The many libraries of the University of Cambridge host an incredibly diverse range of books, manuscripts, and historic documents, some of which are over a thousand years old. That such documents are still available to us in a readable state is a tribute to the care and dedication of generations of librarians curating these collections.

We must remember that books are made of relatively vulnerable materials: papers and parchments. They are easily torn, creased, or stained through careless handling, but also damage caused by the environment such as mould, insects, water, or their arch-enemy: fire. When such damage occurs or is found on objects, librarians can call on the services of the book conservators at the Cambridge Colleges’ Conservation Consortium.

Here is the example of a 1507 book from the King’s College Library collection, “The Boke named the royall” printed by Wynkyn de Worde, an extremely important printer based in London, known for his work with William Caxton who was the first to popularise the use of the printing press in England.

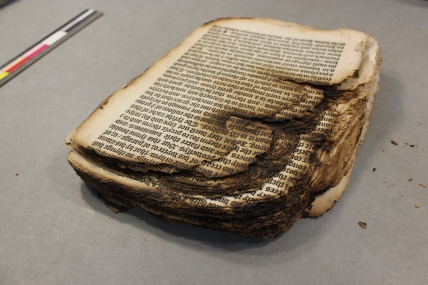

The volume is printed on handmade paper with many beautiful wood-block print images, but it has obviously suffered extensive damage caused by fire. The previous binding structure and the covers had been completely destroyed, leaving only loose sheets with fire-damaged edges. When or how this fire happened is not documented, but we know that the book has been stored in this way since at least the 1980s.

A typical issue with fire-damaged books is that the pages, especially the edges, become very brittle and cannot be manipulated without causing further damage, meaning that the librarians at King’s could never allow this book to be consulted by researchers. Was there any way to make these 162 fragile leaves accessible again to scholars and researchers? This is the question that was put to me by the King’s College Librarian in 2022. This was a challenge, requiring very precise work, but the answer was a definite yes.

The first stage of the work was to re-order the leaves properly using a combination of clues, including the handwritten folio numbers and the signature letters and numbers printed on the leaves. This allowed us to identify that a number of the initial leaves were missing, possibly destroyed in the fire that caused the damage.

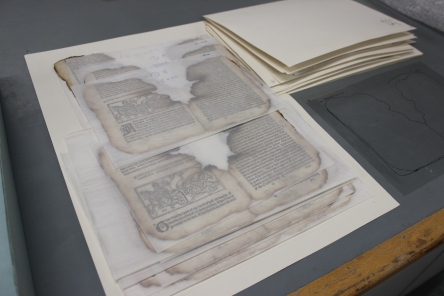

Each leaf was then washed following a four-stage process: a gentle surface dirt cleaning using a soft brush and a smoke sponge (a sponge made of natural vulcanized rubber). A water bath to dissolve impurities and stains in the paper. An alkali bath to stop acidic degradation of the papers, especially strong after fire damage. Lastly, a gelatine bath to “size” the papers to make it less brittle. It was truly delightful when I discovered several types of pretty watermarks during these washing processes.

Then came time to infill the losses and to reinforce the damage along the edges by using layers of two different weights of Japanese papers. Japanese papers are very fine, strong and flexible, almost transparent and alkaline or neutral making them perfect for conservation work. This process is essential to restore mechanical robustness of the leaves and allow handling. It is important to note that beyond these mechanical objectives, aesthetics must be considered, with each infill paper being pre-toned to colour match the original material.

After all leaves had been treated, dried, and pressed, the excess repair papers were trimmed.

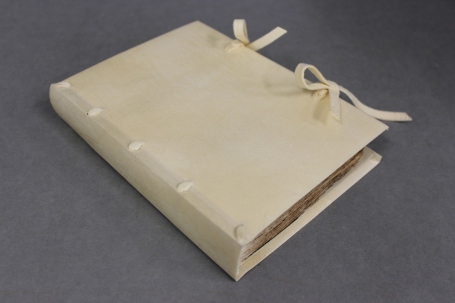

The volume was rebound in a historically compatible yet conservation quality “limp vellum” binding.

Finally, a bespoke box was built to house the newly rebound volume.

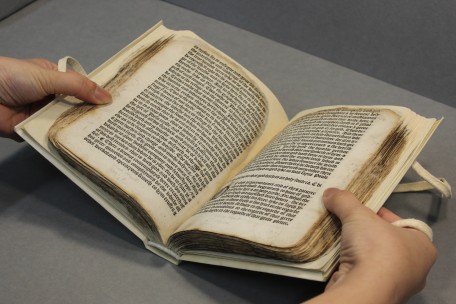

This was a very challenging but satisfying project and I am very pleased to have contributed to the preservation of this volume which can now be consulted, although, of course, still with careful handling.

One last gift: after the treatment, I looked at the aligned fore-edges, and I found the edge is partially glistened in gold! That means that the book had gold-tooled edges when the fire occurred.

As always, these projects are never solo work, and I must extend my deepest thanks to:

- My colleagues Lizzie Willetts and Hollie Drinkwater who helped during the washing and repair stages.

- My manager Flavio Marzo for his advice and constant support, especially on limp vellum binding.

- Dr James Clements, College Librarian at King’s College Library for entrusting me with such a wonderful project.

Mito Matsumaru, Book and Manuscript Conservator at Cambridge Colleges’ Conservation Consortium