Today, 16 December 2025, marks the 250th anniversary of Jane Austen’s birth. Events have been held throughout the year to celebrate this occasion. As part of Open Cambridge on 17 September, King’s College Library mounted an exhibition featuring first editions of all of Austen’s novels, the autograph manuscript of her unfinished novel Sanditon, a manuscript letter to her publisher, a book from her library, early translations of her novels, and other rare items. The event was a great success and was attended by over 650 people who braved the wet weather to come and view the treasures on display, thus creating a “ceaseless clink of pattens” on the wooden library floor reminiscent of Lady Russell’s description of driving through Bath on a wet afternoon in Persuasion. We present below some highlights from the exhibition for those who could not visit in person.

Sense and Sensibility, Austen’s first novel to be published, was written in epistolary form around 1795 in Steventon under the title Elinor and Marianne. It was begun in its present form in autumn 1797 and revised and prepared for publication in 1809-1811 when Jane was living in Chawton.

Pride and Prejudice, originally titled First Impressions, was offered for publication to the London bookseller Thomas Cadell, but the offer was declined by return post. The novel was subsequently published by Thomas Egerton under the revised title Pride and Prejudice. Upon receiving her copy of the first edition from the publisher, Jane wrote: ‘I have got my darling child from London’ (27 Jan 1813).

The Austen family lived in Bath between 1801 and 1806. Jane was familiar with the Pump Room, a venue for fashionable people, which is used as a setting in her novels Northanger Abbey and Persuasion. This image, from The New Bath Guide (1807), shows the Pump Room as it would have looked during Jane Austen’s time there.

Christopher Anstey, The New Bath Guide; or, Memoirs

of the B.N.R.D. Family in a Series of Poetical Epistles (Bath, 1807)

Warren.B.97.New.1807

Austen’s novels Persuasion (written 1815-16) and Northanger Abbey (written 1798-99) both appeared posthumously in a four-volume set in December 1817, although the title page states 1818. They are prefaced by a ‘biographical notice’ written by Jane’s brother Henry Austen in which Jane’s identity is revealed for the first time. She appears to have intended to publish Persuasion in 1818 but did not live long enough to do so.

Jane Austen, Northanger Abbey, and Persuasion (London: Murray, 1818), First edition

Thackeray.J.57.12-15

In 1809 Austen’s brother Edward offered his mother and sisters a more settled life – the use of a large cottage in Chawton, near Alton in Hampshire. Whilst living in Chawton Jane published her first four novels. She also wrote Mansfield Park there between 1811 and 1813. It was first published by Egerton in 1814 and a second edition was published in 1816 by John Murray, still within Austen’s lifetime. It did not receive any critical attention when it first appeared.

When Henry Austen was taken ill in London in October 1815, he was attended by his sister Jane and by one of the Prince Regent’s doctors who identified her as the author of Pride and Prejudice. The doctor reported that the Prince (later George IV) was a great admirer of her novels and she was invited to dedicate one of her future works to the Prince. Emma was the lucky work. Jane disapproved of the Prince’s treatment of his wife, but felt she couldn’t refuse, so she settled for a title page reading simply ‘Emma, Dedicated by Permission to HRH The Prince Regent’, though her publisher (John Murray) thought it ought to be more elaborate.

This copy of the first edition of Emma belonged to King’s Provost George Thackeray (1777–1850).

Several months after the dedication of Emma, Jane wrote to John Murray and reported that the Prince had thanked her for the copy of Emma. In the same letter she notes that in a recent review of the novel, printed in The Quarterly Review (vol. XIV, 1816), the anonymous reviewer (later established as Sir Walter Scott) completely fails to mention Mansfield Park, remarking with regret that ‘so clever a man as the reviewer of Emma, should consider it as unworthy of being noticed’.

Among the miscellaneous items on display was one of the few known copies of Sense and Sensibility in yellowback. Chapman and Hall’s series ‘Select Library of Fiction’ was closely associated with W.H. Smith, who carefully sought out copyrights, or reprint rights, of popular novels in order to publish yellowback editions for sale on his railway bookstalls. The series, which ran from 1854 until it was taken over by Ward, Lock in 1881, included at least thirty novels by Anthony Trollope, who had strong views on the poor quality of much railway literature.

One of the highlights of the exhibition was Jane Austen’s copy of Orlando furioso, signed by her on the fly-leaf, sold by the Austen-Leigh family, bought by Virginia Woolf, and inscribed by Woolf to John Maynard Keynes at Christmas 1936.

Ludovico Ariosto, Orlando furioso (trans. by John Hoole)

(London: Charles Bathurst, 1783)

Keynes.E.4.1

These Victorian editions of Mansfield Park, Emma, and Northanger Abbey were presented to E. M. Forster’s mother by his father, and were later inherited by Forster himself.

Copies of Mansfield Park, Emma and Northanger Abbey from the library of E. M. Forster (all London: Routledge, 18–)

Forster.AUS.Man; Forster.AUS.EMM; Forster.AUS.Nor

King’s College owns the manuscript of Jane Austen’s unfinished novel Sanditon, the last one on which she was working before she died on 18 July 1817. It is a rare surviving autograph manuscript of her fiction. It was given to King’s in 1930 by Jane’s great-great niece (Mary) Isabella Lefroy in memory of her sister Florence and Florence’s husband, the late Provost Augustus Austen Leigh who was a great-nephew of Jane. The booklets were made by Austen herself. The last writing is dated 18 March 1817. She died four months later.

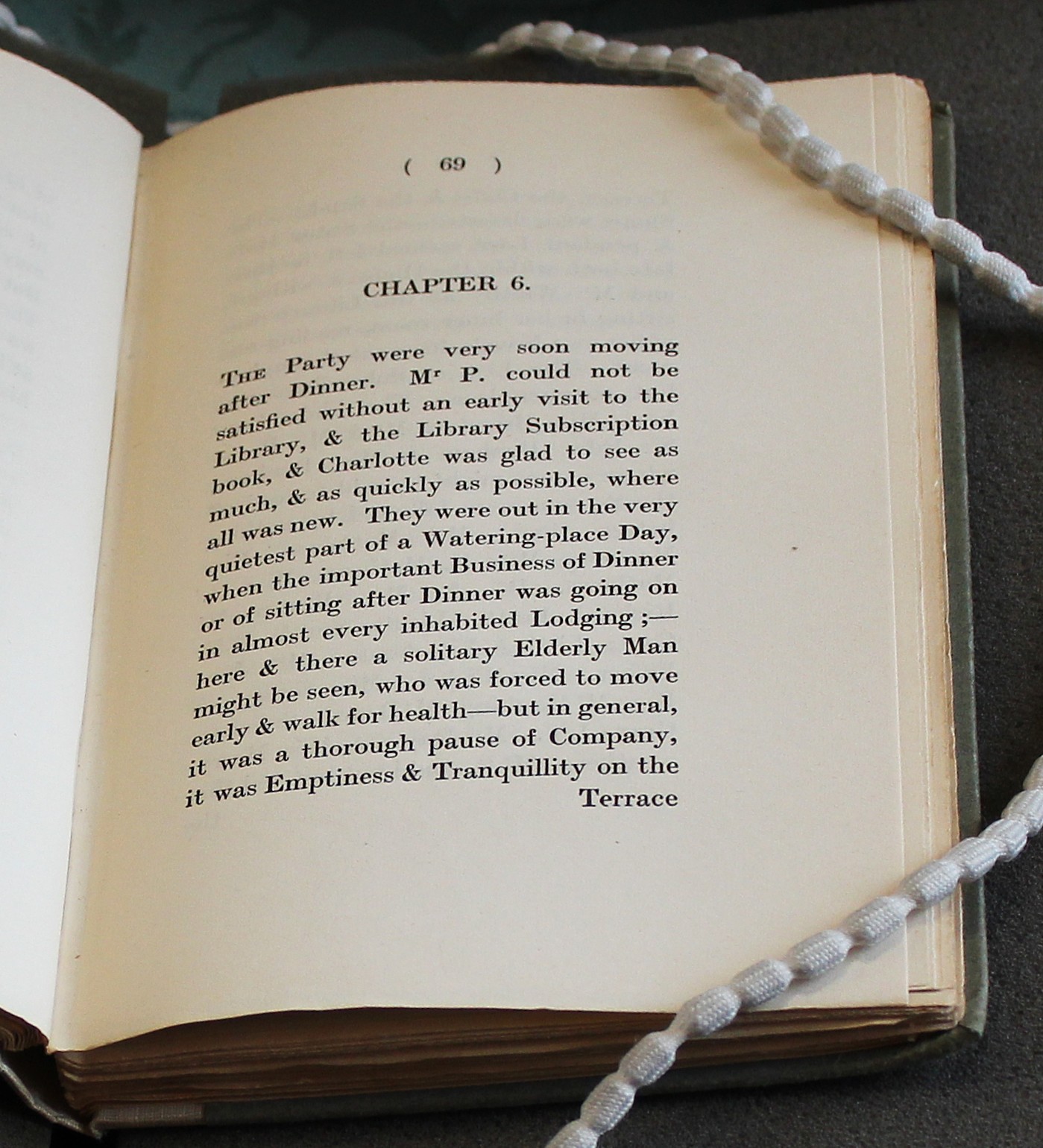

Below is the beginning of chapter 6, followed by the transcription in the printed version of Sanditon.

This copy of the first edition of Sanditon comes from the library of E. M. Forster.

Jane Austen, Fragment of a Novel (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1925)

Gilson.A.Sa.1925a

During the summer, King’s College loaned one of the fascicles of Sanditon to Harewood House to be displayed there as part of their exhibition ‘Austen and Turner: A Country House Encounter’ where it occupied pride of place and was viewed and admired by thousands of visitors.

JC/IJ