This year marks both 200 years of the modern railway and the 180th anniversary of the opening of Cambridge Station on 29 July 1845. These anniversaries prompted us to search out and share some railway-related material from our various special collections. Enough material was found for two blog posts, so this first will begin close to home with Cambridge, whilst a second subsequent post will range further afield.

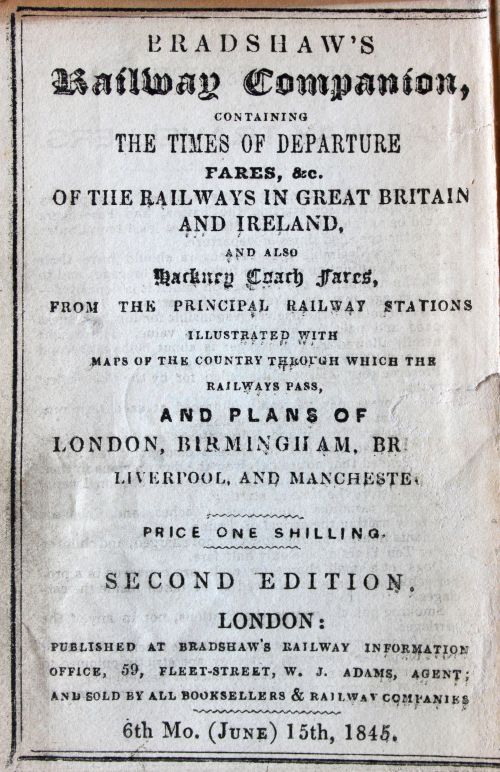

We happen to hold both a Cambridge guidebook published in 1845 and an edition of Bradshaw’s Railway Companion from the same year, both of which anticipate the imminent arrival of the station.

Bradshaw’s guides were the first railway timetables ever to be published and were hugely popular in the Victorian era. They are frequently referenced in the literature of the day, including in Arthur Conan Doyle’s stories of Sherlock Holmes. Our copy dates from June 1845, when the closest station to Cambridge was Bishop’s Stortford, but the timetable below is already labelled as: “Eastern Counties – Cambridge Line”.

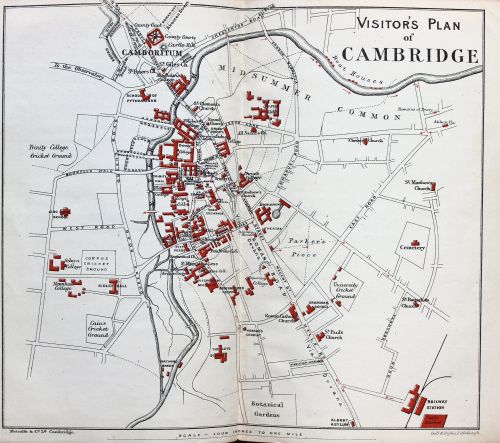

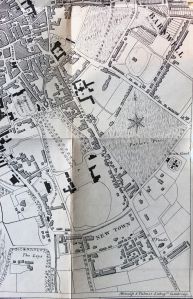

The Cambridge Guide published the same year has a map which already includes directions to the station, although the travel information provided at the rear of the guide still focuses on describing the numerous stagecoach routes between Cambridge and London. Many of these coaches travelled via the station at Bishop’s Stortford, presumably in order to provide onward travel to Cambridge for rail passengers alighting there.

Section of the folded city map from The Cambridge Guide. The road in the bottom right-hand corner is labelled as leading to the station

In the course of describing the wider region, this guide explains that:

A rail-road is now in rapid progress from London by Cambridge, and extending by Brandon to Norwich; a branch is also contemplated from Ely to Peterborough, and so to the north of England.

Bradshaw’s Railway Companion also provides an interesting insight into the rules of the early railway. These include the very modern sounding prohibition: “Smoking not allowed at the Stations, nor in any of the carriages”. This rule was in force across much of the rail network until Parliament passed a law in 1868 mandating that every train must have a smoking compartment.

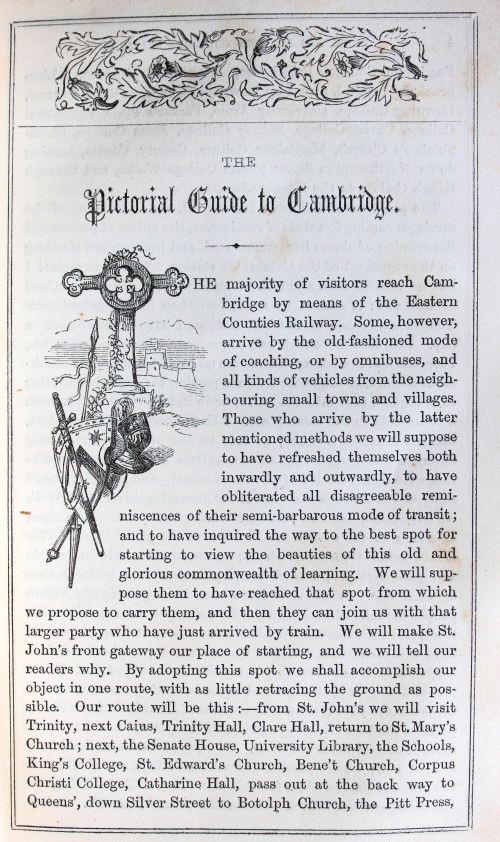

Once Cambridge station was open it soon became the natural starting point for many descriptive tours of the city, on the justified assumption that the majority of tourists would now choose to arrive by rail. The first paragraph of The Pictorial Guide to Cambridge, which adopts a very informal, discursive tone, states this clearly, and the author even disparages other forms of transport:

The majority of visitors reach Cambridge by means of the Eastern Counties Railway. Some, however, arrive by the old-fashioned mode of coaching, or by omnibuses … Those who arrive by the latter mentioned methods we will suppose to have refreshed themselves both inwardly and outwardly, to have obliterated all disagreeable reminiscences of their semi-barbarous mode of transit …

The Pictorial Guide goes on to hymn the glories of the new station and the convenience of rail travel:

… here we are standing on the pavement of the Cambridge station. What a surprise! I had no idea of such a length of building, all covered over, and comfortable; it cannot be much less than four hundred feet. This really is one of the best stations I have seen for many a day. But, how is it that the stream of passengers are dividing? Oh, I see, one half are taking themselves off to that handsome refreshment room, and the other half are passing through the building to trudge on foot into the town, or to indulge themselves with a cheap ride to the same place.

You see the advantage of travelling by rail; whilst we breakfasted at home, and have come all this distance as fresh and clean as when we started, there are those less fortunate folks who left their homes by day-break this morning and arrived an hour ago, have hardly had time to make their first meal, and cannot possibly turn out in half such good trim as ourselves.

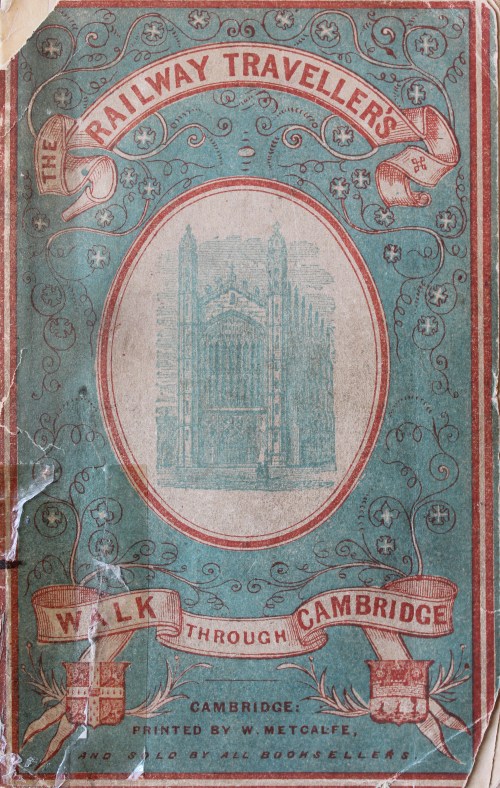

Another guidebook, from 1863, explicitly markets itself to rail passengers by using the title The Railway Traveller’s Walk through Cambridge. The station was completely remodelled in that year and the guide remarks approvingly that: “It now forms one of the finest on the line”. Naturally, King’s College Chapel is depicted on the guide’s cover.

A later edition of this guidebook from the 1890s, reissued under a different title, contains a useful fold-out map of the city, in which important buildings and the station are highlighted in red.

By this final decade of the nineteenth century, writers were already reminiscing about the privations of the early days of the railways, as can be seen in the amusingly titled guidebook A Gossiping Stroll through the Streets of Cambridge. The author, S.P. Widnall, recalls using an umbrella to keep off the rain when travelling in a second class carriage that had no glass in its windows!

Title page of A Gossiping Stroll Through the Streets of Cambridge, by S.P. Widnall, Cambridge, 1892. Classmark: NW CAM 3ML Wid

Widnall also discusses the effect of the railway upon coaching routes between London and Cambridge, stating that:

When the railway was finished to Cambridge the coaches were of course driven off the road. Some people professed to dislike railways and to prefer riding behind four horses; this led to the attempt to keep one coach on the road, and for a short time the Beehive continued its journeys, when it arrived for the last time it was draped in black, as mourning for its own decease.

Additionally, he touches upon the location of the station, which is (and remains today) some way out of the city centre, remarking that:

We believe the Station would have been nearer the town had it not been opposed by the University authorities on account of the supposed disturbance to University pursuits.

Some modern histories of the Cambridge railway dismiss this as a myth, asserting that the area to the west of the eventual site was already too heavily built up for a more centrally located station to be either economically or practically feasible. Nevertheless, the belief that the University was to blame persists to this very day, especially among those who trudge wearily to the station every evening after work!

AC

References and further reading:

Reginald B. Fellows, London to Cambridge by Train 1845 – 1938, Cambridge, 1939

Cambridge: its Railways and Station [accessed September 2025]

Railway 200 [accessed September 2025]