In this second blog post marking 200 years of the modern railway, we focus mainly upon its arrival and early years in the Lake District, with a few other choice items from our collections making an appearance towards the end.

The arrival of the railway in the Lake District in the late 1840s markedly increased accessibility to a landscape that had been growing in popularity with tourists since the late eighteenth century. Here, just as in Cambridge, the guidebooks quickly adapted to reflect the new realities of travel.

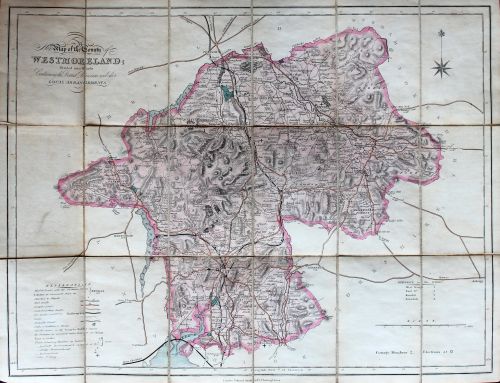

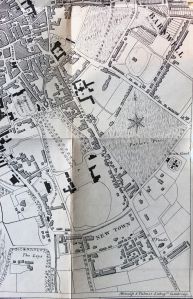

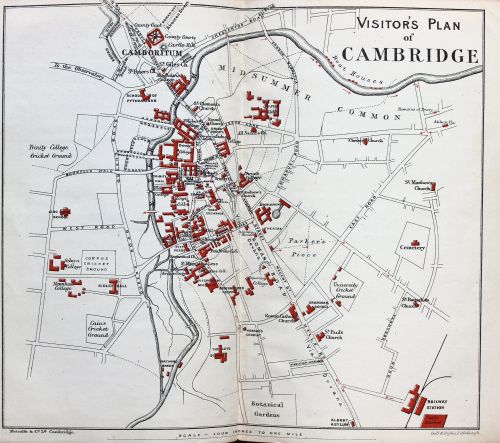

Likely one of the earliest railway maps of the region is the Collins’ Railway Map of Westmoreland, a small folded map mounted on linen, which would have made it durable and easily portable for use by travellers.

The map is undated, but examination of the railway lines that are indicated on it in black suggests a publication date of around 1847, since it depicts the railway line extending to Lake Windermere which opened in 1847, but not the line to Coniston which arrived in the following year.

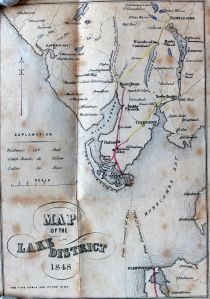

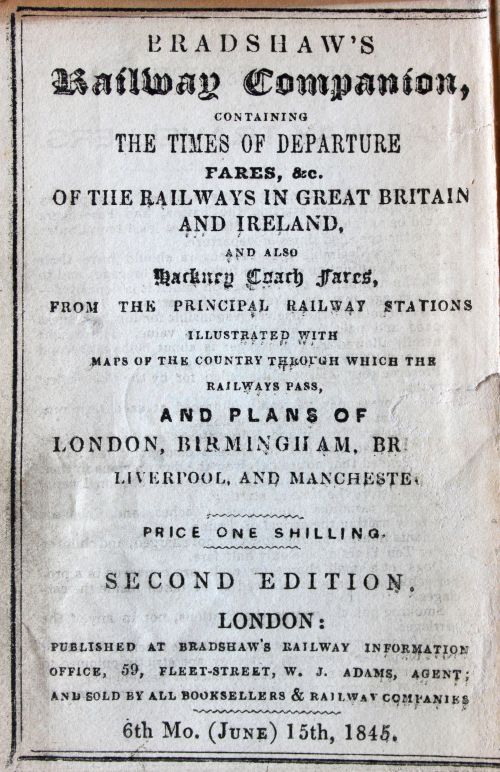

Another nice map can be found in a tiny pamphlet guide from 1848, which this time has rail lines marked in red.

Title page of The Lakes, By Way of Fleetwood and Liverpool …, Manchester, Bradshaw and Blacklock, 1848. Classmark: Bicknell 243

This guide includes timetables for steam ships and railways leading to the Lakes, alongside information about coaches to and from Keswick, which was not yet served by a rail line.

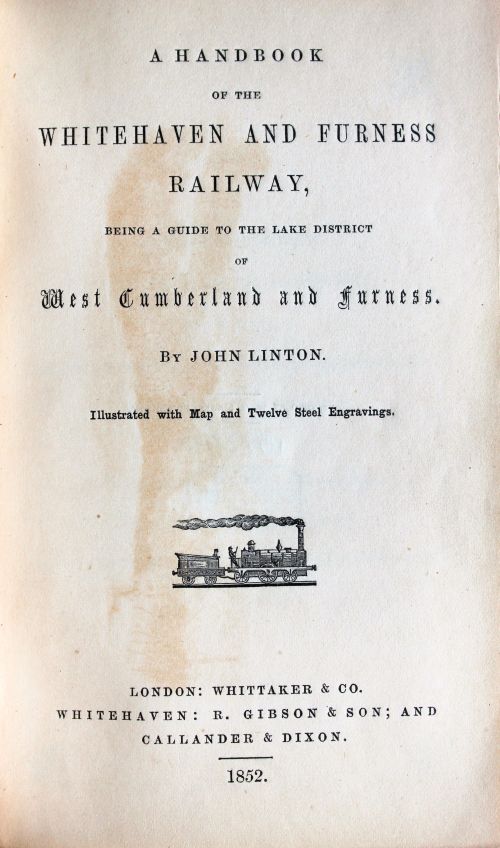

A slightly later guide focuses on areas made more accessible by the Whitehaven and Furness Railway, which opened in 1850. Note the sweet little title page vignette depicting a steam engine:

Title page of: A Handbook of the Whitehaven and Furness Railway by John Linton, London, 1852. Classmark: Bicknell.107

The guide states its purpose clearly (if a little long-windedly) in the introduction:

Our object is merely to supply what, in consequence of the changes recently effected by railway travelling in the approaches to this district, has become a desideratum; – to point out the routes by which the greatly increased number of tourists and others … may arrive at various interesting points of the district; – and to give brief descriptions of several places, all within an easy distance of the railway we have taken as our starting point, which have hitherto, owing to the difficulty of approaching them, been much less frequented …

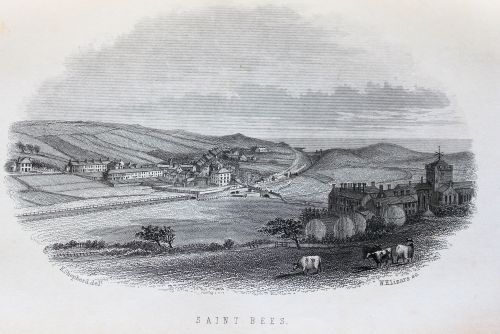

One such place is the vale of St. Bees, which is described as if viewed from a moving train. The guidebook goes into raptures about its charms:

After emerging from the cutting, we are again at liberty to enjoy the beauties spread so abundantly on either hand, and it may with truth be said, that a more pleasant and enlivening scene is very rarely met with than that presented to the traveller through the vale of St. Bees. It is a scene of quiet and repose, and yet of the highest cultivation, combining the varied charms of dale and upland, grove and meadow, stately mansion and thriving farm.

If you look closely at the centre of the accompanying engraving (below), you can see a train travelling along the track, trailing steam behind it.

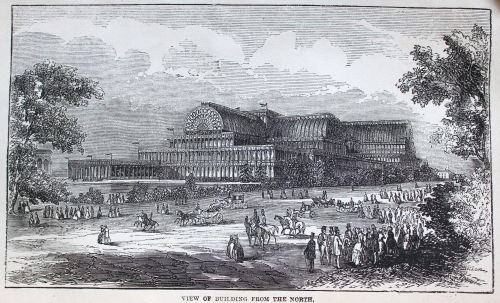

Rail access played an important part in the viability of many business ventures in the Victorian age. When the historic Great Exhibition in London’s Hyde Park, the world’s first international trade fair, closed its doors in October 1851, the future of the exhibition hall, the magnificent Crystal Palace, was initially uncertain. However, the designer Sir Joseph Paxton soon orchestrated the raising of enough private funds to purchase the building and have it re-erected in an adapted and enlarged form on a hilltop in Sydenham, in the south east of the city. An elaborate park was constructed around it and the site was opened to the general public in 1854 as a place for relatively cheap entertainment and recreation for the masses. Attractions included concerts, exhibitions, pantomimes, circuses and the delights of the building itself and the surrounding landscaped gardens. Vital to the success of the scheme was the construction, by the London, Brighton and South-Coast Railway Company, of a dedicated railway station for the site, which opened shortly after the park itself. Close co-operation with the railway was expedited by the fact that the chair of the railway company, Samuel Laing, was also chair of the new Crystal Palace Company. It also made commercial sense for the railway, since any big attraction would boost the growth of rail travel.

The illustration below comes from a little guidebook to the palace and park, published in its inaugural year. Our copy is part of the Thackeray Collection.

Frontispiece from Guide to the Crystal Palace and Park by Samuel Phillips, London, 1854. Classmark: Thackeray.VIII.11.24

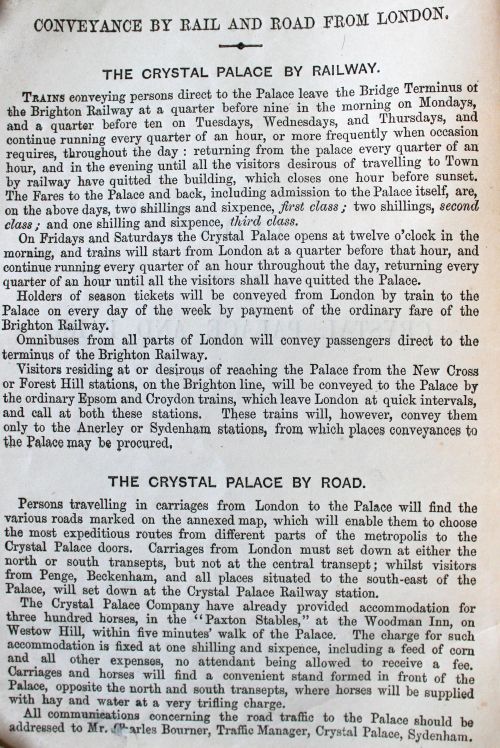

Detailed information on accessing the park by rail is provided inside the guide, revealing that the service ran at least every quarter of an hour and more frequently at busy times of day. Return tickets, which included admission to the Palace, were one shilling and sixpence for third class travel, rising to two shillings and sixpence for first class.

Incidentally, this guide includes an advertisement by the South Eastern Railway for what they refer to as: “tidal trains”, which offered a streamlined service between London and Paris. Passengers could board an express train to Folkestone, embark upon a waiting steamer ship and be met after the channel crossing by a direct train for Paris. Luggage would be managed from start to finish by the rail company. The same arrangements applied for a trip in the other direction. Not bad for the early decades of rail travel!

The final destination on our whistlestop tour of railway-themed material is our Rylands Collection of children’s books. An illustration from the first edition of Through the Looking Glass depicts Alice in a train carriage with some rather odd travelling companions.

Illustration by John Tenniel from page 50 of Through the Looking Glass, and What Alice Found There by Lewis Carroll, London, 1872. Classmark: Rylands.C.CAR.Thr.1872

We also hold a copy of Robert Louis Stevenson’s A Child’s Garden of Verses, which includes this wonderfully evocative poem about a train journey.

Page 68 of A Child’s Garden of Verses by Robert Louis Stevenson, London, 1896. Classmark: Ryland’s.C.STE.Chi.1896

We hope you’ve enjoyed this look at the early days of rail travel as reflected in our collections and that you enjoy any and all excursions you make this autumn and winter, whether by train or by any other means!

AC

References and further reading:

Railway 200 [accessed September 2025]

Lee Jackson, Palaces of pleasure: how the Victorians invented mass entertainment, New Haven, 2021

The Crystal Palace Foundation [accessed September 2025]