Given the importance of horses in human history we were inevitably spoilt for choice when it came to selecting equine-related images to celebrate the Lunar New Year of the Horse. What follows, therefore, is a first instalment which focuses on working horses in spheres such as agriculture, transport and warfare. A future post will cast a spotlight upon horses as they have been depicted in myth, legend and fables.

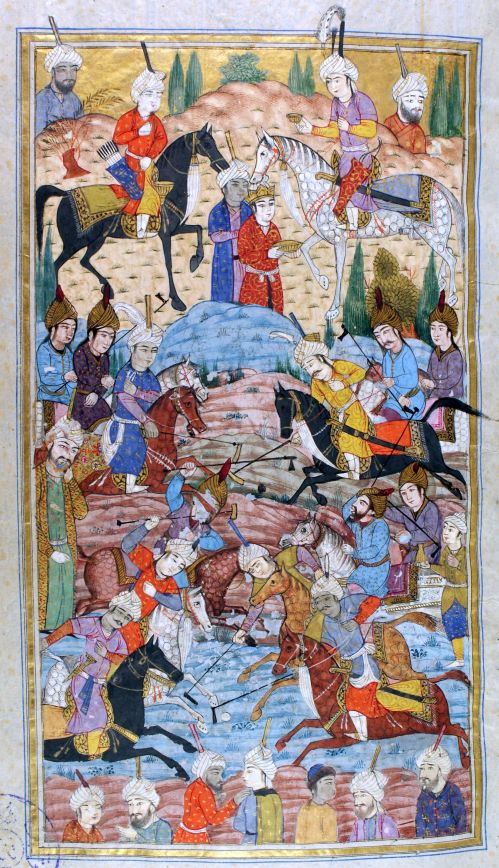

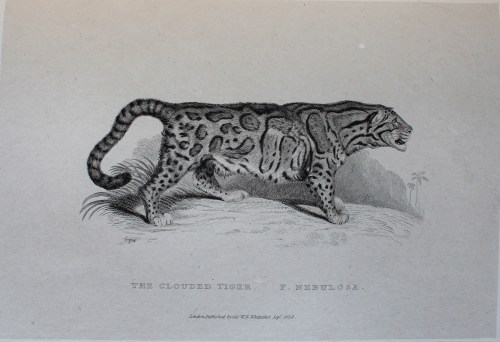

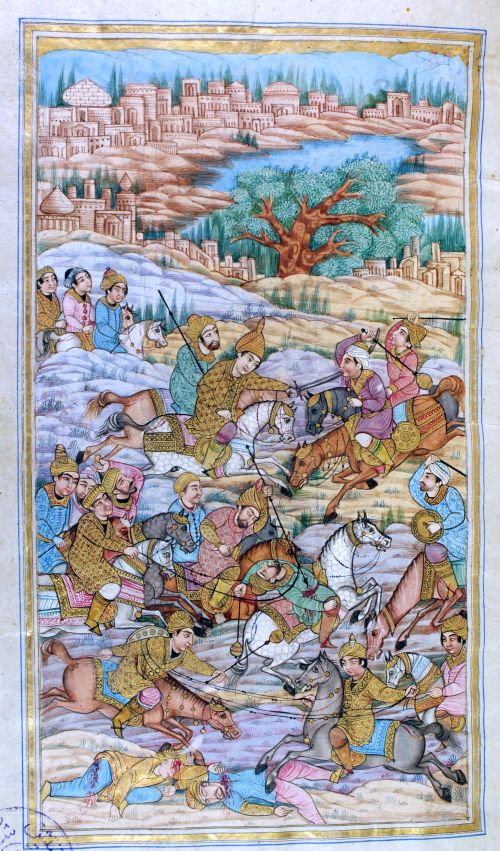

To kick things off with a bang, we begin with a highly dramatic battle scene involving a close-quarters skirmish between two opposing cavalry forces. This vibrant illustration comes from an early nineteenth-century Persian manuscript edition of the complete works of the Persian poet Saʻdī (ca. 1200-ca. 1292). It was given to the Library by Kingsman Martin Bernal (1937-2013), who acquired it from his grandfather, the Egyptologist Sir Alan Gardiner (1879-1963). Gardiner likely purchased it in Cairo in the first decade of the twentieth century.

Battle scene from a manuscript edition of The Complete Works of Saʻdī, probably produced in Shiraz, Iran, in 1837. Classmark: MS.26.c.16

The manuscript also contains a lively illustration of a polo match, featuring more elegant and diversely coloured horses. The sport has Persian origins dating back to around the 6th century BCE.

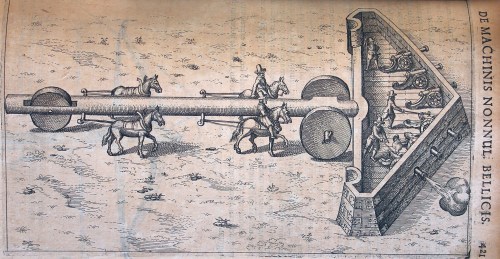

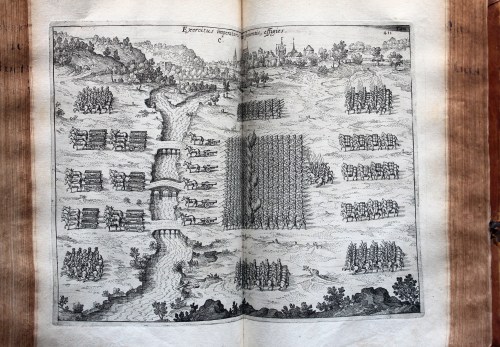

Returning from that sporting diversion to the more serious topic of warfare, we turn next to a much more regimented military scene, which comes from the second volume of Utriusque cosmi … historia, a primarily cosmological work by physician and occult scholar Robert Fludd (1574-1637). Horses are depicted here not only as cavalry animals, but also as a means of transporting cannons and baggage.

Plate from volume 2 of Utriusque cosmi maioris scilicet et minoris metaphysica, physica atque technica historia by Robert Fludd, Oppenheim, 1617. Classmark: F.27.04

Fludd travelled abroad in the years after finishing his education and may have acquired some military experience then. If not, he at least developed a deep interest in the subject. Amongst numerous designs for military fortifications and machinery in this work is a horse-driven mobile battery intended for breaking through enemy ranks. It is not clear whether such a machine was ever used on a battlefield, or how practical it would actually be.

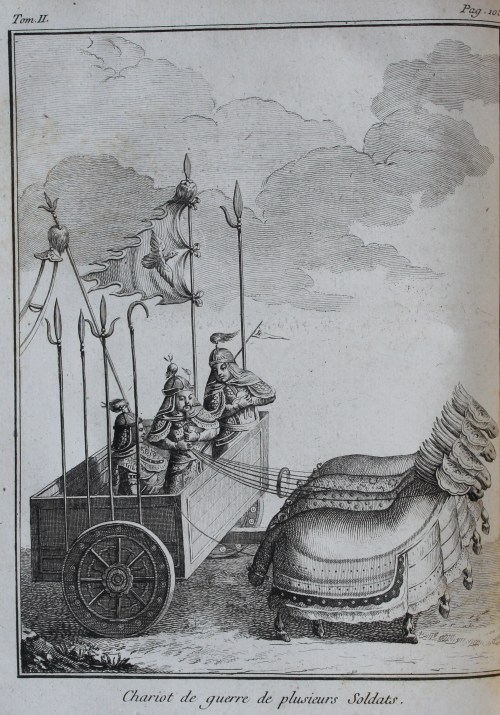

Heavily armoured horses pulling war chariots feature in an early eighteenth-century French translation of a twelfth-century work of Chinese history, the Zizhi Tongjian Gangmu. The translator was Joseph-Anne-Marie de Moyriac de Mailla (1669-1748), a Jesuit missionary to China who developed a great interest in Chinese history and learnt the Manchu language in later life. Accompanying illustrations in his text show both a large horse-drawn chariot carrying three soldiers and the slightly smaller but more embellished chariot of a General. The horses, resplendent in their elaborate head-pieces, look alert and well disciplined.

Plate facing page 105 in volume 2 of Histoire générale de la Chine translated by Joseph-Anne-Marie de Moyriac de Mailla, Paris, 1777. Classmark M.44.30

The library holds a copy of The History and Art of Horsemanship by Richard Berenger (1719 or 20-1782), who was Gentleman of the Horse to King George III. It contains this amusing illustration of a Sarmatian rider and his horse, both completely covered in scale armour. The Sarmatian people were skilled equestrians who roamed the steppes of central Asia from the 5th century BCE to the 4th century CE. Whilst they did indeed use scale armour, it is hard to imagine that it can have been quite as form-fitting as this image suggests!

Sarmatian horse and rider from plate 2 of volume 1 of The History and Art of Horsemanship by Richard Berenger, London, 1771. Classmark: Bryant.M.10.17

Martial images of horses can also be found in the stained glass of the College Chapel. They include this roundel depicting Joshua, who, according to the Bible, was successor to Moses as leader of the Israelites and led the conquest of the land of Canaan. The horse is at full gallop and Joshua has his lance held ready for action. He might be hampered though by the fact that his helmet appears to be covering his eyes!

At the very top of window 12.2 in the main part of the Chapel, two mounted warriors face off. The warrior on the left is rendered in the act of throwing his spear, whilst the horse of the one on the right is rearing back with what appears to be a spear or an arrow sticking out of its torso.

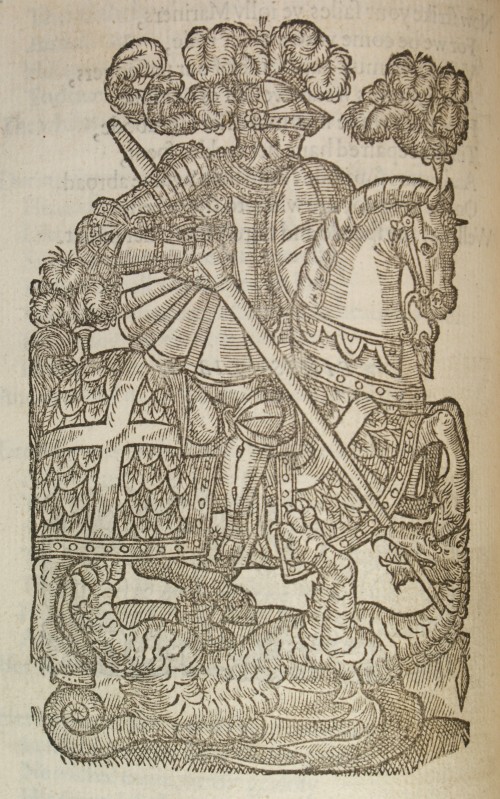

Some lovely illustrations of jousting knights and prancing horses can be found in a seventeenth-century French book all about medieval tournaments, pageants and spectacles by Claude-François Menestrier (1631-1705). Menestrier was a Jesuit, a courtier and an expert on heraldry. He also had extensive experience of his own in organising celebrations, parades and festivities in his home city of Lyon. This included organising the festivities surrounding the visit of Louis XIV to the city in 1658.

Jousting knights from page 103 of Traité des tournois, ioustes, carrousels, et autres spectacles publics by Claude-François Menestrier, Lyon, 1669. Classmark: Thackeray.H.28.13

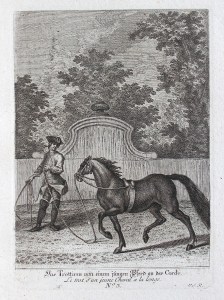

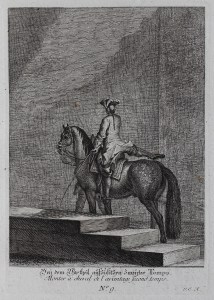

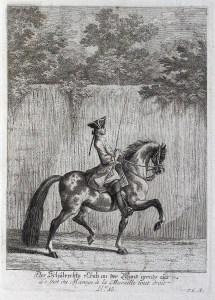

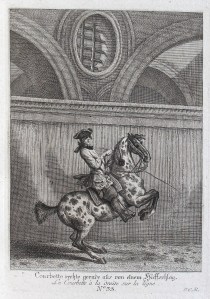

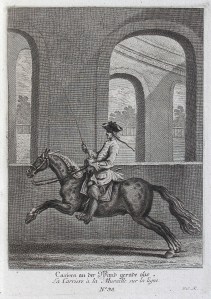

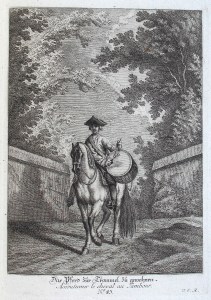

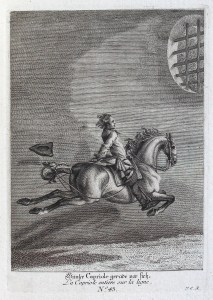

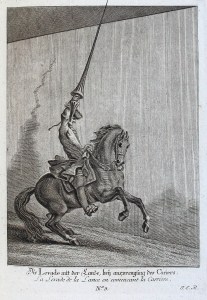

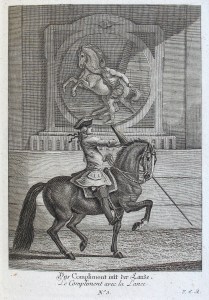

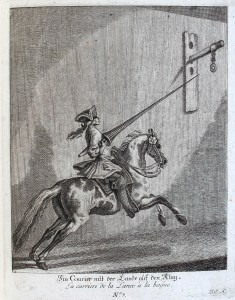

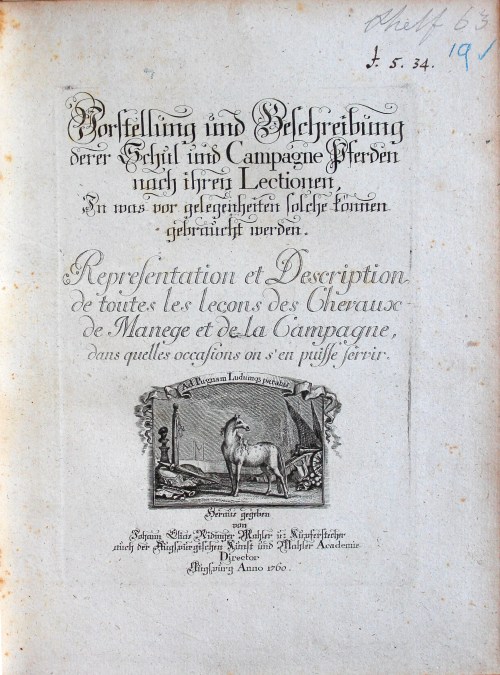

It would be remiss of us not to include a substantial helping of engravings from a wonderful volume by Johann Elias Ridinger (1698-1767), a noted German artist, who specialised in painting and sketching animals, especially horses. Ridinger spent three years observing and sketching at a riding school and this experience shines through in the quality and realism of his work. The engravings below illustrate many aspects of equestrian training, including learning the use of weapons and military drums on horseback.

Title page of Vorstellung und Beschreibung derer Schul und Campagne Pferden nach ihren Lectionen, in was vor Gelegenheiten solche können gebraucht werden by Johann Elias Ridinger, Augsburg, 1760. Classmark: Thackeray.F.5.34/1

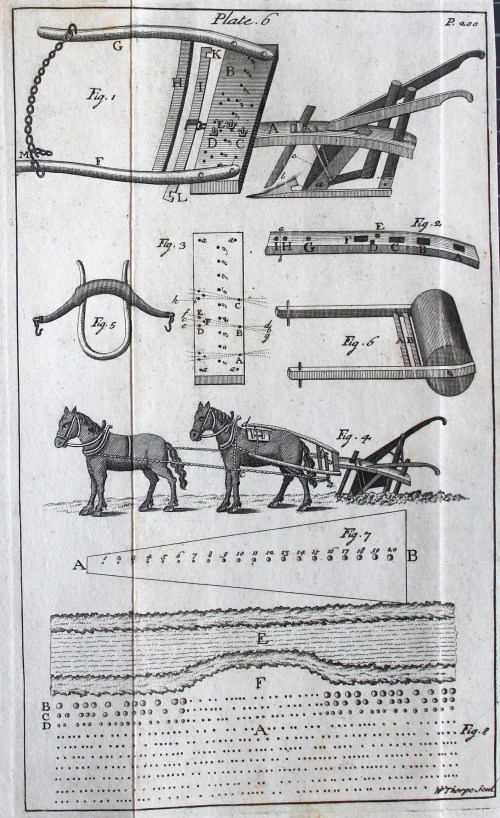

We transition now to the more peaceable occupation of agriculture, in which horses have also played an important role for centuries. The Keynes Collection includes a copy of The Horse-Hoing Husbandry: or, An Essay on the Principles of Tillage and Vegetation by agriculturist Jethro Tull (1674-1741). Tull’s innovative designs for agricultural machinery, including a horse-drawn seed drill and a horse-drawn hoe for tilling the soil, helped foster a major revolution in agricultural practices and productivity in eighteenth-century Britain. His book provides detailed instructions for building and using these machines, accompanied by useful diagrams, such as the one of the “Ho-Plow” which is included below.

Title page of The Horse-Hoing Husbandry: or, An Essay on the Principles of Tillage and Vegetation, by Jethro Tull, London, 1733. Classmark: Keynes.F.23.4

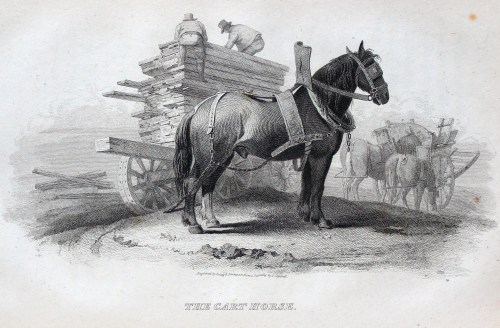

By the time Tull was writing it was common practice to use large, muscular draught or cart horses to pull farm machinery and other heavy loads. Prior to this period, agricultural yields of winter crops had not been high enough to provide the large amount of food such horses required to function. The poor horse pictured below is awaiting the task of pulling a wagon piled precariously high with wooden planks!

Plate facing page 165 of Recreations in Natural History; or, Popular Sketches of British Quadrupeds engraved by Luke Clennell, London, 1815. Classmark: Thackeray.IV.2.1

The use of horses for agricultural tasks is not entirely a thing of the past, and indeed, the glorious wildflower meadow on our College back lawn is harvested each August by a team of shire horses from the Waldburg Shires Stables in Huntingdon. The horses are later attached to a hay wain to remove the baled-up hay. This use of traditional methods helps to minimise the carbon footprint of the whole process. The photos below were taken during the very first harvest in the summer of 2021.

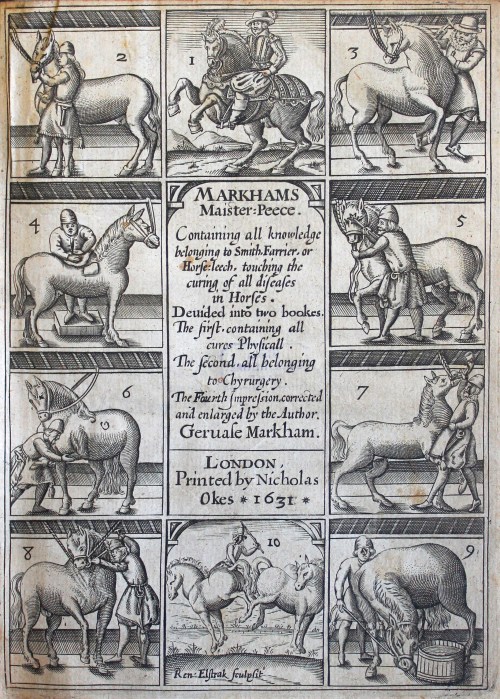

Of course, in order for horses to be fit and strong enough to undertake all the many tasks that humans have found and still find for them, they ideally need a great deal of care and attention. Our final image is from a seventeenth-century veterinary text, Markhams Maister-Peece…, which is devoted to curing all the various ailments suffered by horses. The author, Gervase Markham (1568?-1637), was a poet and literary figure who also wrote on a wide variety of practical subjects, including equestrian matters. For this he drew upon his considerable experience as a horse breeder and farmer. The engraved frontispiece below illustrates various aspects of caring for horses, including diet, treating wounds and sores and tending to strained legs. The figure at the top-centre is intended to embody the ideal outcome of all this care: “The figure 1, a compleat horse-man showes, that rides, keepes and cures, and all perfections knows.”

Engraved frontispiece from Markhams Maister-peece: Contayning All Knowledge Belonging to the Smith, Farrier, or Horse Leech, Touching the Curing of All Diseases in Horses by Gervase Markham, London, 1631. Classmark: Chawner.A.6.29

We hope you have enjoyed this canter around our collections!

AC

References and further reading:

Juliet Clutton-Brock, Horse power: a History of the Horse and the Donkey in Human Societies, London, 1992

Hilary Wayment, The Windows of King’s College Chapel Cambridge, London, 1972

Hilary Wayment, King’s College Chapel Cambridge: the Side-Chapel Glass, Cambridge, 1988

Matthew Steggle, Markham, Gervase (1568?-1637) Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. 28 Sep. 2006 [Accessed February 2026]

BBC news story: Cambridge University’s King’s College meadow harvested with horses, 2 August 2021 [accessed February 2026]