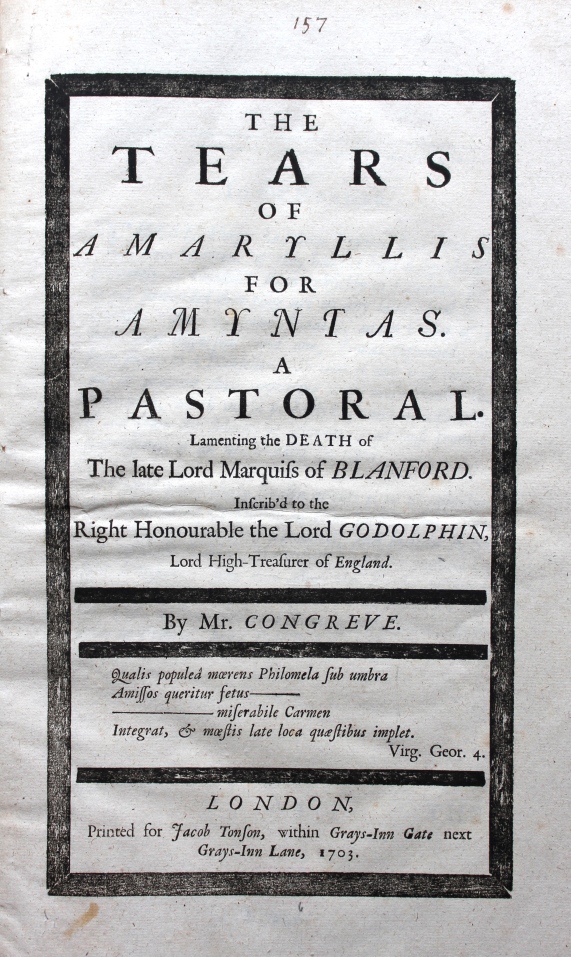

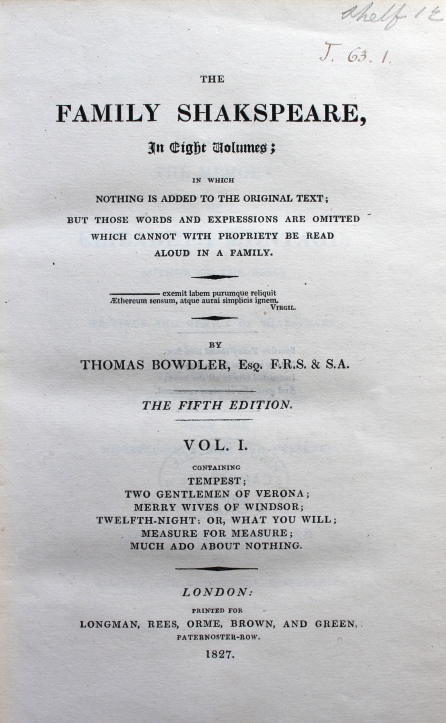

Last month, King’s College Library and Archives hosted an exhibition for the Open Cambridge weekend as part of the events marking the 400th anniversary of Shakespeare’s death. The exhibition, held on 9 and 10 September, showcased scarce editions of Shakespeare’s plays alongside other treasures from the special collections in the College Archive celebrating theatre and the history of theatre in Cambridge. Below are some selected highlights from the exhibition focusing on early editions of Shakespeare’s works.

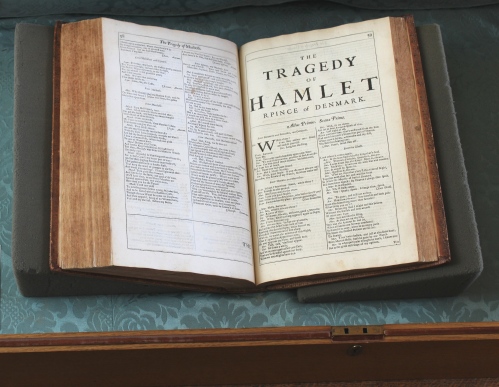

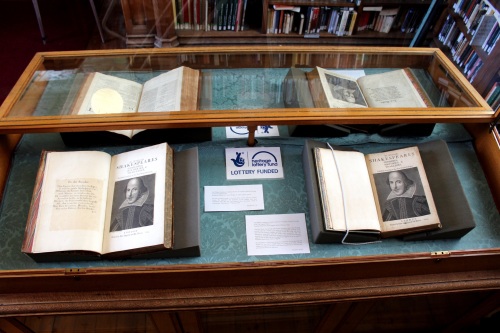

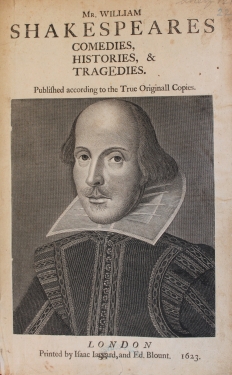

King’s College’s First Folio (1623) is one of only 234 known surviving copies. The title-page portrait in this copy is not original and appears to be an engraved facsimile. The importance of this book cannot be overstated. Pivotal plays like The Tempest, As You Like It, Twelfth Night, The Taming of the Shrew, Macbeth, Antony and Cleopatra, and Julius Caesar were printed here for the first time, and may have been lost otherwise. Next to it is the first facsimile reprint of the First Folio, edited by Francis Douce. The date has been derived from the paper, which is watermarked: Shakespeare. J. Whatman, 1807:

On the other side of the display case are the two other Folios from the Thackeray Bequest: the Second (1632) and the Fourth (1685). The printing of the former was carried out by Thomas Cotes and a syndicate of five other partners: Richard Hawkins, John Smethwick, William Aspley, Robert Allot, and Richard Meighen. This copy bears the “exceedingly rare” Hawkins imprint (Frank Karslake, Book Auction Records, London: William Dawson, 1903; p. 355):

![Mr. William Shakespeares Comedies, Histories, and Tragedies London: Printed by Tho[mas] Cotes, for Richard Hawkins, 1632](https://kcctreasures.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/10/second-folio.jpg?w=500&h=478)

Mr. William Shakespeares Comedies, Histories, and Tragedies

London: Printed by Tho[mas] Cotes, for Richard Hawkins, 1632

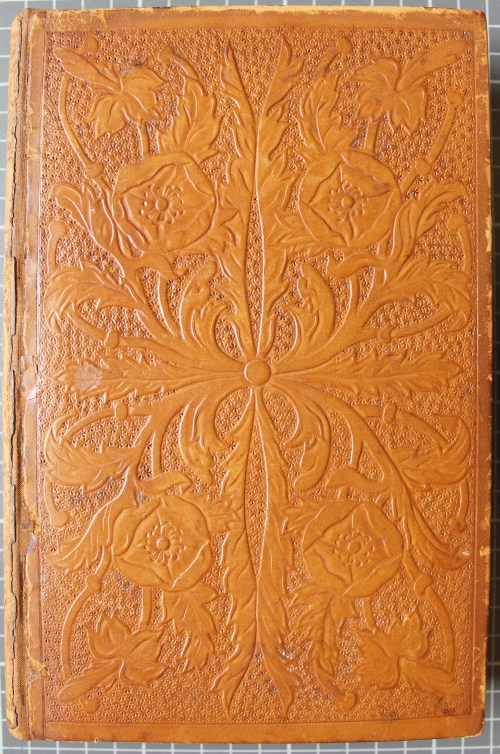

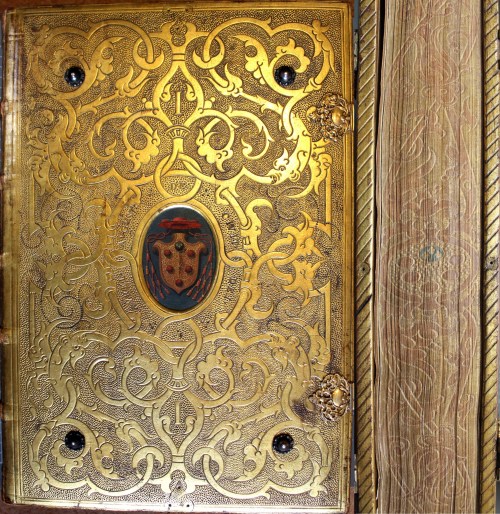

The Fourth Folio included seven additional plays: Pericles, Prince of Tyre; Locrine; The London Prodigal; The Puritan; Sir John Oldcastle; Thomas Lord Cromwell; and A Yorkshire Tragedy. All of these had been printed as quartos during Shakespeare’s lifetime, but only Pericles is now seriously considered to have any Shakespearean connection. The front board of this copy was completely detached; it was repaired in August 2016 thanks to the grant from the Heritage Lottery Fund.

Mr. William Shakespear’s Comedies, Histories, and Tragedies

London: Printed for H. Herringman, E. Brewster, and R. Bentley, 1685

As well as the Folio editions of Shakespeare’s plays, the exhibition also included early quartos of individual plays. This is a third edition of Henry V, a reprint of the second quarto of 1602. The imprint date is false, as the book was printed in 1619 for the Shakespearean collection of that year:

![William Shakespeare, The Chronicle History of Henry the Fift London: Printed [by William Jaggard] for T[homas] P[avier], 1608 [i.e. 1619]](https://kcctreasures.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/10/henry-v.jpg?w=500&h=407)

William Shakespeare, The Chronicle History of Henry the Fift

London: Printed [by William Jaggard] for T[homas] P[avier], 1608 [i.e. 1619]

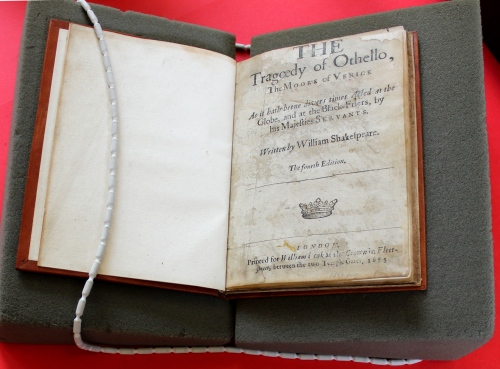

Below is a copy of the fourth edition of Othello. The play was entered into the Stationers’ Register on 6 October 1621 by Thomas Walkley, and the first quarto was printed by him in 1622.

William Shakespeare, The Tragoedy of Othello, the Moore of Venice

London: Printed for William Leak, 1655

Featured in the exhibition were also later editions of Shakespeare’s works. This 18th-century collection of his plays, edited by Kingsman George Steevens (1736-1800), includes a facsimile of Shakespeare’s will:

![The Plays of William Shakspeare: In Fifteen Volumes. With the Corrections and Illustrations of Various Commentators. To Which Are Added Notes by Samuel Johnson and George Steevens London: Printed [by H. Baldwin] for T. Longman, et al., 1793](https://kcctreasures.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/10/shakespeares-will.jpg?w=500&h=414)

The Plays of William Shakspeare: In Fifteen Volumes. With the Corrections and Illustrations of Various Commentators. To Which Are Added Notes by Samuel Johnson and George Steevens

London: Printed [by H. Baldwin] for T. Longman, et al., 1793

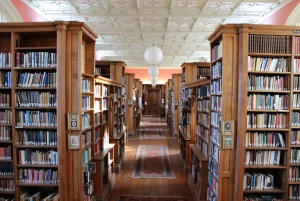

Despite inclement weather on the second day, the event was attended by more than 600 local people:

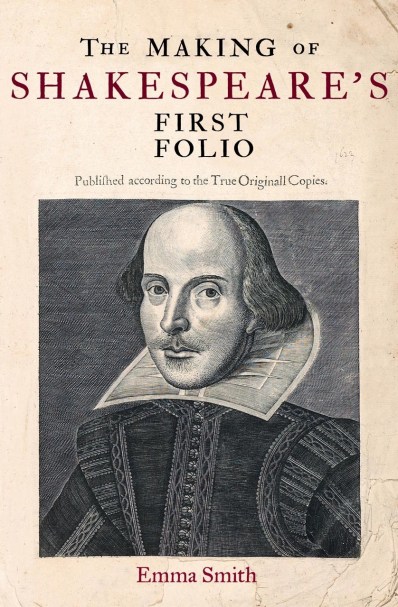

Our Shakespeare season culminated in a public lecture on the First Folio by a leading world expert, Professor Emma Smith (Hertford College, Oxford) on 3 October 2016. Professor Smith’s talk took the captive audience into the First Folio, and investigated the clues it gives us about Shakespeare’s writing methods, the early modern theatre, and the development of the Shakespeare brand.

IJ

![Peter Holland, Select Views of the Lakes in Cumberland, Westmoreland & Lancashire (Liverpool: printed by James Smith, for John Peeling, [1792]) Bicknell.61](https://kcctreasures.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/05/bicknell-61.jpg?w=516&h=405)

![Stebbing Shaw, A tour, in 1787, from London, to the Western Highlands of Scotland (London: printed for L. Davis, Messrs. Robson and Clarke, W. Lowndes, H. Gardner, J. Walker, [1788]) Bicknell.27](https://kcctreasures.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/05/bicknell-27.jpg?w=500&h=399)

![Thomas Rose, Westmorland, Cumberland, Durham, & Northumberland (London: Fisher & Jackson, [1832-1835]) Bicknell.85](https://kcctreasures.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/05/bicknell-85.jpg?w=500&h=388)

![John Smith, Sixteen Views of the Lakes in Cumberland and Westmorland (London: printed for W. Clarke [1794-1795]) Bicknell.84](https://kcctreasures.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/05/bicknell-84.jpg?w=500&h=370)