We recently mounted a small exhibition on the subject of moon exploration, using items from our collections. In case you didn’t get to see it, here’s an online version of some of the exhibits.

***

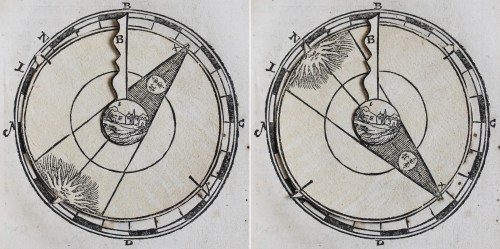

Johannes de Sacrobosco (born c.1195) was one of the most influential pre-Copernican astronomers, his treatise De sphaera mundi surviving in hundreds of manuscript copies dating from before the invention of the printing press. The earth is the centre of Sacrobosco’s model of the universe, with seven ‘planets’ (the moon, Mercury, Venus, the sun, Mars, Jupiter and Saturn in order) arrayed outwards from it. This 1581 print edition of the treatise features two volvelles (wheel charts with moving parts), this one depicting a lunar eclipse.

Volvelle in action from

Johannes de Sacrobosco, Sphaera

Cologne: Maternus Cholinus, 1581

Shelfmark: Bury.SAC.Sph.1581

***

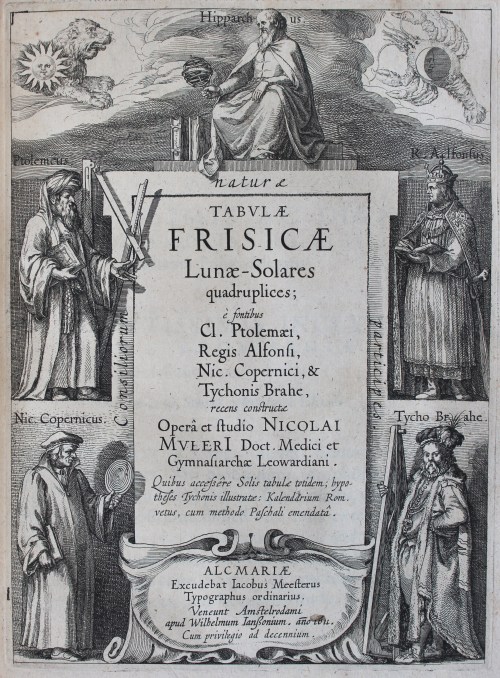

The Dutch astronomer Nicolaus Mulerius’ Tabulae frisicae lunae-solares quadruplices of 1611 is a collection of solar and lunar tables according to the calculations of Ptolemy (2nd century AD), King Alfonso X of Castile (1221-1284), Nicolaus Copernicus (1473-1543) and Tycho Brahe (1546-1601) respectively. The four great astronomers are depicted on the illustrated title page, with their illustrious forefather Hipparchus (2nd century BC) at the head.

Nicolaus Mulerius, Tabulae frisicae lunae-solares quadruplices

Alkmaar: Jacob de Meester, 1611

Shelfmark: Keynes.Ec4.1.3/2

***

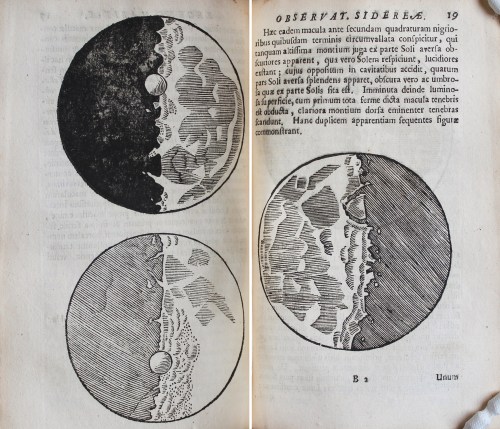

Galileo Galilei’s treatise of 1610 Sidereus nuncius (Sidereal Messenger) was the first published scientific work to draw on the newly invented telescope, called by the Latin word ‘perspicillum’ in Galileo’s text, and contains the astronomer’s observations on the moon and hundreds of formerly unknown stars he had been the first human to witness. Though initially controversial, Galileo found a supporter in Johannes Kepler, who verified Galileo’s findings independently and published his own confirmation of them a few months later. This first London edition of the work, published in 1653, includes Kepler’s Dioptrice, a treatise on the telescope, as an addendum. The illustrations of the lunar surface on these pages are Galileo’s own.

***

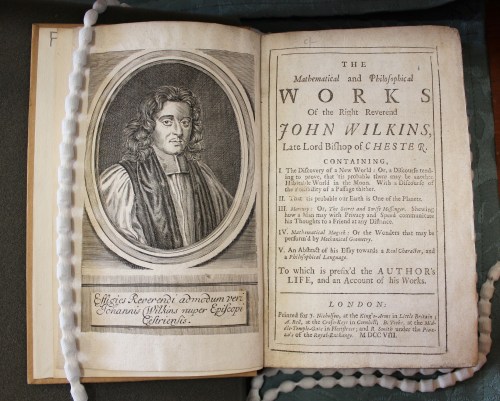

The natural philosopher John Wilkins (1614-1672) was a man of many parts: founder member of the Royal Society, Master of Trinity College, Cambridge, and finally Bishop of Chester. In The Discovery of a World in the Moone, first published in 1638, Wilkins put forward 13 propositions, drawing partly on the recent testimonies of Galileo and Kepler, in support of his theory ‘that the Moone may be a world’, including:

- That the strangenesse of this opinion is no sufficient reason why it should be rejected, because other certaine truths have beene formerly esteemed ridiculous, and great absurdities entertained by common consent

- That a plurality of worlds doth not contradict any principle of reason or faith

- That the Moone hath not any light of her owne

- That as their world is our Moone, so our world is their Moone

These two later editions contain an added fourteenth proposition, ‘That tis possible for some of our posteritie, to find out a conveyance to this other world; and if there be inhabitants there, to have commerce with them’, in which Wilkins suggests various possible methods of moon travel, including hitching a lift on a large winged animal (such as a ‘Ruck’, i.e. the roc, a mythological bird still believed in by many at the time) and inventing a flying chariot.

John Wilkins, The Mathematical and Philosophical Works of

the Right Reverend John Wilkins, Late Lord Bishop of Chester

London: John Nicholson; Andrew Bell; Benjamin Tooke; Ralph Smith, 1708

Shelfmark: Keynes.F.25.15

John Wilkins, A Discourse concerning a New World & Another Planet in 2 Bookes

London: John Maynard, 1640

Shelfmark: Keynes.D.5.69

***

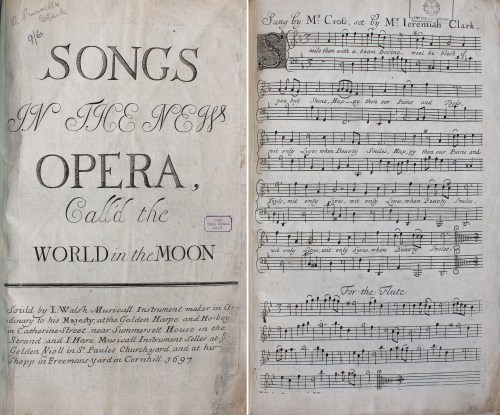

The World in the Moon, a new opera staged in 1697 at the Dorset Garden Theatre in Whitefriars, by the Thames, featured songs by Daniel Purcell (brother of Henry) and Jeremiah Clarke. The opera’s book, by Elkanah Settle, was inspired by The Man in the Moone, a posthumously published narrative work by the Anglican bishop Francis Godwin (1562-1633) that purported to describe a ‘voyage of utopian discovery’ and is now considered one of the first works of science fiction. The stage directions in Settle’s text suggest the production must have been spectacular:

The Flat-Scene draws, and discovers Three grand Arches of Clouds extending to the Roof of the House, terminated with a Prospect of Cloud-work, all fill’d with the Figures of Fames and Cupids; a Circular part of the black Clouds rolls softly away, and gradually discovers a Silver Moon, near Fourteen Foot Diameter: After which, the Silver Moon wanes off by degrees, and discovers the World within, consisting of Four grand Circles of Clouds, illustrated with Cupids, &c. Twelve golden Chariots are seen riding in the Clouds, fill’d with Twelve Children, representing the Twelve Celestial Signs …

This song, ‘Smile then with a beam Devine’, is from the prologue of the opera, and contains a separate flute part at the foot of the page, common in music publications of the time, which could be used either to double the voice or to perform the song as an instrumental piece.

Songs in the New Opera, Call’d The World in the Moon

London: John Walsh; Joseph Hare, 1697

Shelfmark: Rw.85.1/9

***

Moon exploration has been a subject of science fiction for centuries, but properly took off (ha ha) in the 19th century with works such as Edgar Allan Poe’s short story ‘The Unparalleled Adventure of One Hans Pfaall’ (1835) and Jules Verne’s From the Earth to the Moon (1865).

This radical political pamphlet of 1820, ‘The Man in the Moon’, by the satirist William Hone, employs the conceit of a man travelling to the nation of ‘Lunataria’:

I lately dream’d that, in a huge balloon,

All silk and gold, I journey’d to the Moon,

Where the same objects seem’d to meet my eyes

That I had lately left below the skies …

The resemblance of Lunataria to his home planet enables Hone to pass comment on the political events of the day, including on the left the Peterloo Massacre of 1819. The illustration on the right shows the Army, the Church, the Prince Regent and the devil linked in dance, in a parody of the Holy Alliance that arose in Europe following the fall of Napoleon. The illustrator is George Cruikshank, who was later a friend of Charles Dickens and provided illustrations to his early novels.

***

The most enduring creation of the illustrator Jan Pieńkowski (1936-2022, KC 1954) was the Meg and Mog series of books, which he wrote over a period of more than 40 years in collaboration first with the author Helen Nicoll and, after her death in 2012, with his partner David Walser. Meg on the Moon, an early entry in the series, tells the story of the witch Meg and her cat Mog going to the moon for Mog’s birthday treat.

GB