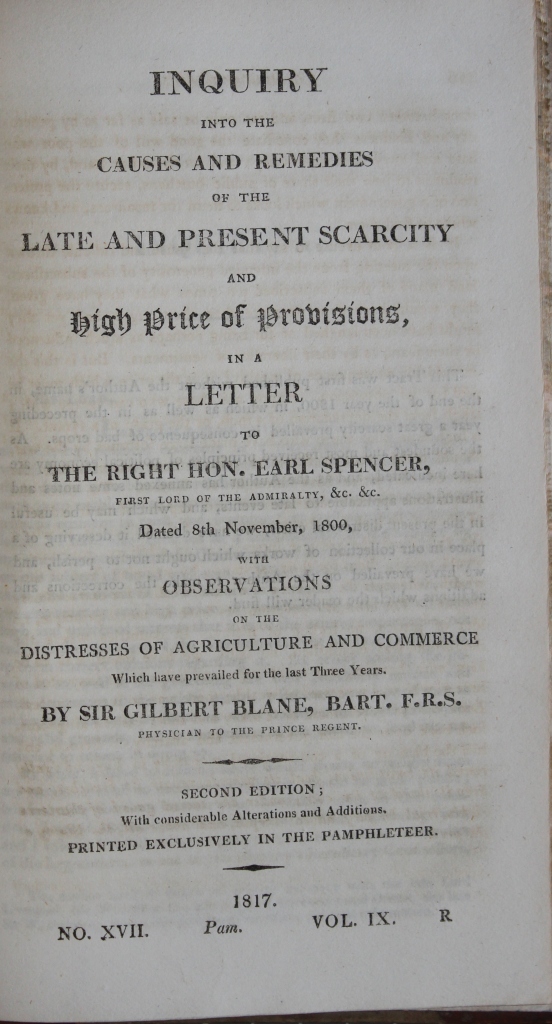

During the years between 1799 and 1801 widespread rioting broke out throughout England, mostly about the scarcity of food and soaring prices of bread. The cost of a loaf of bread was at an all-time high of 1 shilling and 9 pence. This was caused in part by a series of poor harvests as a result of unseasonally bad weather in England and equally poor harvests in Europe which limited imports. Sir Gilbert Blane (1749–1834) deals with the causes and remedies in his inquiry in 1800. Trained as a physician, we can perhaps be forgiven a wry (or even rye?) smile when we learn that Blane had previously been the personal physician to Admiral Sir George Rodney (1718–1792) on board HMS Sandwich!

Gilbert Blane, Inquiry into the causes and remedies of the late and present scarcity and high price of provisions (London, 1817) (Shelfmark: Keynes.A.10.16.(10.)). Title page

Blane, Inquiry into the causes and remedies of the late and present scarcity and high price of provisions. Summary

That particular volume came to King’s as part of the antiquarian book collection bequeathed by John Maynard Keynes. He was First Bursar (Financial Officer) at King’s from 1924 to 1944, and converted our land-based endowment to a stock portfolio. His predecessor bursars had to maximise the income from our land holdings, and compiled tables of the prices of wheat and malt during the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries.

‘Prices of Malt clear of the Excise Duty with the Mean Prices’, January 1782-October 1806 (Ref: KCE/1060)

‘Prices of Wheat with the Mean Prices’, January 1782-October 1806 (Ref: KCE/1060)

The price of wheat per quarter (1/4 of a ton) ranged from just under 1 pound per quarter in the early eighteenth century, to well over 5 pounds in January 1796, and was in the 7-8 pounds per quarter range in the winter and spring of 1800-1801. The 1799–1801 scarcity came at the end of a decade of bad harvests and hard winters—the problem was not so much that the rioters were fed up, as that they were not fed up!

Charles Simeon. Etching by an unknown artist (undated) (Ref: KCAC/1/4/Simeon/2)

King’s did what it could towards poor relief. During the 1788 famine Charles Simeon (1759–1836, KC 1779) ‘organized a [University] subscription to enable bread to be sold at half-price in Cambridge and twenty-four neighbouring villages and rode round on horseback each Monday to make sure that the bakers were doing this.'[ODNB] In 1795 King’s College fellows were again occupied with poor relief. It was ‘agreed that ten guineas be given between the parishes of Grantchester Coton and Barton to be distributed at the discretion of Mr Simeon.’

Governing Body minutes, 16 January 1795 (Ref: KCGB/4/1/1/2)

We are not exempt from scarcity even in modern times. During World War II the College accommodated some of the Dunkirk evacuees, followed by an RAF transport unit, a quantity of relocated Queen Mary’s College students and faculty, and a miscellany of American and British military men in various stages of training. The acting bursar GHW ‘Dadie’ Rylands had to deal with the problems of rationing: an allowance of only half a sausage per head per week!

Part of a letter from the Acting Bursar to Sainsbury’s, about rationed meat (carbon copy), 14 November 1941 (Ref: KCAR/3/1/1/11)

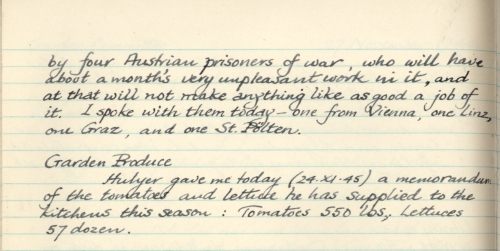

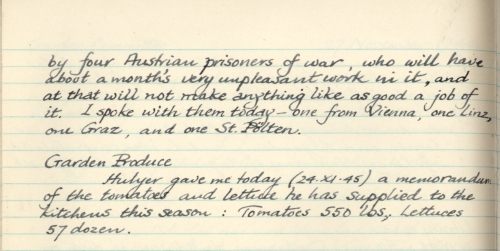

Luckily for King’s we had enough space for a kitchen garden. Despite reduced staff, in 1941 the head gardener ‘produced large quantities of tomatoes, lettuces, onions, and savoys for use in Hall. ‘ In 1945 he supplied 550 pounds of tomatoes and 57 dozen lettuces.

Entry from George Salt’s college gardens journal, 1941 (Ref: GS/2/5 p 75)

Entry from George Salt’s college gardens journal, 1945 (Ref: GS/2/5 page 92)

what they ate

Go back a couple of centuries before the wheat shortage, however, and according to Robert Speed’s The Counter Scuffle (1621) there was plenty of food to waste! This publication was one of the most influential mock poems of the time and went through 19 editions by the end of the seventeenth century. It tells the story of a food fight which broke out during a Lent dinner in the Wood Street Counter, a debtors’ prison. At the end of the fight, the prison keeper is found hiding under a table with his clothes and codpiece stuffed with food!

Robert Speed, The Counter Scuffle (London, 1648). (Shelfmark: Thackeray.J.65.48). Title page

Speed, The Counter Scuffle. Part of the description of the food

Speed, The Counter Scuffle. Part of the description of the fight

The foodstuffs being thrown around the prison dining hall are the same as King’s fellows and scholars were eating about 40 years earlier. The College’s dining accounts for 16-19 October 1579 list various types of fish (ling, plaice, tench, and pickerel–but no eels or herring), mutton and loin of veal, and the ‘flesh’ included beef, rabbits, pigeons, and chickens. The College also purchased milk, butter, eggs, pepper, sugar, currants, dates, cinnamon, cloves and mace during those days. Other pages in the accounts record the purchase of mustard. (See The Potticaries Bill blog and an article about early dining practices at King’s for more details).

College dining accounts for 16–19 October 1579 (Ref: KCAR/4/1/6/19 opening 276)

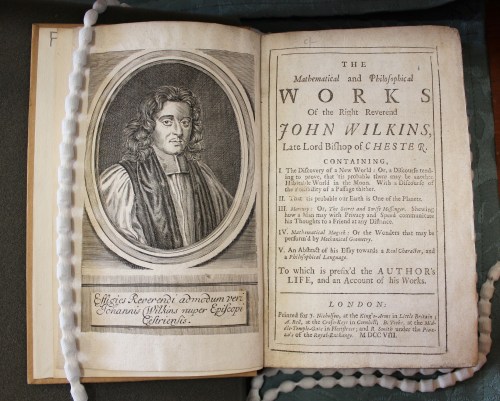

One would never catch Oxbridge dons engaging in such puerile behaviour as displayed in The Counter Scuffle, however. Why play or fight with your food when you can be academic about it? It is hard to imagine that the humble sausage would inspire a volume of poetry, but that is exactly what happened when Thomas Warton (1728–1790), sometime Poet Laureate and friend of Dr Johnson, put together his volume of poetry The Oxford Sausage in 1764 whilst he was Professor of Poetry at the University of Oxford. Here we have his new edition ‘adorned with cuts, engraved in a new taste, and designed by the best masters.’ The volume’s engraved frontispiece depicts Mrs Dorothy Spreadbury, the inventress of the Oxford sausage. There is apparently some doubt about the authenticity of this claim, but who would be so bold as to challenge such a formidable-looking lady!

The Oxford sausage: or, Select poetical pieces, written by the most celebrated wits of the University of Oxford (Oxford, 1777) (Shelfmark: Chawner.A.5.105). Title page.

The Oxford sausage. Frontispiece showing Mrs Dorothy Spreadbury.

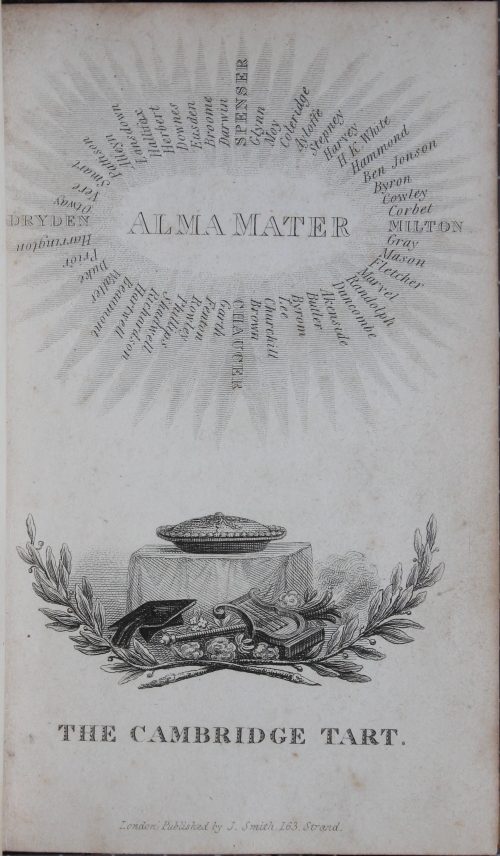

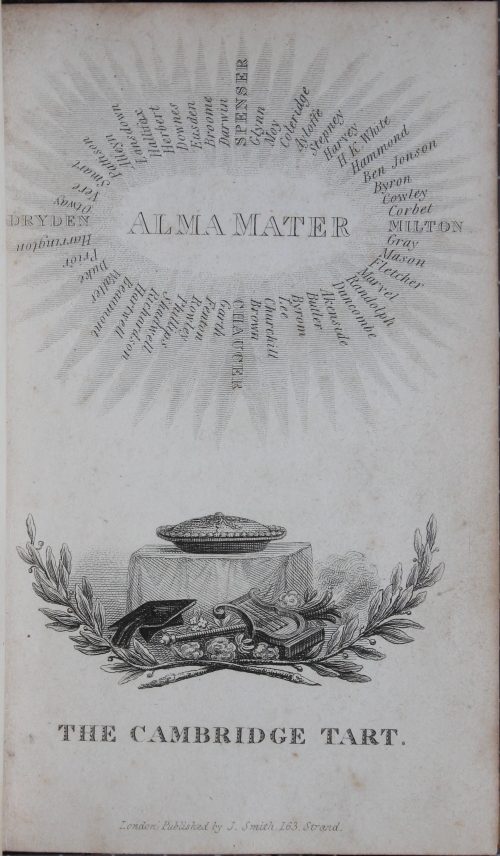

Over 50 years later in 1823 Cambridge decided it needed to acknowledge Oxford’s Sausage: ‘Oxford has its sausage, and why not Cambridge its tart?’ reads the preface to The Cambridge Tart, a volume of ‘epigrammatic and satiric-poetical effusions … dainty morsels, served up by Cantabs, on various occasions’ put together by Richard Gooch (1791–1849) in 1823 under the pseudonym ‘Socius’. The engraved frontispiece depicts a baked tart, framed by laurel wreaths, a lyre and a mortarboard!

The Cambridge tart: epigrammatic and satiric-poetical effusions; &c. &c. Dainty morsels, served up by Cantabs, on various occasions. Dedicated to the members of the University of Cambridge / By Socius (London, 1823) (Shelfmark: P.25.13). Title page

The Cambridge tart. Opening

The Cambridge tart. Opening

what they drank

Of course with your sausage you need something to drink, perhaps a nice chilled beer on a summer’s day? Even better, a nice warm beer, perhaps, as the writer of this little treatise explains to us the ‘many reasons that beere so qualified is farre more wholsome than that which is drunke cold’. It is a most serious subject indeed, with chapters that explain ‘that actuall hot drink doth quench the thirst as well as cold drink, or better’ and ‘the hurt that ariseth from the use of actuall cold drink’ and ‘the benefit that ariseth from the use of actuall hot drink’.

Warme beere, or, A treatise wherein is declared by many reasons that beere so qualified is farre more wholsome then that which is drunke cold (Cambridge, 1641) (Shelfmark: Thackeray.J.66.45). Title page

King’s had its own brewer, and brewery, for several hundred years. They brewed six barrels of ale at a time, and two of small beer.

College brewing numbers (undated) (Ref: KCAR/3/1/3/4 – memo on brewing)

John Pontifex (self-styled Coppersmith, Back-Maker, Brewer’s Millwright and Brewer’s Architect) sold us a six barrel brewer in 1829. It took three pages to describe it completely and it cost a shilling short of 213 pounds.

Part of an invoice for the brewing equipment purchased by King’s College from John Pontifex, 1829 (Ref: KCA/723)

Plan of the brewhouse of King’s College, by Richard Woods (undated) (Ref: KCD/365)

There was a fire in the brewhouse in 1871, and in 1881 the College voted to stop brewing its own beer. Two years later the brewhouse was converted to kitchen offices.

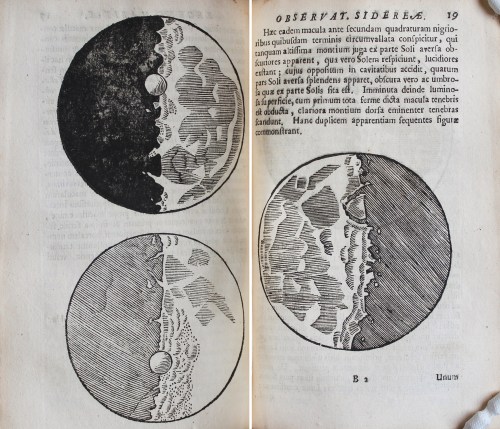

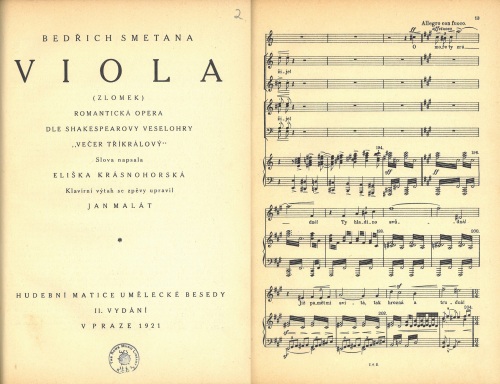

On the subject of brewing—hot drinks this time—we turn now to tea, coffee and chocolate. All were relatively new arrivals in Europe in the seventeenth century when Philippe Sylvestre Dufour (1622–1687) published his treatise De l’usage du caphé, du thé, et du chocolat. Here we have the latin translation of that work which appeared in Paris in 1685. It includes a separate treatise on each of the three drinks, under the title Tractatus novi de potu caphé; de Chinesium thé; et de chocolata. Each treatise includes a splendid engraved frontispiece depicting the origins of each drink. It is thought to be the first work in any language to describe all these new beverages in Europe.

Philippe Sylvestre Dufour, Tractatus novi de potu caphé; de Chinesium thé; et de chocolate (Paris, 1685) (Shelfmark: Thackeray.J.47.33). Title page

Dufour, Tractatus novi de potu caphé; de Chinesium thé; et de chocolate. Frontispiece

Dufour, Tractatus novi de potu caphé; de Chinesium thé; et de chocolate. Frontispiece to the chocolate treatise

Dufour, Tractatus novi de potu caphé; de Chinesium thé; et de chocolate. Frontispiece to the tea treatise

DRINKING SONGS

Would the King’s Dining Hall have ever resounded with drinking songs? Probably not, because the Founder’s statutes dictated that conversation in the Hall be conducted in Latin ‘unless a reasonable cause requires otherwise’, and always in a ‘modest and courtly’ fashion. Theological tracts were to be read at dinner, in good monastic style.

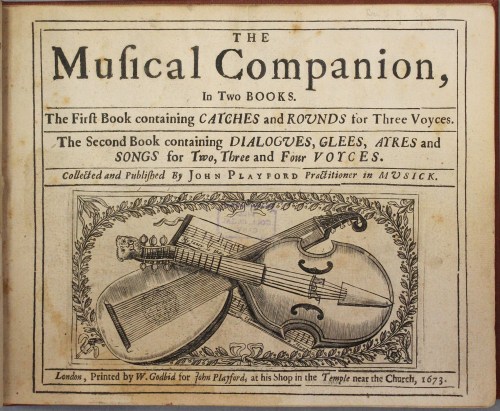

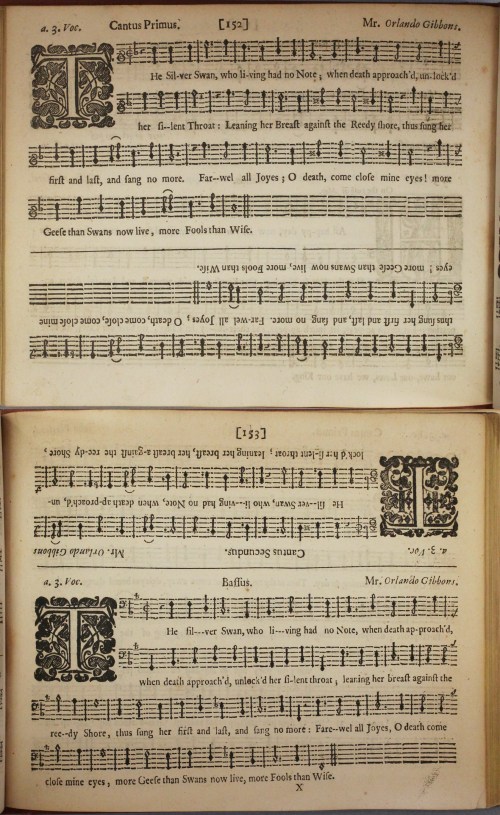

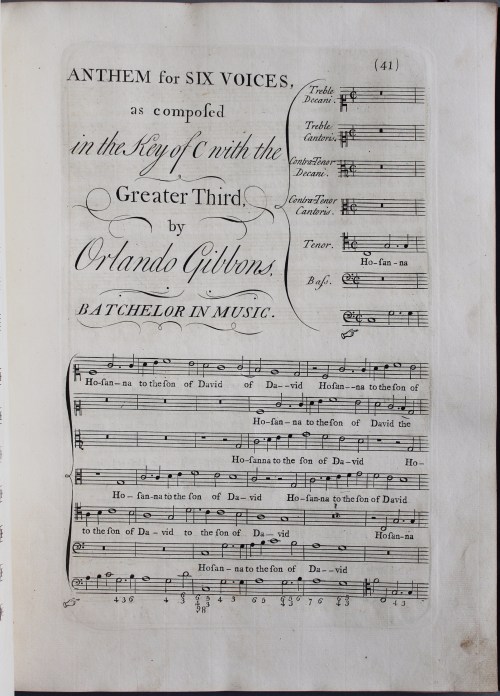

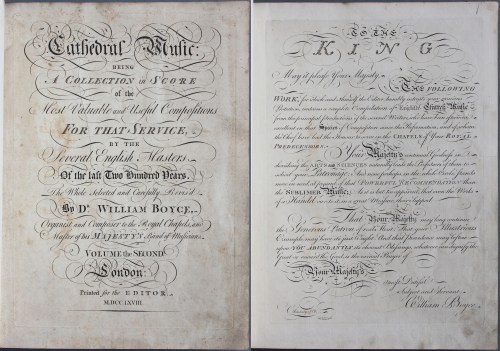

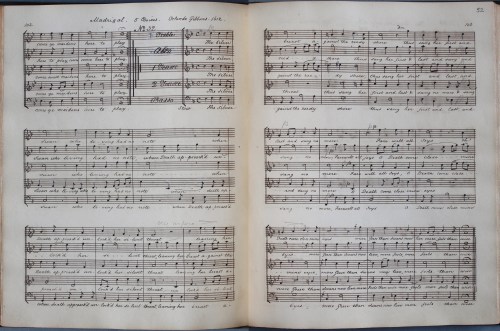

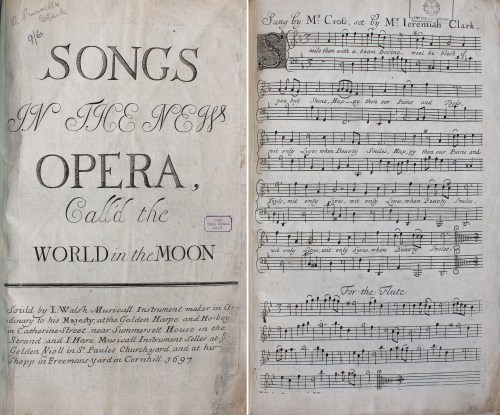

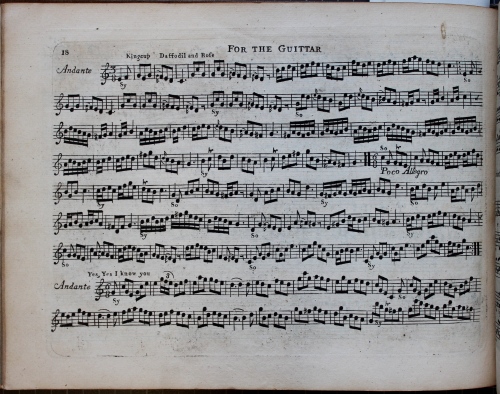

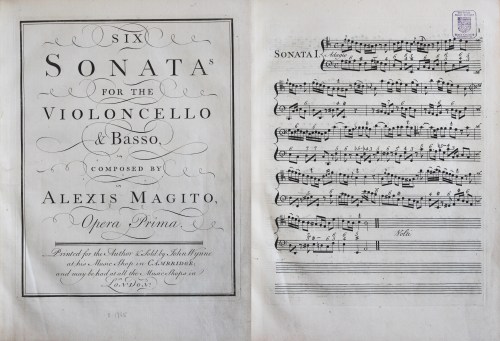

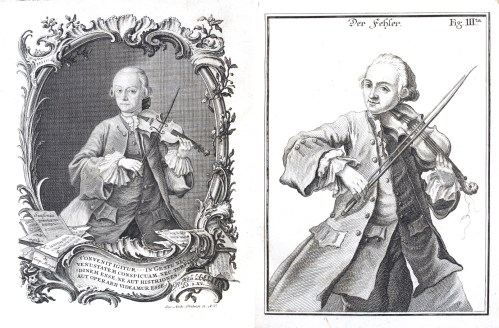

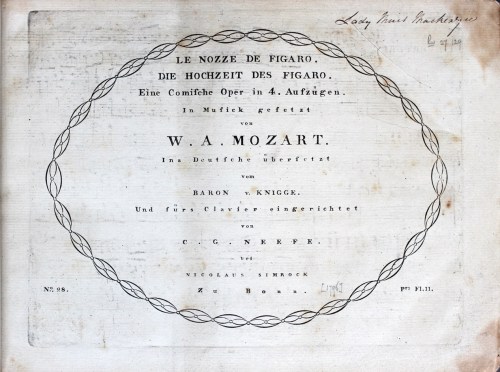

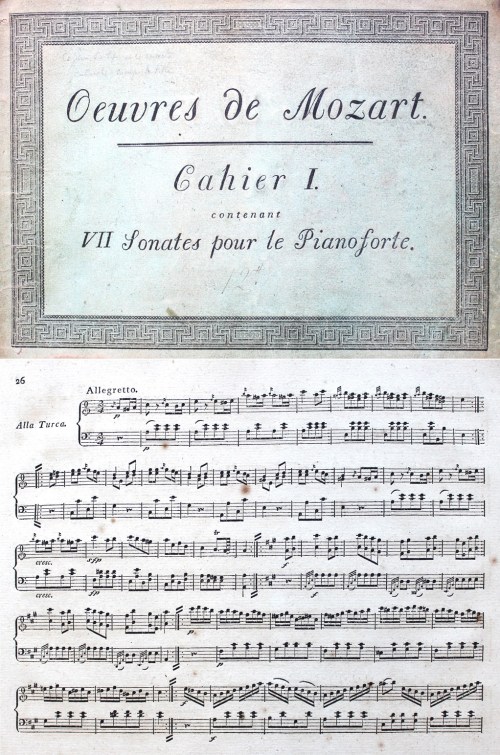

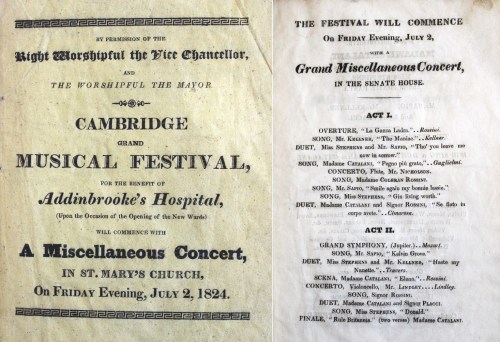

But such strictures don’t govern the College’s Rowe Music Library which has more than its fair share of music related to food and drink. In the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, one of the most common forms of popular song was the catch, a type of round. So-called catch and glee clubs sprang up in towns and cities, populated by men who liked to combine singing with feasting. While many catches of this period were bawdy in nature, at least as common was the subject of food and drink, with Henry Purcell, the greatest English composer of his generation, contributing to the repertoire such gems as ‘I gave her cakes and I gave her ale’, ‘He that drinks is immortal’ and ‘Wine in a morning makes us frolic and gay’. This catch in praise of punch is by Thomas Tudway (c. 1650–1726), organist of King’s College from 1670 until his death. The ‘S’ mark on the second stave shows the point at which the second voice should enter.

Thomas Tudway, ‘A Catch upon a Liquor call’d Punch’, in The Second Book of the Catch Club or Merry Companions (London, c. 1731) (Shelfmark: Rw.112.77)

The song sheet was ubiquitous in the early eighteenth century, with prints of love songs and operatic arias both available in abundance. This perhaps understandably anonymous song, ‘The Double Entendre’, appears at first sight to be about a maiden drinking a glass of wine, but each verse leaves open the possibility of a double meaning at the end of its third line, before things are resolved (after a pause and a playful ‘tal-lal-lal-lal’) with propriety. This song contains an optional flute part doubling the melody printed at the bottom, a practice common at the time.

‘The Double Entendre’ (London, c. 1730) (Shelfmark: Rw.110.25/71)

good taste

When it comes to sharing food with others one should properly consider etiquette. John Tresidder Sheppard (1881–1968, KC 1900, Provost 1933–54) was elected to the debating society known as The Cambridge Apostles in 1902. In 1903 he presented a paper styled ‘May we eat cheese with a knife?’ in which he considered, among other things, the question of bad manners. He opined that vulgarity of manners is due to the shock that others experience when witnessing, for example, ‘the knife-tip in the mouth’ rather than that the person committing the offense, or the offense itself, is somehow inherently vulgar.

Paper read by JT Sheppard to the Apostles, 6 June 1903 (Ref: JTS/1/3/2). Page 1

Paper read by JT Sheppard to the Apostles (Ref: JTS/1/3/2). Pages 5-6

The Apostles gave their customary impenetrable vote on his question:

Apostles’ vote on Sheppard’s paper, 6 June 1903 (Ref: KCAS/39/1/14)

how they made it

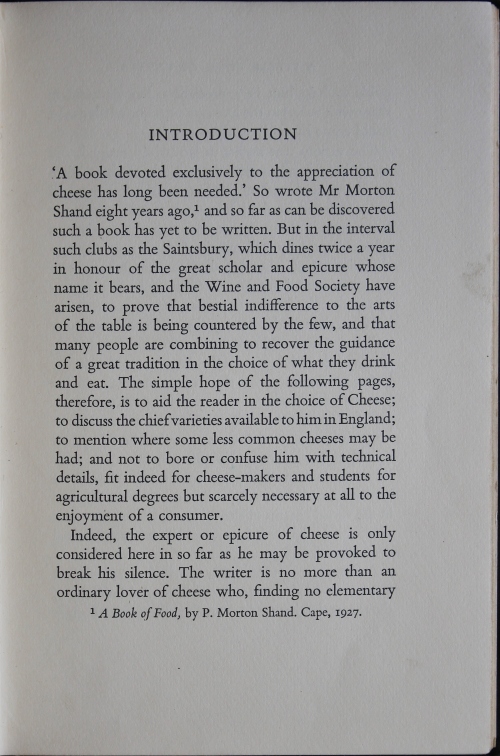

Another Kingsman, Osbert Burdett (1885–1936, KC 1903) also took the subject of cheese rather seriously. He wrote books about Blake and Gladstone (among others) as well as his rather humorous book A Little Book of Cheese which surveys English and foreign cheeses, shares some recipes and also incorporates tantalising titbits about the monstrous nature of smoking whilst enjoying cheese, all the while presenting us with curious facts such as which cheese was Thomas Hardy’s favourite!

Osbert Burdett, A Little Book of Cheese (London: Howe, 1935) (Shelfmark: UXL PSU Bur). Title page

Osbert Burdett, A Little Book of Cheese. Introduction

Osbert Burdett, A Little Book of Cheese. Page 87

Well, cheese is all very good, but what if you have a sweet tooth? In this charming little book, the Banbury cake—one of the more erudite cakes that we have—tells its own story! Banbury cakes have been made in Banbury in Oxfordshire since the sixteenth century. During the eighteenth century the recipe had become more similar to Eccles cakes, but had originally enjoyed a filling of currants, mixed peel, brown sugar, rum and nutmeg encased in an oval of pastry. Appropriate for afternoon tea, and often stocked in railway stations as well as being sent as far afield as Australia and America, Banbury cakes were also presented to Queen Victoria on her way to Balmoral each August.

The History of a Banbury Cake: an entertaining book for children (Banbury, 1830s) (Shelfmark: Rylands.C.Banb). Title page

The History of a Banbury Cake. Preface and Opening

Staying with children’s literature, here we have the first edition of Beatrix Potter’s story The Pie and the Patty-Pan, which tells the story of a cat called Ribby who invites a dog named Duchess for afternoon tea, for whom Ribby bakes a mouse pie. The book remained one of Potter’s favourites, and the illustrations are considered to be some of her most beautiful.

Beatrix Potter, The Pie and the Patty-Pan (London, 1905) (Shelfmark: Rylands.C.Pot.Pie.1905.a). Title page

Potter, The Pie and the Patty-Pan. Ribby baking the pie made of mouse.

Potter, The Pie and the Patty-Pan. Description of the pie made of mouse.

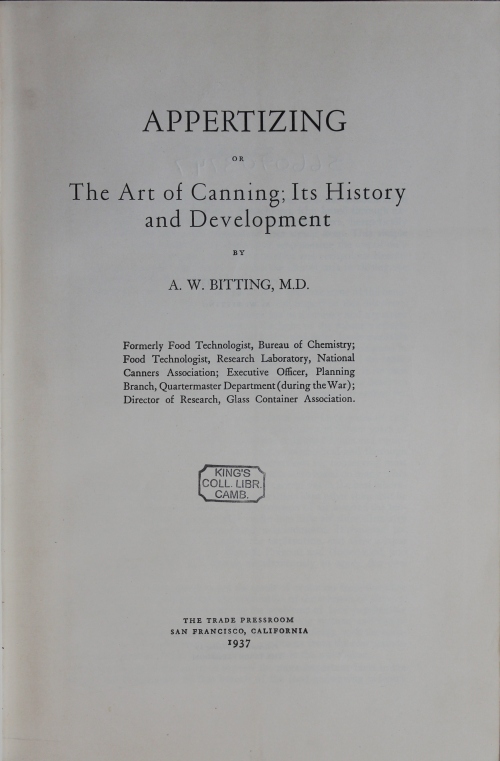

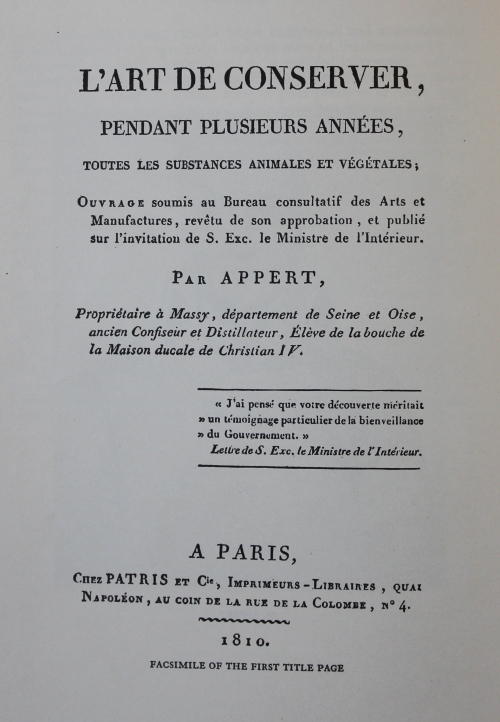

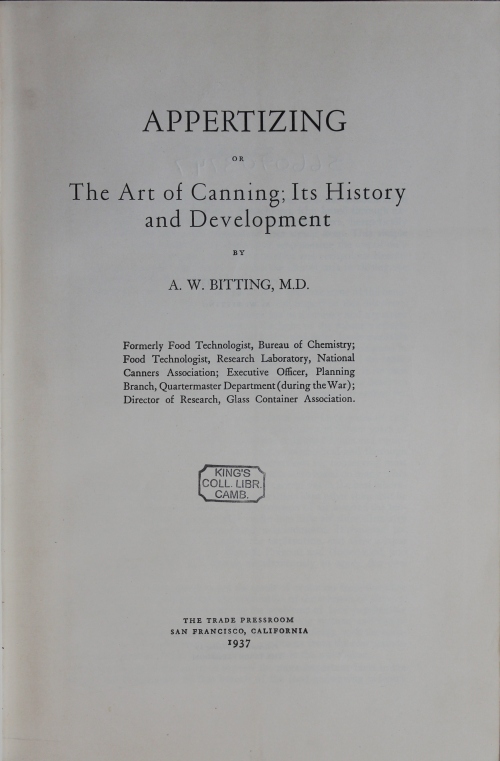

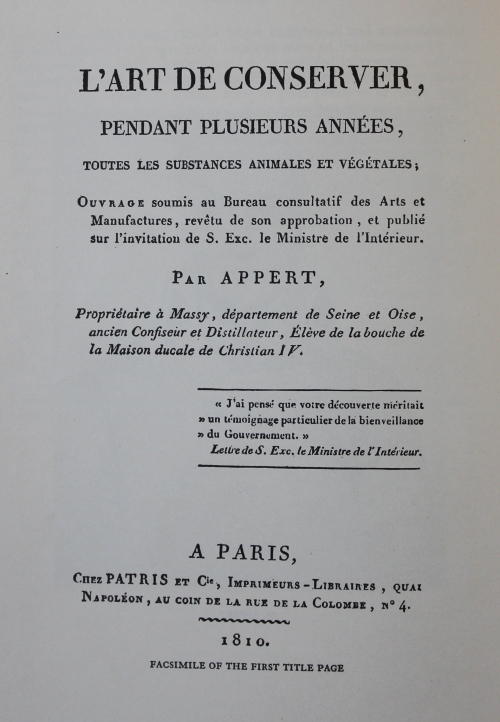

OK, that’s quite enough frivolity: time to get serious. Only the most ardent researcher of food history would attempt this enormous tome (852 pages) all about the techniques and history of canning food! That being said, it includes fascinating morsels about one of the most important men in the history of preserving food from whose research we have all benefited. Nicolas Appert (1749–1841), known as ‘the father of canning’, devised his new method for conserving foods by experimenting with placing them in air-tight glass jars that were then subject to heat. He published his results in 1810 in Paris as L’Art de conserver, pendant plusieurs années, toutes les substances animales et végétales. We’re sure many a feast has been had throughout the country after the shops have closed by raiding the back of the larder for tins of preserved food!

AW Bitting, Appertizing; or, The art of Canning; Its History and Development by A.W. Bitting (San Fransisco, 1937) (Shelfmark: CXM T Bit). Title page

Nicolas Appert (1749–1841)

Facsimile title page of Nicolas Appert’s treatise L’Art de Conserver (Paris, 1810)

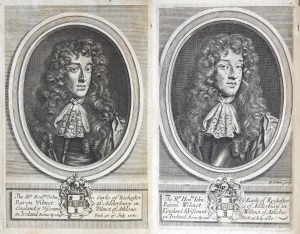

One cannot have a discussion about food without mentioning Apicius. Also known as De re culinaria or De re coquinaria (On the Subject of Cooking), Apicius is a collection of Roman recipes, thought to have been compiled in the first century AD. It has been attributed to various historical figures named Apicius, including the gourmet Marcus Gavius Apicius, although the connection is impossible to prove. The first printed edition appeared in Milan in 1498. Our edition, of which only 100 copies were printed, dates from 1709 and includes a commentary by Martin Lister (1639–1712), the English physician and naturalist, who related the material in the original work to medicine and healing.

Apicii Coelii De opsoniis et condimentis: sive arte coquinaria, libri decem. cum annotationibus Martini Lister (Amsterdam, 1709) (Shelfmark: M.37.52). Title page

Apicii Coelii De opsoniis et condimentis. Engraved frontispiece

Getting down to the nitty gritty of making food at King’s, bear in mind that the cooks were preparing food for around 100 fellows, scholars, choristers, lay clerks, chaplains and servants. Judging by the inventories, they seem to have had to do so in a kitchen less well-equipped than most modern British households. The kitchen inventory for 1598 (updated in 1605) notes 8 pots and pans with only 2 lids (for oven cooking), with the various necessary ironwork and tripods for suspending them over the fire (admittedly not part of most modern kitchens), a single set of bellows and tongs (the coal rake went missing sometime between 1598 and 1605), 4 skillets, 2 grills and an iron peele (for putting things into the oven and retrieving them again). There were only 2 ladles and 2 cooking spoons listed, 2 knives and a cleaver, a single colander and a grater. There was a mortar and pestle and also a querne for grinding the mustard. The food had to fit on 3 meat serving plates and 14 pie plates but there were dozens of other dishes and platters. Storage consisted of two large lead cisterns (presumably for water), a box (presumably wooden) for oatmeal and various probably wooden pails and tubs. What did they want with a wheelbarrow?

The King’s College kitchen inventory for 1598 and 1605 (Ref: KCAR/4/1/5/5, opening 19)

The brewhouse inventory in that same volume lists mash vats, wort vats, coolers, tuns, a fire fork and coal rake, pails, copper kettles and funnels, a pair of scales, 2 bushel baskets and a French fan, a hops basket and a horsemill. The bakery was equipped with, among other things, 2 stonking lead weights of 100 pounds each, and 2 smaller weights of 24 pounds each.

Where they got it

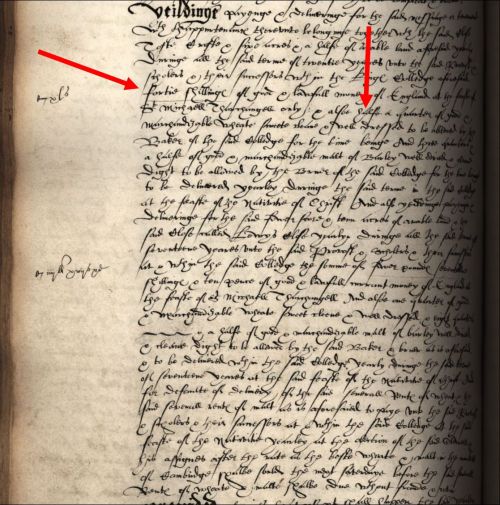

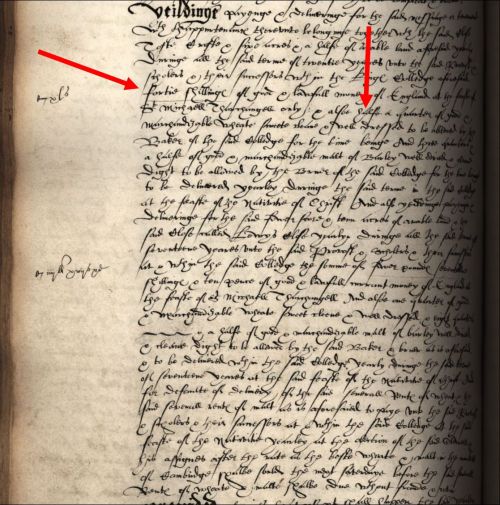

Who supplied our brewer and baker? An early College experiment with self-sufficiency in the form of a home farm in Grantchester had proven non-viable and certainly by 1570 the College got much of its wheat and malt as rent from our properties (endowed at the College’s foundation or acquired later), or bought it in the Cambridge markets and fairs. The cost depended upon whether it was delivered to College or not, and whether the barley was malted or not (we had a malt house) but it was definitely ground in the College’s mill house by the College’s mill horse. For example, one Grantchester tenant had to provide from his holding an annual rent of 40 shillings in addition to ‘halfe a quarter of good and marchandizable wheate sweete cleane and well dressed … and three quarters & a halfe of good & marchandizable malt of Barley well dried and cleene, eight to be allowed by the [College] bruer … to be delivered yearley’ to the College during Michaelmas term.

Part of a lease between King’s College and Otewell Hill for land in Grantchester, 2 October 1585 (Ref: KCAR/3/3/1/1/2, page 373)

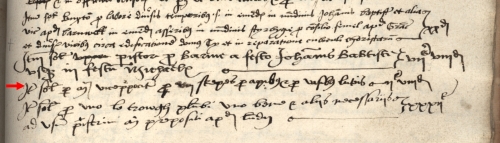

For meat and fruit, by the late sixteenth century the College had an orchard, a swan house and a pigeon house. Beef, like malt and wheat, was sometimes part of the rent due to us. For example the tenant at Prescot in Lancashire had to deliver ’12 fatt oxen, of a lardge bone, soe that the Bulke or Fower quarters of every of the said Twelve Oxen, killed [and with the organs removed], shall weigh ffortie Stone at the least … or else … Twentie pounds of good & Lawfull money of England, in lieu & full recompense’.

Part of a lease between King’s College and Charles Lord Strang (son and heir apparent to the Earl of Derby), 15 May 1649. (Ref: KCAR/3/3/1/1/5 fo 76v)

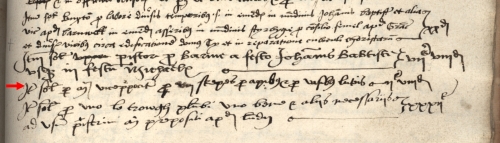

Large quantities of mutton and beef were also purchased: in the 1579–80 financial year for example, 1,757 stone of beef was bought (equivalent to over 10,000 kg) as well as about 750 sheep. 800 cod, 15 lings and two barrels of preserved herring were bought, and expenses for veal, milk, rabbits, pork, chickens and eggs all appear at feast times in the dining accounts, so apparently the College had no fish ponds, dairy herds, coney warrens, pigsties and/or hen houses. At least in 1533 we had bees, because we repaid the Vice-Provost 2 shillings 8 pence for bee skeps (skepes pro apibus) and clay vessels (vasilibus luteis).

Beekeeping expenses in the annual accounts for late summer 1533 (Ref: KCAR/4/1/1/10, exp. nec.)

Vegetables possibly came from a kitchen garden. Certainly there was a kitchen garden by 1899, and at some point pigs had been introduced: ‘The produce of our 2 kitchen gardens (about 7 acres) and orchard (about 1 acre – very poor) … includes early + late vinery, tomato + cucumber houses, greenhouses + forcing pits … all the plant houses have been rebuilt one by one since I took then over in 1893 and the orchard has been largely replanted. Pigs were formerly a great feature but I have abolished them … I recommend tomatos strongly – not cucumbers … Grape growing cannot be done cheaply on a small scale … The great use of the garden is to supply vegetables quite fresh and in variety. For instance except in full summer quite fresh salads are scarcely to be bought, and even then there is little but cos lettuce.’

Pages from a letter to the Bursar from the Head Gardener (25 May 1899) (Ref: KCD/26 pages 1, 4, 5, 6)

That’s the final course of our offerings at this sitting.

Bon appétit!

an invitation

The special collections are open to visitors by appointment. For further information email library@kings.cam.ac.uk or archivist@kings.cam.ac.uk.

Further Reading

Purchases of food are listed in the Commons Books (described here) and the Mundum Books (described here).

Copies of leases are found in the Ledger Books (described here).

For a discussion of the price of wheat around 1900, see Minchinton, W. E. “Agricultural Returns and the Government during the Napoleonic Wars.” The Agricultural History Review, vol. 1, no. 1, 1953, pp. 29–43.

This exhibition is part of the 2021 Open Cambridge Festival on the 2021 Heritage Open Day theme of ‘Edible England’. Details of all the other events can be found at https://www.opencambridge.cam.ac.uk/events

This exhibition is part of the 2021 Open Cambridge Festival on the 2021 Heritage Open Day theme of ‘Edible England’. Details of all the other events can be found at https://www.opencambridge.cam.ac.uk/events

GB/JC/PKM