In November 2024 King’s College had the opportunity to host the annual doctoral and postdoctoral research conference “Dante Futures 2024: New Voices in the UK and Ireland”. For this occasion, an exhibition of rare early printed and manuscript materials relating to Dante was mounted in the library. As this year marks the 760th anniversary of Dante’s birth in 1265, we thought it would be timely to share some of these treasures in an online exhibition.

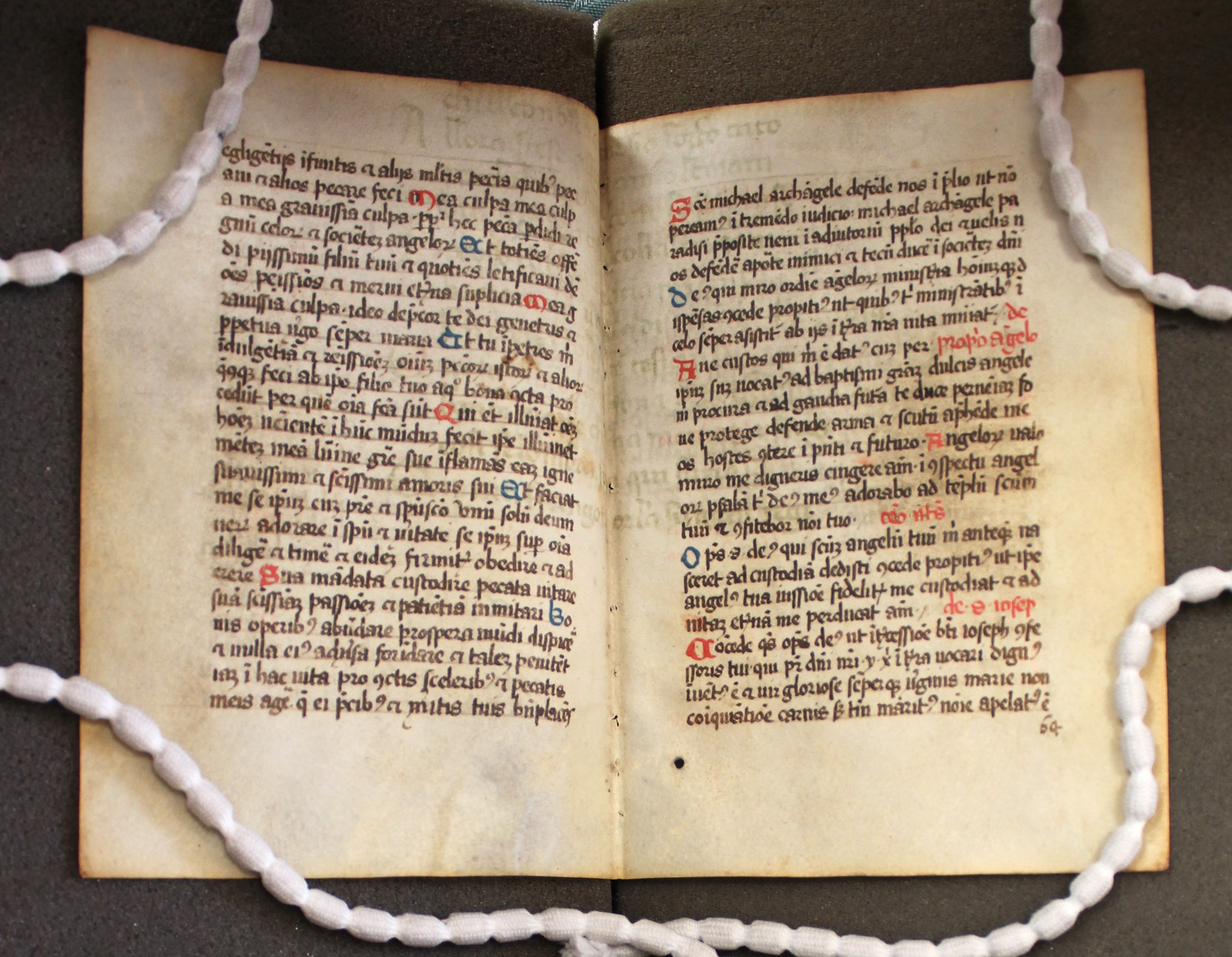

While there is no extant autograph manuscript of the Divine Comedy, many other fourteenth- and fifteenth-century manuscripts survive. Below is a fifteenth-century breviary written in an Italian hand on vellum. This is a palimpsest, namely a manuscript on which a piece of writing has been superimposed, effacing the original text. In this case the erased text is from Dante’s Inferno, one of the three parts of the Divine Comedy, which was written on at least 31 leaves used in this breviary. The vellum was not thoroughly cleaned when it was prepared for reuse, meaning Dante’s text can be seen by the naked eye in a number of places, apparently written in a fourteenth-century hand. Each leaf of the original manuscript was folded in two, vertically, to create two leaves (one bifolium). At the top of the page we can see lines 39-40 of Inferno VIII (spelling modernised):

ch’i’ ti conosco, ancor sie lordo tutto.

Allora [di]stese al legno ambo le mani

[for thee I know, all filthy though thou be.

Then toward the boat he stretched out both his hands]

Breviary (imperfect), fifteenth century, partly written on a palimpsest vellum of Dante’s Inferno, fourteenth century (Salt MS 3)

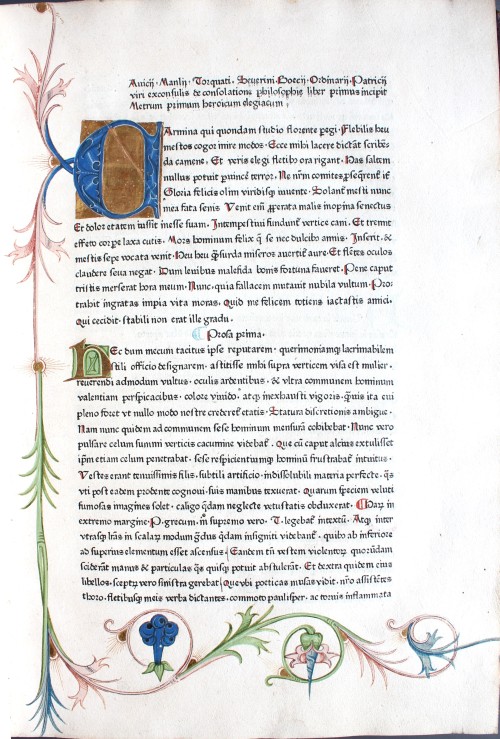

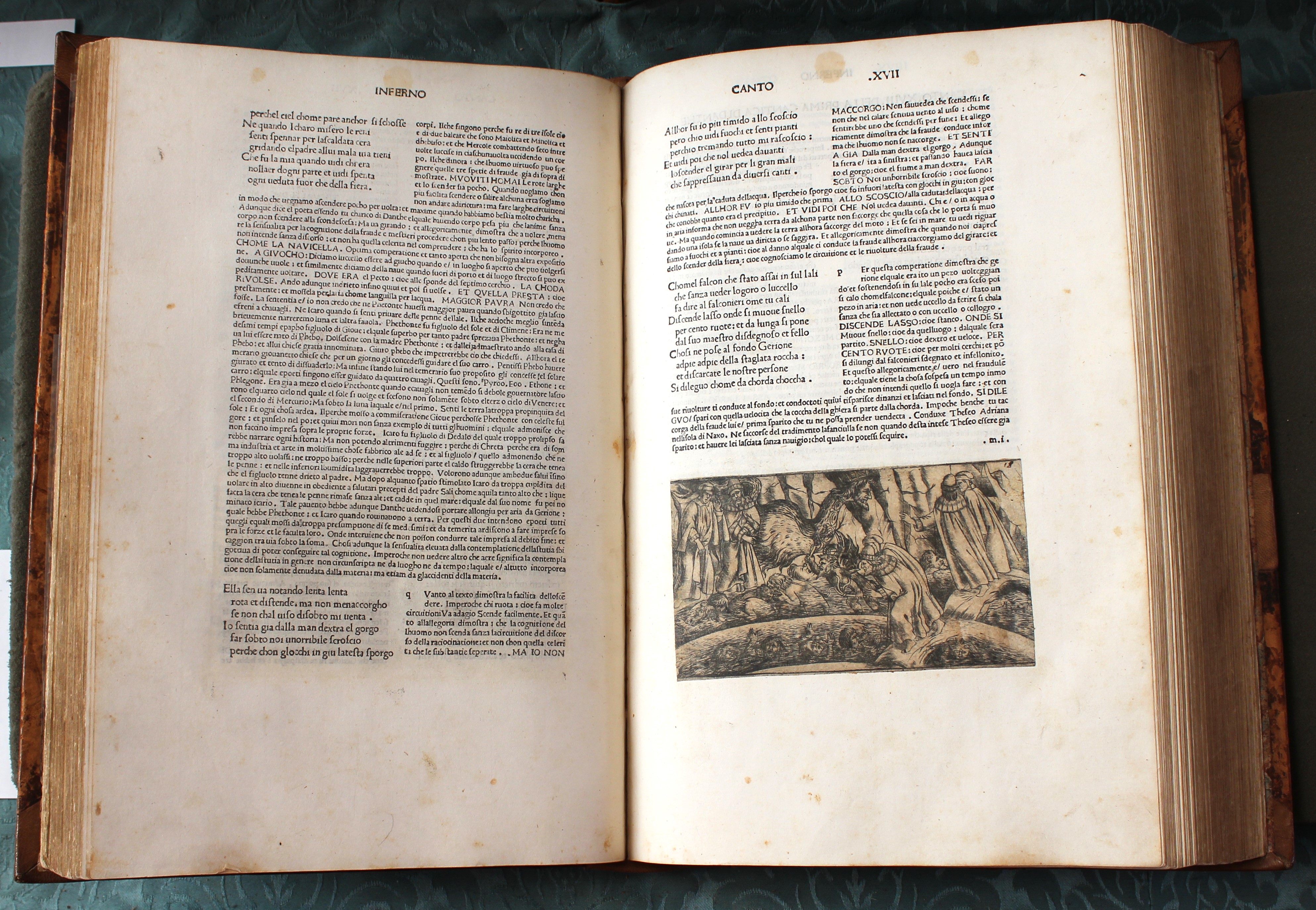

The first printed edition of the Divine Comedy appeared in 1472. This incunabulum from 1481 (a book from the dawn of printing, printed before 1501) includes the commentary of Cristoforo Landino with additions by Marsilio Ficino, and is the third edition of the work to be published. The engravings are attributed to Baccio Baldini after designs by Sandro Botticelli, eighteen of which are included in this copy, mainly pasted in spaces left by the printer for that purpose. Here we see the descent of Virgil and Dante into Hell, as they move to the circle of the fraudulent in the Malebolge, thanks to the mythological monster Gerion, who flies them down on its back. With the face of a just man, the body of a snake, the tail of a scorpion, and hairy paws, Gerion is an allegory of falseness and fraud, precisely because its human face displays a benign humanity while the serpentine and monstrous body reveals its evil:

Comento di Christophoro Landino fiorentino sopra

La comedia di Danthe Alighieri poeta fiorentino

(Florence: Nicholo di Lorenzo della Magna, 1481; Bryant.XV.1.4)

Aldus Manutius (c. 1449/1452–1515), founder of the Aldine Press in Venice, was one of the most important printers of the period. He was an advocate of the smaller, more portable book format, which is arguably the precursor to the modern paperback. His work also helped to standardise the use of punctuation.

Along with Greek classics, the Aldine Press also printed Latin and Italian works. At the start of the sixteenth century the Bembo family—a noble Venetian family—hired the Aldine Press to produce accurate texts of both Dante and Petrarch using Bernardo Bembo’s personal manuscript collection. Pietro Bembo worked with Manutius from 1501 to 1502 to undertake this work, resulting in this, the fifth edition of the Divine Comedy to be published. Here we see the well-known dolphin-and-anchor printer’s device used by the Aldine Press, adopted in 1502 and used for the first time in this publication:

Dante Alighieri, Lo ‘nferno e ‘l Purgatorio e ‘l Paradiso di Dante Alaghieri

(Venice: Aldus Manutius, 1502; M.71.15)

The Aldine Press published a second edition of the Divine Comedy in 1515 in partnership with Aldus’s father-in-law, Andrea Torresani “nelle case d’Aldo et d’Andrea di Asola suo suocero” (at the house of Aldo and Andrea of Asola, his father-in-law), with whom he had a professional relationship from 1506 until his death in 1515. Although the volume appeared just after his death, Aldus is believed to have prepared this second edition himself. The publication was dedicated to Vittoria Colonna (1490–1547), one of the most famous women of the Italian Renaissance, friend to the most important cultural figures of the age including Bembo, Castiglione and Michelangelo, and a poet in her own right. Below is the opening of the second part of the Divine Comedy, the Purgatorio:

Dante col sito, et forma dell’inferno tratta dalla istessa descrittione del poeta

(Venice: nelle case d’Aldo et d’Andrea di Asola suo suocero, 1515; Keynes.Ec.7.3.22)

Alessandro Vellutello (born 1473) produced an influential commentary on the Divine Comedy, published in 1544, which is a real gem in the collection of rare books bequeathed to King’s College by novelist E.M. Forster (1879–1970). This copy belonged to Bishop John Jebb (1775–1833) who gifted it to Forster’s grandfather, Charles Forster (1789–1871). The printer left spaces for 87 woodcut illustrations which were first used in this edition and subsequently in a number of other editions throughout the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. They were considered some of the most beautiful Renaissance illustrations of the poem after Botticelli’s.

This is a depiction of Giudecca (named after Judas Iscariot), the very last region of Hell. The sinners are punished by being completely frozen in the lake of Cocytus, some upright, some upside down, some with their bodies bent double. Enormous in size, we see the top half of Lucifer in the lake, gnawing on the bodies of sinners:

La comedia di Dante Aligieri con la nova espositione di Alessandro Vellutello

(Venice: per Francesco Marcolini, 1544; Forster.DAN.Com.1544)

Cosimo Bartoli (1503–72) was a humanist, philologist and writer. He promoted the Italian vernacular as a language which could be used in scientific discussion as much as Latin, and Dante was regarded as an example of the heights the vernacular could reach. A friend of the famed Renaissance painter and architect Giorgio Vasari (1511–74), he also worked for the Medicis for most of his life. His Ragionamenti accademici sopra alcuni luoghi difficili di Dante takes the form of fictitious discussions held between Bartoli and his Florentine friends, to provide explanations of some of the most difficult passages in the Divine Comedy. A collection of some of the lectures he had given in the Accademia fiorentina between 1541 and 1547, it was published in Venice in 1567:

Cosimo Bartoli, Ragionamenti accademici di Cosimo Bartoli gentil’huomo et

accademico fiorentino sopra alcuni luoghi difficili di Dante

(Venice: appresso Francesco de Franceschi Senese, 1567; Bury.BAR.Rag.1567)

JC/IJ