In honour of the Year of the Dragon, we went on a perilous mission into the Library’s treasure hoards of books to find out if any of those fearsome beasts might be lurking inside. Alas, no Chinese dragons were discovered, but we did encounter several of the European variety and bravely captured their images to share with you in this post.

Our first dragon however, is not to be found within the pages of a book. It is a much more solid beast; a sculpture which originally adorned the College Chapel, but which was removed and replaced during restoration work. For the last few decades it has stood guard over the upstairs entrance of our Library, somewhat worn and battered by time maybe, but fierce and stalwart nonetheless.

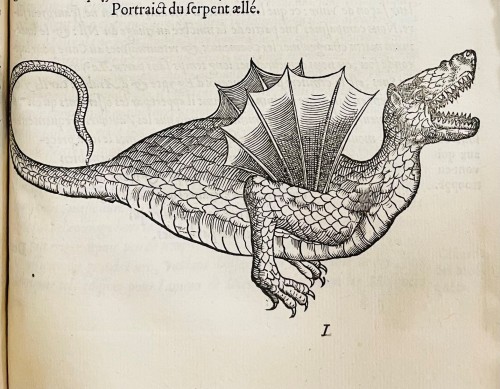

Several sixteenth-century works from our collections proved to be harbouring dragons. The first image comes from a volume of natural history by Pierre Belon (1517?-1564), originally produced in 1553. This is a very early printed depiction of a dragon with wings. Belon, a French naturalist and traveller, claimed to have seen embalmed bodies of these creatures during his travels in Egypt.

Egyptian dragon from Les Obseruations de plusieurs singularitez & choses memorables by Pierre Belon, Paris, 1555 (T.16.20)

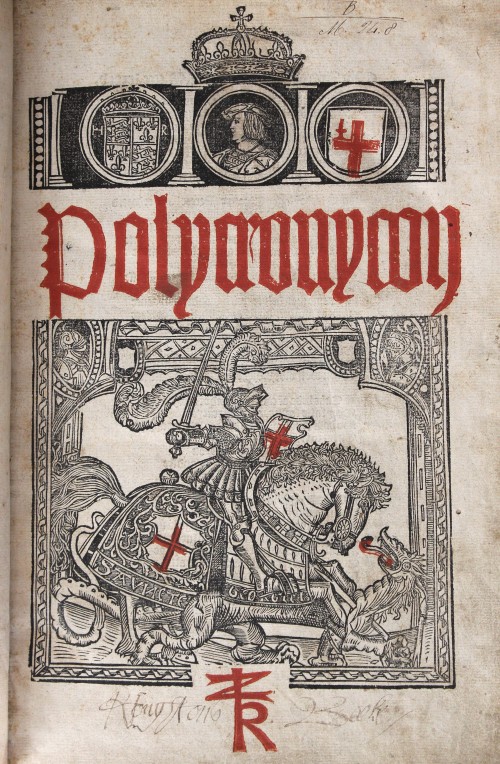

Secondly, we have an illustration depicting a very grand St George slaying a dragon, which adorns the title page of the 1527 edition of Polycronicon, by Benedictine monk, Ranulf Higden (ca. 1280-1364). This was a very popular work of world history, written originally in Latin and later translated into English and added to over the following centuries.

St George and the dragon from the title page of Polycronycon by Ranulf Higden, London, 1527 (M.24.08)

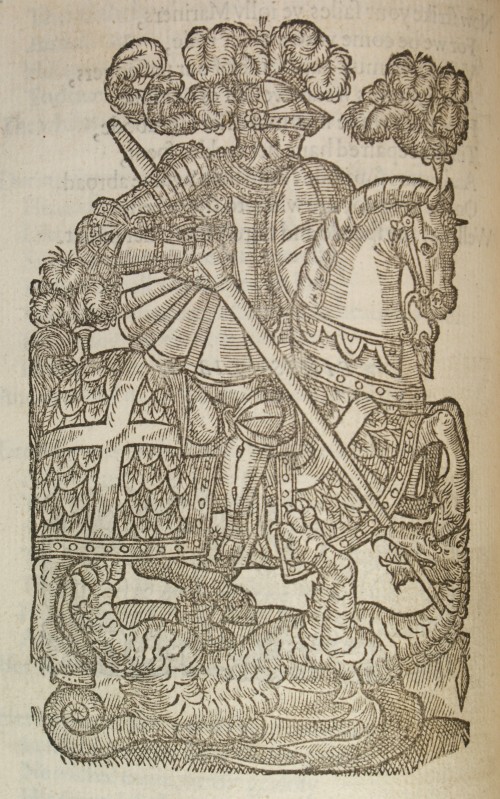

Our last sixteenth-century image is from a 1590 edition of Edmund Spenser’s Faerie Queene. Here we have another knight, the Redcrosse Knight, killing a dragon in a very similar fashion. The Redcrosse Knight is very closely associated with St George.

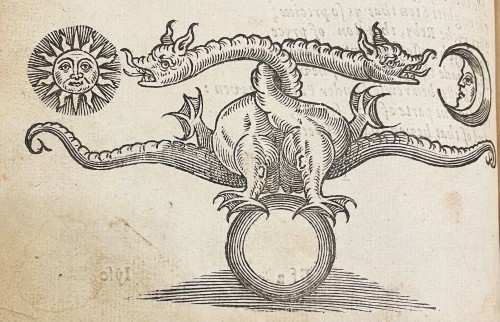

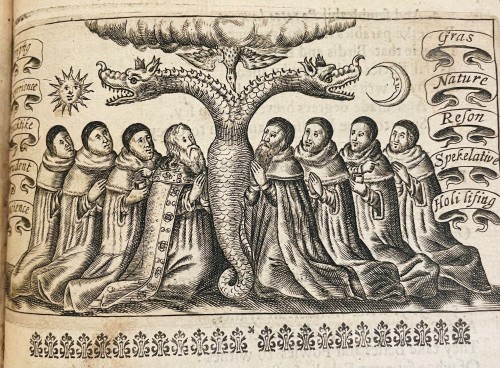

Moving into the seventeenth century, a work of alchemy provides more images. Dragons in alchemy symbolize the unification of opposing forces like the sun and the moon or sulphur and mercury, and the change they produce when combined. We therefore get these striking illustrations of entwined or two-headed dragons, as shown in the images below.

Alchemical dragon symbol from page 212 of Theatrum Chemicum Britannicum edited by Elias Ashmole, London, 1652 (Keynes.C.4.2)

Two-headed dragon from page 213 of Theatrum Chemicum Britannicum edited by Elias Ashmole, London, 1652 (Keynes.C.4.2)

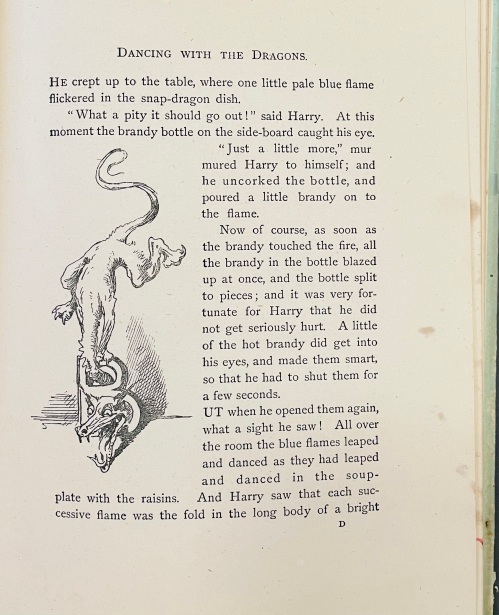

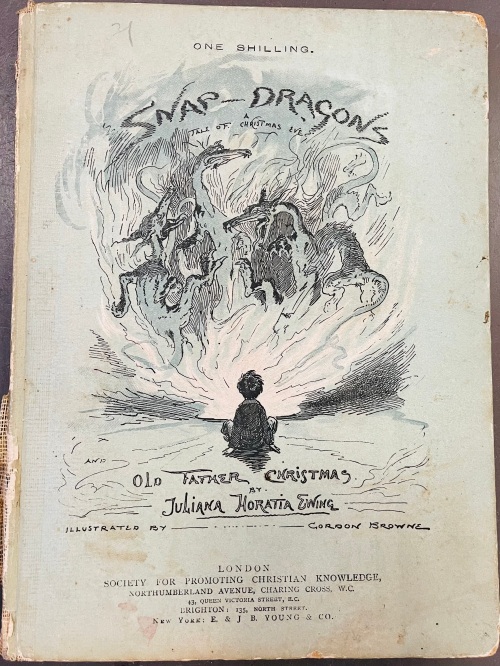

From our collection of children’s books comes a tale brimful of dragons. Snap-dragons: a Tale of Christmas Eve by Juliana Horatia Ewing (1841-1885) revolves around the parlour game of Snap-dragon, very popular in the nineteenth century, in which people took it in turns to snatch raisins from a bowl of flaming brandy. This particular game conjures up a bevy of real dragons who draw a little boy into their boisterous and violent game of trading insults, or “snapping” at each other. It has some delightful illustrations.

Cover of Snap-dragons: a Tale of Christmas Eve by Juliana Horatia Ewing, London, 1888 (Rylands.C.EWI.Sna.1888a)

Finally, we have this charming little dragon wrapped around an initial letter A in a volume of fairy tales, also by Ewing. Oddly enough, the tale it accompanies: “Knave and Fool”, features no dragons at all.

Initial dragon from Old-fashioned Fairy Tales by Juliana Horatia Ewing, London, [1882?] (Rylands.C.EWI.Old.1882)

References

Mythical creatures at the Edward Worth Library: Here be dragons! [accessed January 2024]

Jean Chevalier and Alain Gheerbrant, A Dictionary of Symbols. Oxford, 1994.

Lyndy Abraham, A Dictionary of Alchemical Imagery. Cambridge, 1998.

AC