While Ridley Scott’s biopic Napoleon has come and gone without too much fanfare or recognition during awards season, its release nevertheless reminded me that we have a volume in our rare-book collection that belonged to the French emperor, whose 255th birthday falls today (15 August 1769 – 5 May 1821):

Title page of Pierre Victor Jean Berthre de Bournisseaux, Histoire des guerres de la Vendée et des Chouans, depuis l’année 1792 jusqu’en 1815 (Paris: Claude Brunot-Labbe, 1819; M.37.116)

Napoleon’s ink signature is above the circular stamp: “l’Empereur Napoleon”. As he had been in exile on St Helena since October 1815, the book must have been shipped to him from France. The volume was sold at auction by Sotheby’s in June 1905 and was later donated to the College by Kingsman Alban Goderic Arthur Hodges (1893-1982):

Rear pastedown on which is stuck an advertisement for the Sotheby’s sale on 1-3 June 1905, including “Books from the library of the Emperor Napoleon I at St. Helena”. Next to it is a slip describing this book and its provenance: “Cachet of St. Helena and ‘L’Empereur Napoléon’ on title”.

While there are several items in King’s College’s collection that belonged to British monarchs, these are usually identified as such thanks to a royal cypher or a crest on the binding. This copy of the order of service performed at the coronation of George II (1727) belonged to his grandson George III (1738-1820), who was on the throne during Napoleon’s reign and exile:

The Form and Order of the Service that Is To Be Performed […] in the Coronation of their Majesties, King George II. and Queen Caroline (London: John Baskett, 1727; Thackeray.M.32.53)

The volume is bound in red morocco featuring an elaborate gilt panel design on front and rear boards with the crest of King George III at the centre and royal cyphers on each corner. This book did not come to King’s College as part of the large Thackeray Bequest, but was purchased in 1950. Though George III’s pre-1801 crest was identical to that of George II, the fact that Provost George Thackeray was chaplain in ordinary to George III suggests that he likely received it as a gift from the latter (who may have inherited it from his grandfather George II).

Gone are the days of gilt imperial bindings for the erstwhile French emperor: Napoleon can now only assert his ownership through a mere signature, like most other book owners. The contrast between the British monarch’s mark of ownership through this elaborate morocco binding and Napoleon’s ink inscription on the title page could not be starker.

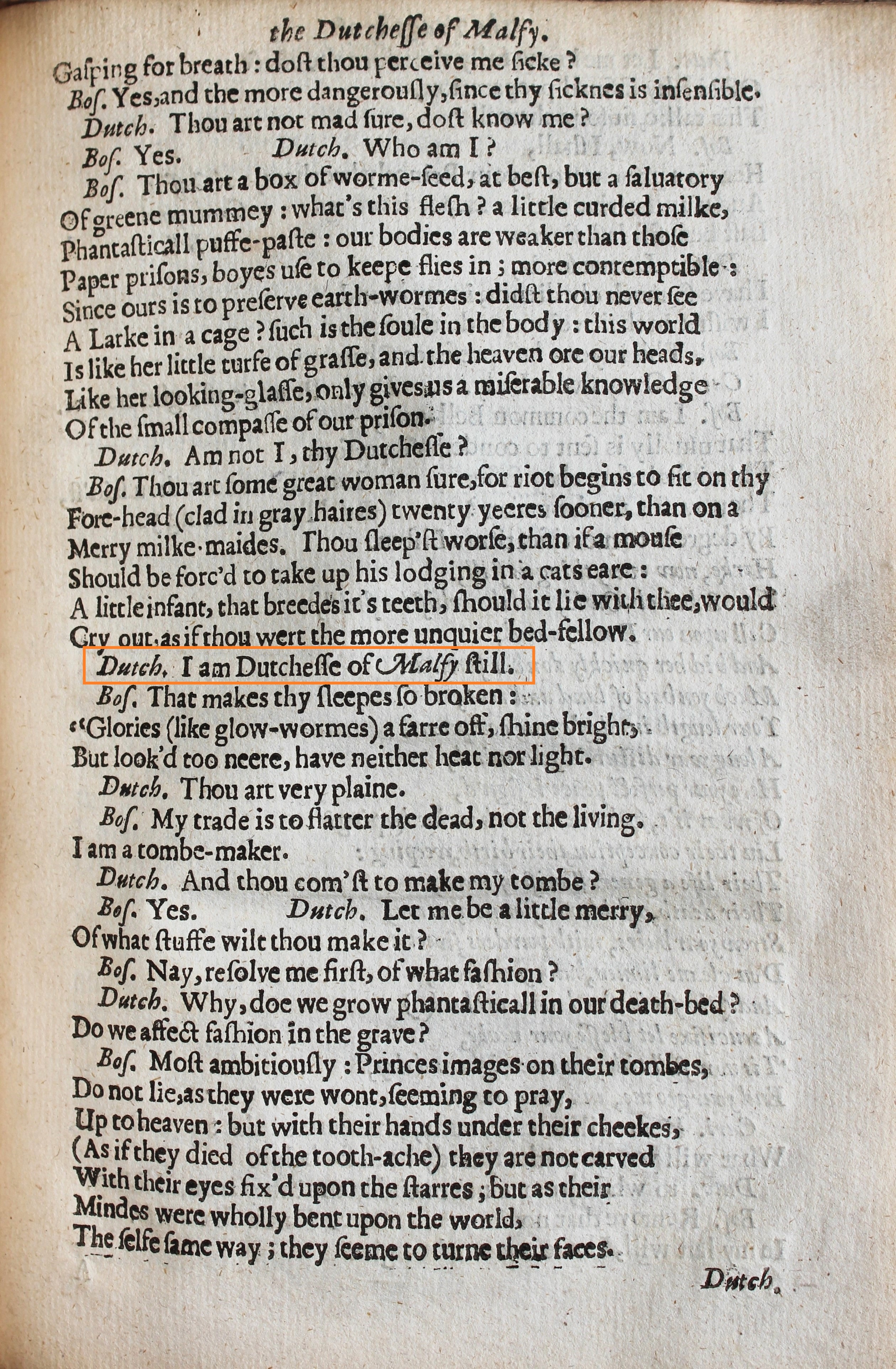

One cannot help but draw a parallel between Napoleon’s predicament and that of the heroine in John Webster’s play The Duchess of Malfi (1623), loosely based on the life of Giovanna d’Aragona, Duchess of Amalfi (1478-1510):

Title page of the second edition of John Webster’s The Dutchesse of Malfy: A Tragedy (London: John Raworth and John Benson, 1640; Keynes.C.6.27)

In the play, the widowed duchess secretly marries her lowly household steward Antonio and bears him three children, thus attracting the rage of her two brothers Ferdinand and the Cardinal who want to safeguard their inheritance. The duchess and her two younger children are murdered at Ferdinand’s behest in the fourth act. As she is about to be strangled by the executioners, she utters the famous words, “I am Duchess of Malfi still”:

There is a sense of poignancy in the defiance shown by both the duchess and Napoleon as they cling to a former glorious past in the face of imminent death or a fall from grace. The difference is that Napoleon was technically no longer an emperor in 1819, while the duchess was still Duchess of Malfi, at least in name, when she died. In November 1818, Napoleon had been informed that he would remain a prisoner on St Helena for the rest of his life, and the island’s governor Sir Hudson Lowe had refused to recognise him as a former emperor. However, as this ownership inscription confirms, “Napoleon never considered forgoing ceremony or the recognition of his title. It was the only way he could assert his claim to being emperor in the face of the British insistence that he was a simple general. Much of his stay on St Helena was about constructing a space for himself in which he displayed his quality as an imperial sovereign”.[1]

IJ

Notes

[1] Philip Dwyer, Napoleon: Passion, Death and Resurrection, 1815-1840 (London: Bloomsbury Publishing, 2019, pp. 44-45)