As the Lunar New Year of the Snake gets underway, we’ve discovered that our rare book stores are teeming with these sinuous reptiles! They slither through the pages of bibles, travel books, natural history books, works of heraldry and more! Where is St. Patrick when you need him! What follows is a only a selection of the many serpents that have recently emerged, hissing, into the light of day.

It seems appropriate to begin in China, with an illustration from a book on the country by Athanasius Kircher (1602-1680). Kircher was a German Jesuit and Renaissance polymath, who has been styled by some as the last man who knew everything. He had a long eventful life during which he published around forty books on a wide variety of topics, including ancient languages, music and geology. He was refused permission to become a missionary in China himself, but compiled the reports of many of his Jesuit colleagues to produce a magnificently illustrated volume on the country, encompassing zoology, geography, religion, botany, and much more besides. Below is one of the illustrations, featuring two large snakes, and a man in the corner apparently about to attack them with a stick!

Illustration from page 81 of China Monumentis by Athanasius Kircher, Amsterdam, 1667 (Shelfmark: M.40.28)

From one of our early printed bibles comes this woodcut of Adam and Eve in the Garden of Eden, with the wily serpent coiled around a tree in the background. If you look closely, it appears to have a Mohican haircut!

Woodcut from fol. 1 of Biblia cum concordantiis veteris et novi testamenti et sacrorum canonum, London, 1522 (Shelfmark: Keynes.E.12.15)

A later depiction of Eden is found in one of our copies of John Milton’s epic poem Paradise Lost, which has glorious illustrations by Francis Hayman (1708-1776), one of the founding members (and first librarian) of the Royal Academy. Here, in an engraving placed at the beginning of Book 10, the serpent lurks in the corner while Adam and Eve beg forgiveness from God for their disobedience in eating the apple.

Plate facing page 221 of volume 2 of The Poetical Works of John Milton, London, 1761 (Shelfmark; Thackeray.J.60.19)

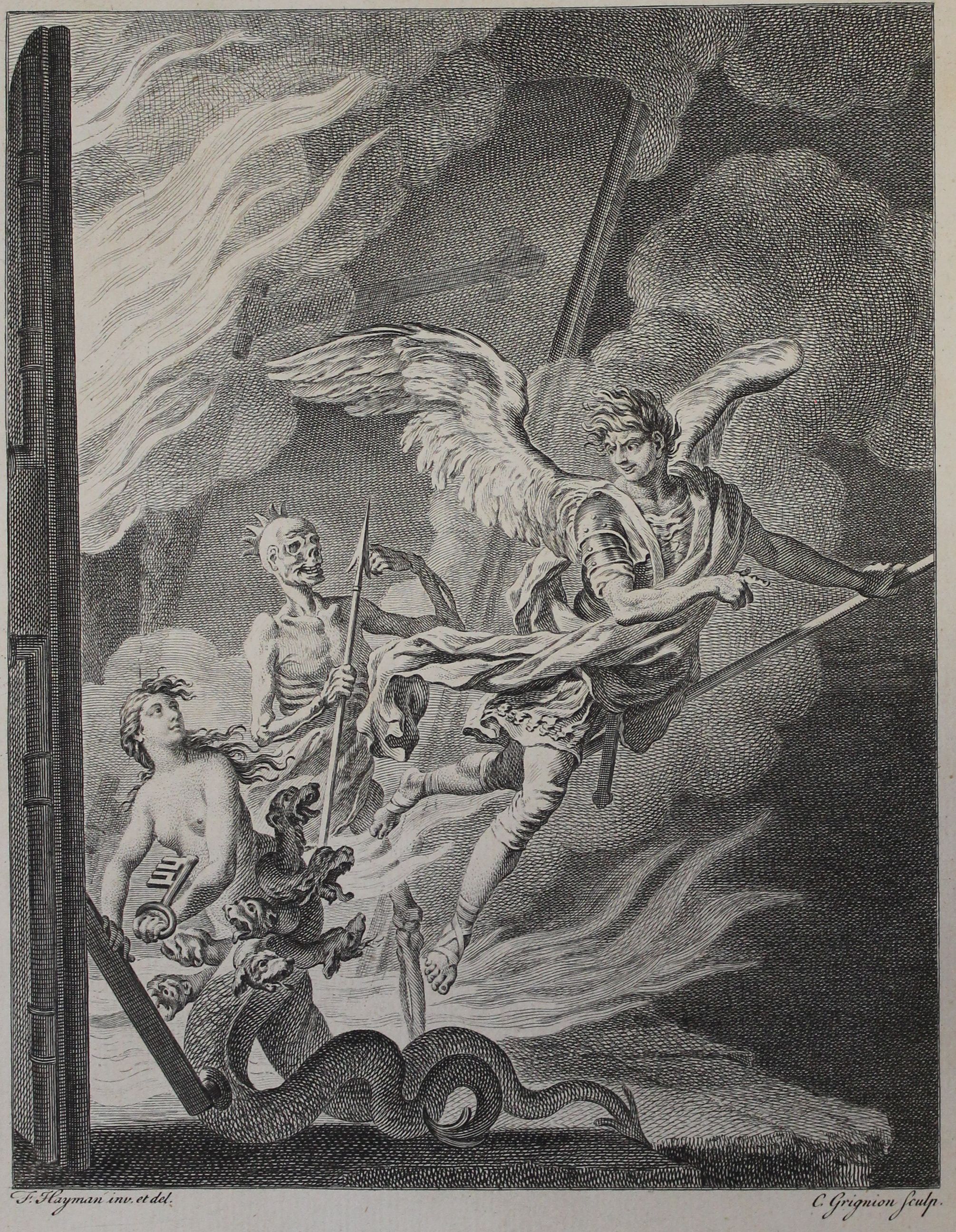

An earlier engraving from Book 2 of the same poem shows Satan at the gates of Hell, which are guarded by a skeletal figure in a crown, a many-headed hell hound, and a woman representing sin, who has a serpent’s coils instead of legs. The text describes it thus:

The one seem’d Woman to the waste, and fair [line 650]

But ended foul in many a scaly fould

Voluminous and vast, a Serpent arm’d

With mortal sting: about her middle round

A cry of Hell Hounds never ceasing bark’d

Plate facing page 83 of volume 1 of The Poetical Works of John Milton, London, 1761 (Shelfmark; Thackeray.J.60.18)

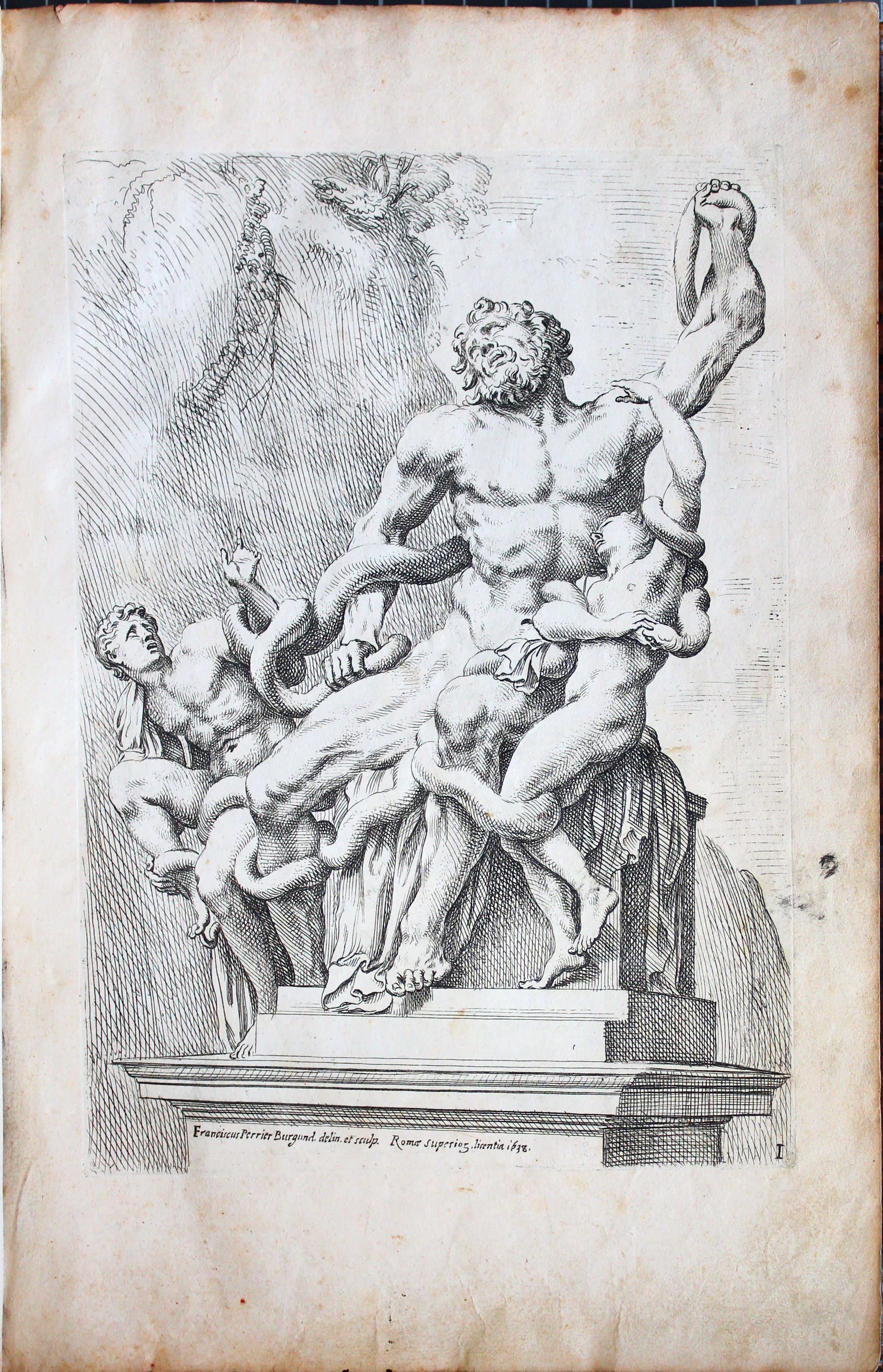

Next we turn to classical mythology and the story of Laocoön, a Trojan priest, who, along with his two sons, was attacked by venomous sea serpents. Reasons given for the attack vary, but Virgil’s version of the story goes that Laocoön was punished for attempting to alert Troy’s inhabitants to the grave threat posed by the Trojan Horse. From the Bury Collection, this seventeenth-century volume of sketches of classical statues includes a rendering of a Roman statue of Laocoön and his sons languishing in the coils of the serpents.

Plate 1 from Segmenta nobilium signora et statuarum by François Perrier, Rome, 1638 (Shelfmark: Bury.PER.Seg.1638)

Another engraving in the same volume depicts a statue of a Vestal virgin, with a snake draped over her shoulder.

Plate 65 from Segmenta nobilium signora et statuarum, by François Perrier, Rome, 1638 (Shelfmark: Bury.PER.Seg.1638)

Snakes are among the many different creatures that appear in printers’ marks or devices, which were a kind of early logo or copyright mark commonly found on the title pages of early printed books. Below is the printer’s device of William Jaggard (1569-1623), which features the ancient Ouroboros symbol of a coiled snake devouring its own tail.

Printer’s device from the title page of The Two Most Unworthy and Notable Histories Which Remaine Unmained to Posterity, by Sallust, London, 1609 (Shelfmark: Keynes.D.2.14)

In heraldry, snakes have often been used on coats of arms as symbols of prudence and subtlety, as this seventeenth-century book, A Display of Heraldrie by John Guillim (1565-1621) explains. Guillim was an antiquarian and officer of arms at the College of Arms in London. His book references the Medusa myth, and notes a belief that if the hair of a woman is placed in manure it will transform into venomous snakes!

Illustration and text from page 153 of A Display of Heraldrie by John Guillim, London, 1611 (Shelfmark: H.17.39)

Later in the same book, an adder wrapped round a pillar is said to symbolize prudence combined with constancy.

Illustration and text from page 213 of A Display of Heraldrie by John Guillim, London, 1611 (Shelfmark: H.17.39)

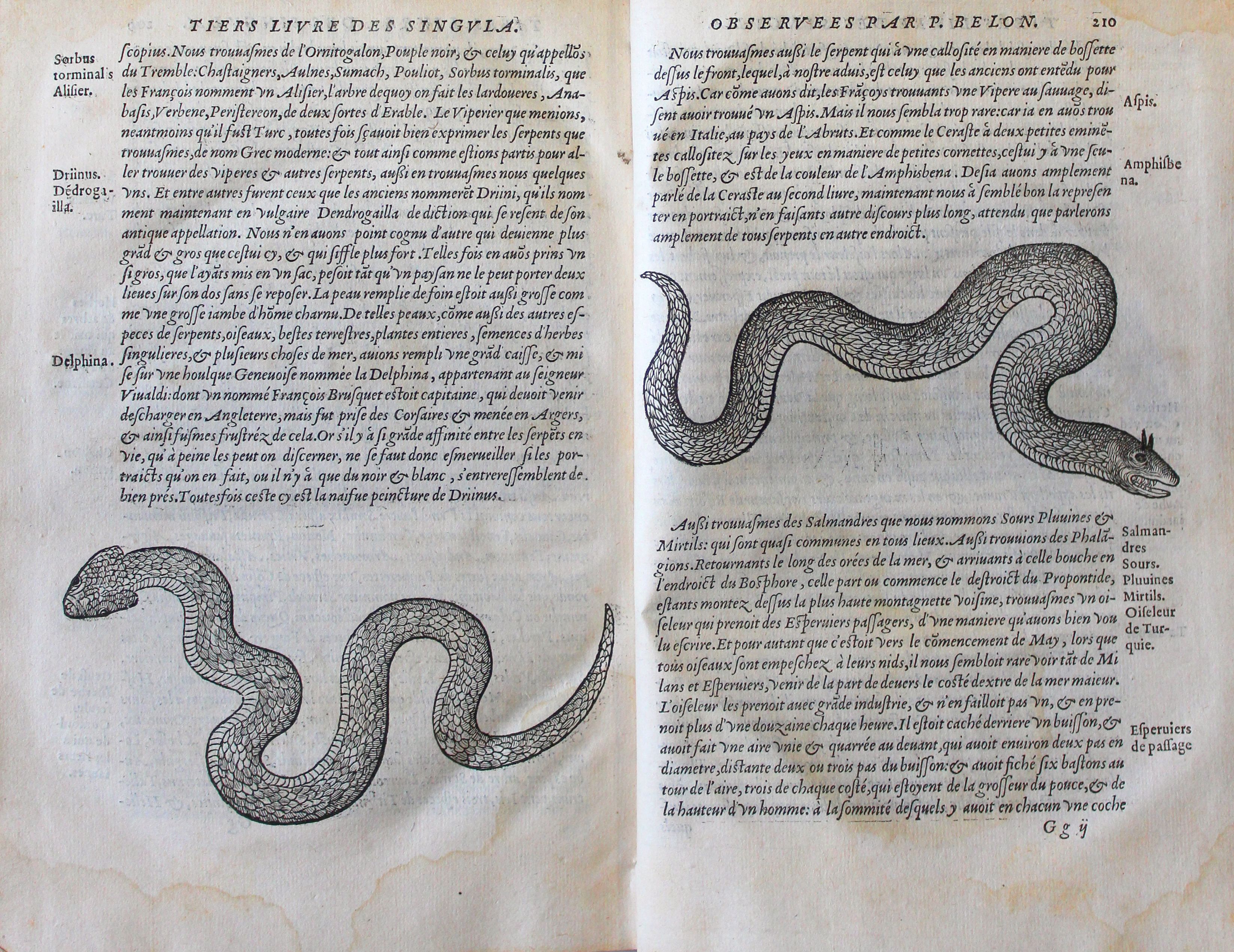

Moving into early works of natural history, we find an abundance of snakes. The sixteenth-century drawings below come from a work published by the traveller and naturalist Pierre Belon (1517?-1564).

Illustrations of snakes from pages 209 and 210 of Les Obseruations de plusieurs singularitez & choses memorables by Pierre Belon, Paris, 1555 (shelfmark: T.16.20)

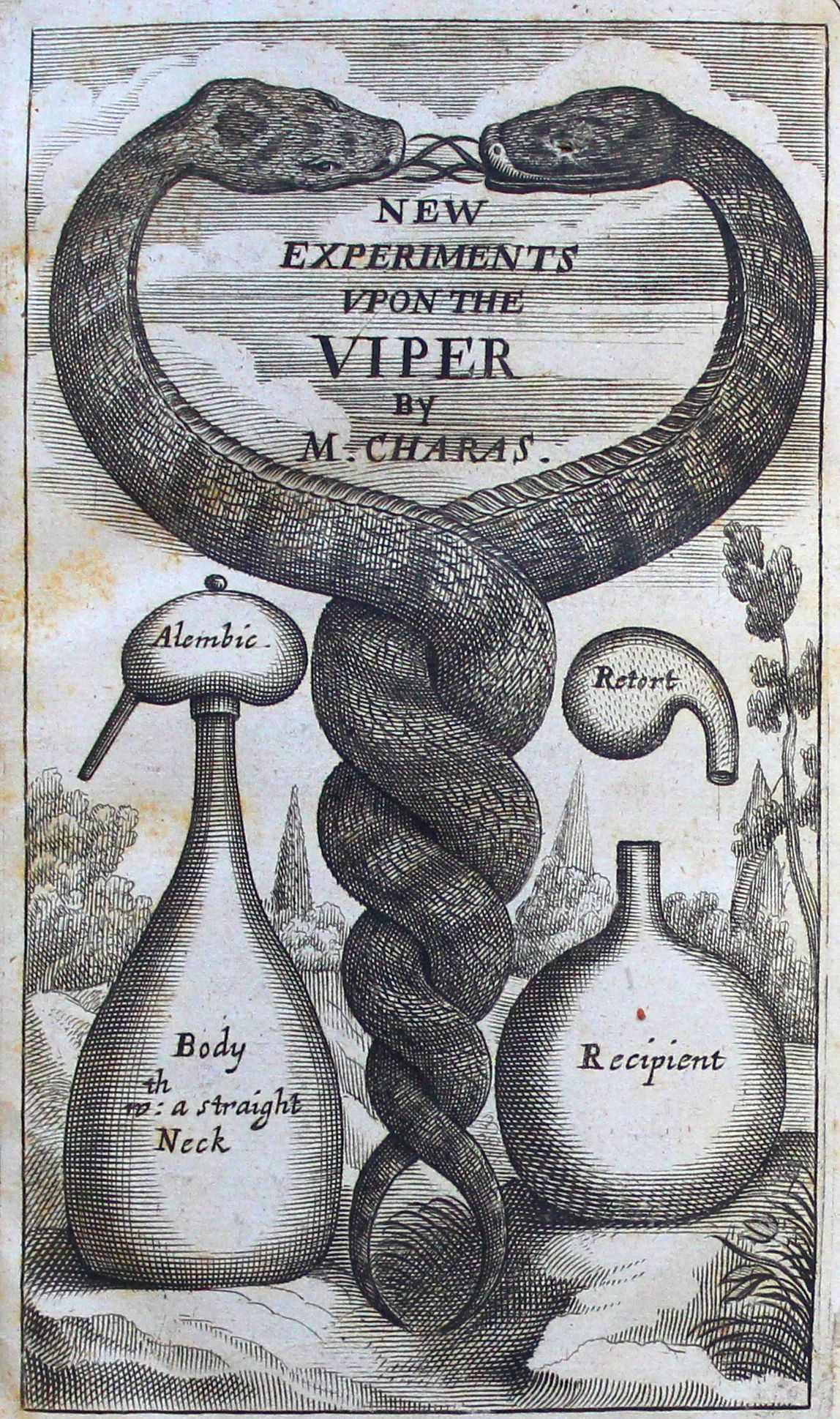

Next comes an entire work dedicated to snakes by French apothecary Moyse Charas (1619-1698). Charas, whose work was first published in French in 1669 under the title: Nouvelles expériences sur la vipère, was interested in the nature of snake venom and the ways in which extracts from snakes could allegedly be used to treat various ailments, such as smallpox and leprosy. Our library holds an English translation from 1670.

Title page of New Experiments upon Vipers by Moyse Charas, London, 1670 (Shelfmark: Thackeray.VIII.11.12)

In addition to the main title page, it contains a glorious added engraved title page, showing entwined serpents.

Added engraved page of New Experiments upon Vipers by Moyse Charas, London, 1670 (Shelfmark: Thackeray.VIII.11.12)

The book includes detailed anatomical drawings on folded plates at the rear, one of which is shown below.

Folded anatomical plate from New Experiments Upon Vipers by Moyse Charas, London, 1670 (Shelfmark: Thackeray.VIII.11.12)

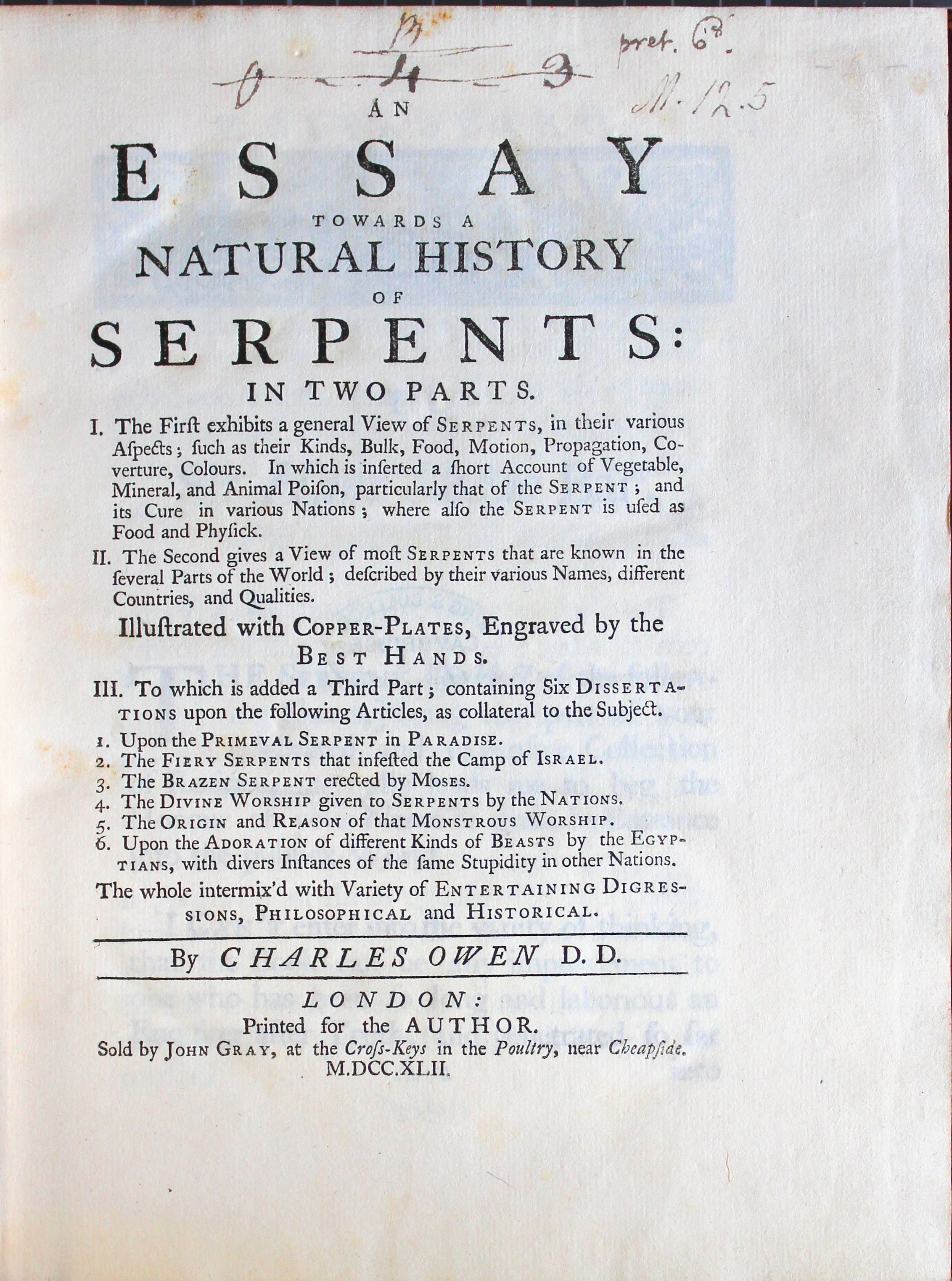

Another book focused entirely upon snakes is An Essay towards a Natural History of Serpents by Charles Owen (d.1746). Owen was a clergyman rather than a scientist, and his (often inaccurate) information is drawn from various biblical and mythological sources. The title page describes the contents in a fair amount of detail.

Title page of An Essay towards a Natural History of Serpents by Charles Owen, London, 1742 (Shelfmark: Bryant.M.12.5)

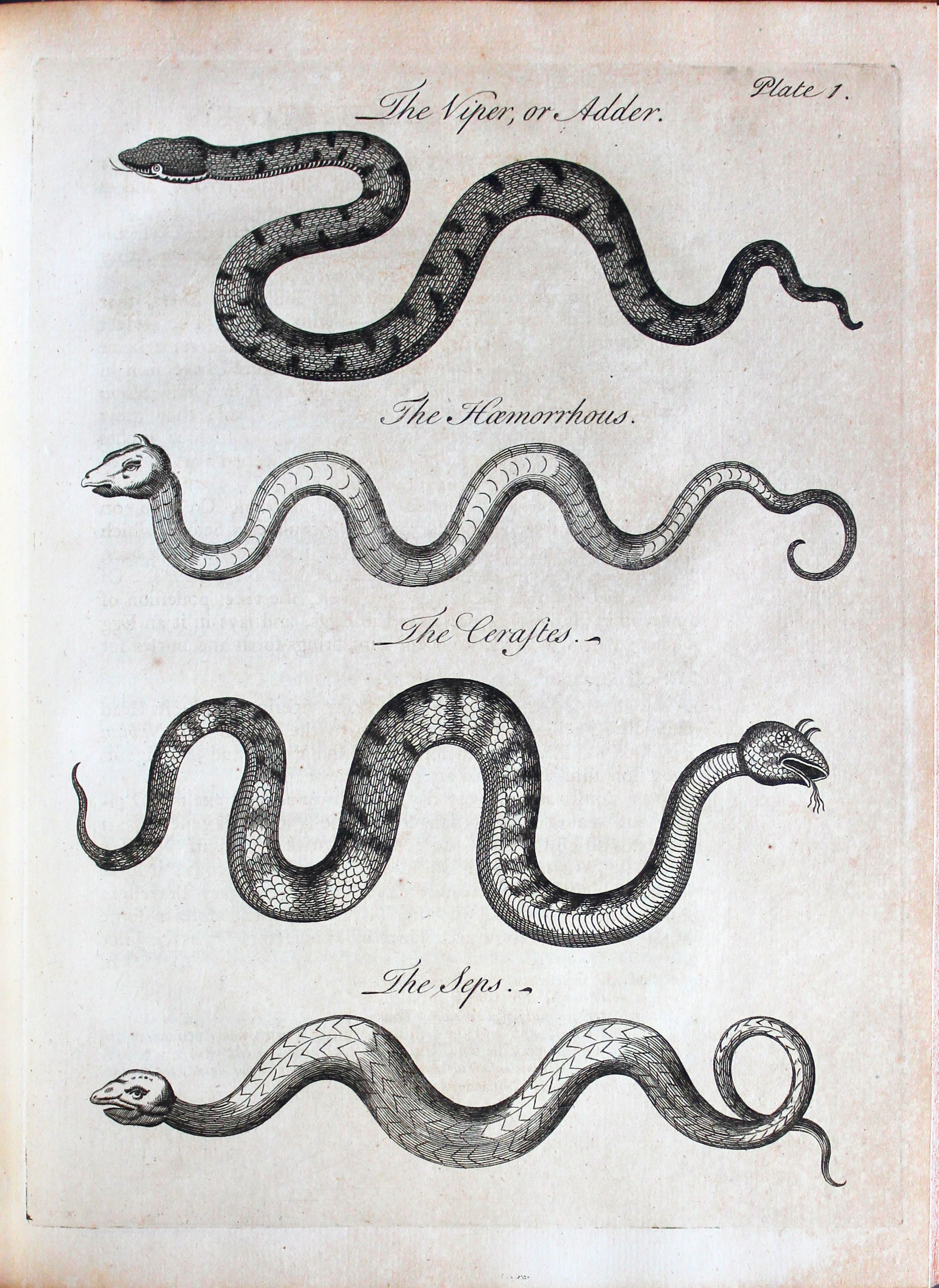

The illustrations in this volume are great fun, and very striking, as can be seen from the examples below. The snakes all have very expressive faces.

Plate 1 facing page 54 from An Essay towards a Natural History of Serpents by Charles Owen, London, 1742 (Shelfmark: Bryant.M.12.5)

Plate 3 facing page 78 from An Essay towards a Natural History of Serpents by Charles Owen, London, 1742 (Shelfmark: Bryant.M.12.5)

The plate above includes the depictions of a mythical creature: the Basilisk (here conflated with the Cockatrice), which the text describes as the Little King of Serpents, hence the crown upon its head.

Plate 6 facing page 142 from An Essay towards a Natural History of Serpents by Charles Owen, London, 1742 (Shelfmark: Bryant.M.12.5)

Other natural history books provide beautiful colour images. Below is an illustration of a double-headed snake from a work chiefly devoted to rare birds, by noted English ornithologist George Edwards (1694-1773). Edwards widened the scope of his work to include other unusual creatures, including reptiles, and described this snake thus:

I did not propose at first in this Natural History to exhibit monsters, but our present subject (considered even with a single head) may be looked on as a natural production of a species little or not at all known to us.

We now know that this phenomenon comes about in some snakes in a very similar way to the development of human conjoined twins, and is not a sign of a separate species.

Double-headed snake. From the plate facing page 207 of volume 4 of A Natural History of Uncommon Birds by George Edwards, London, 1743-51 (Shelfmark Keynes.P.6.11/1)

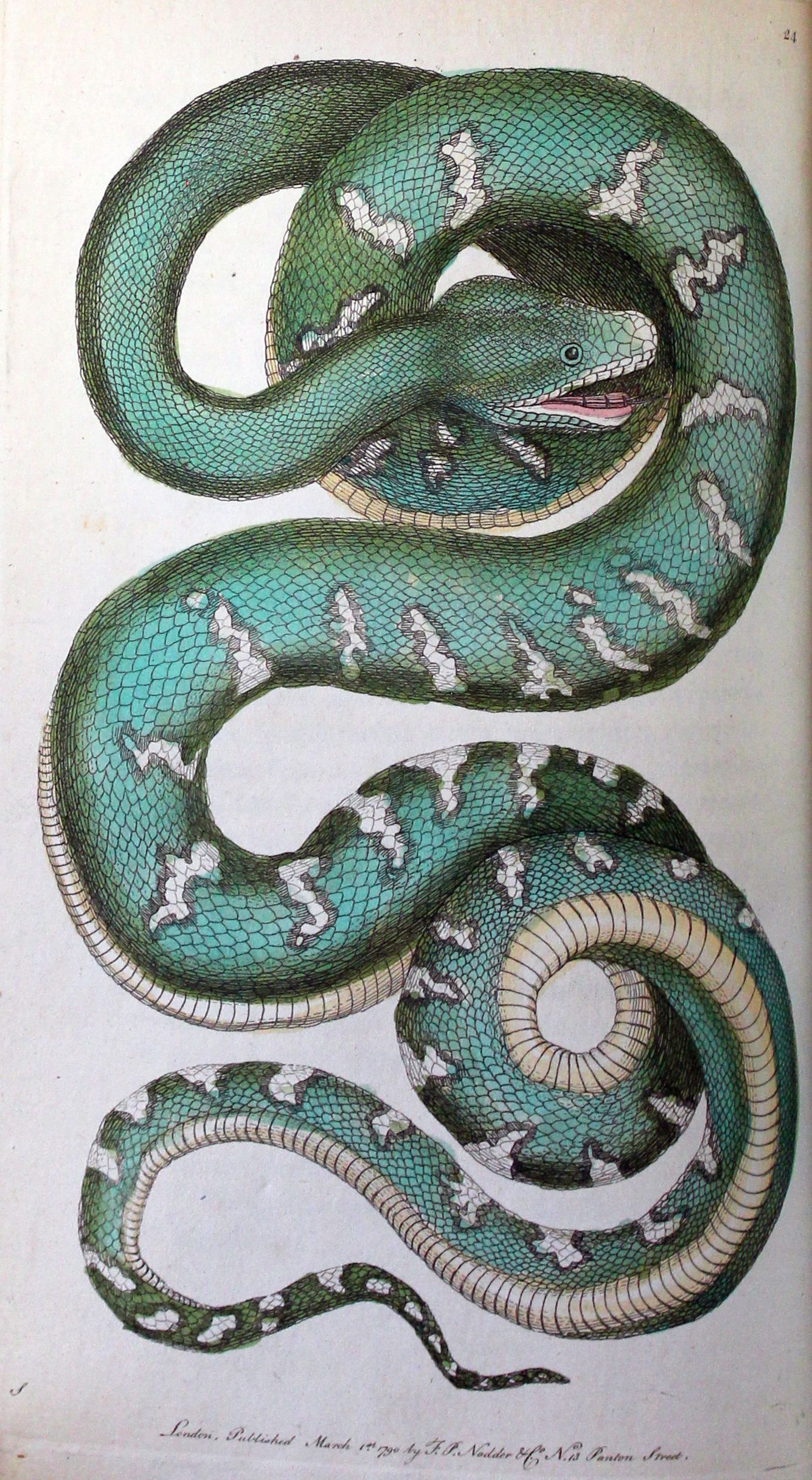

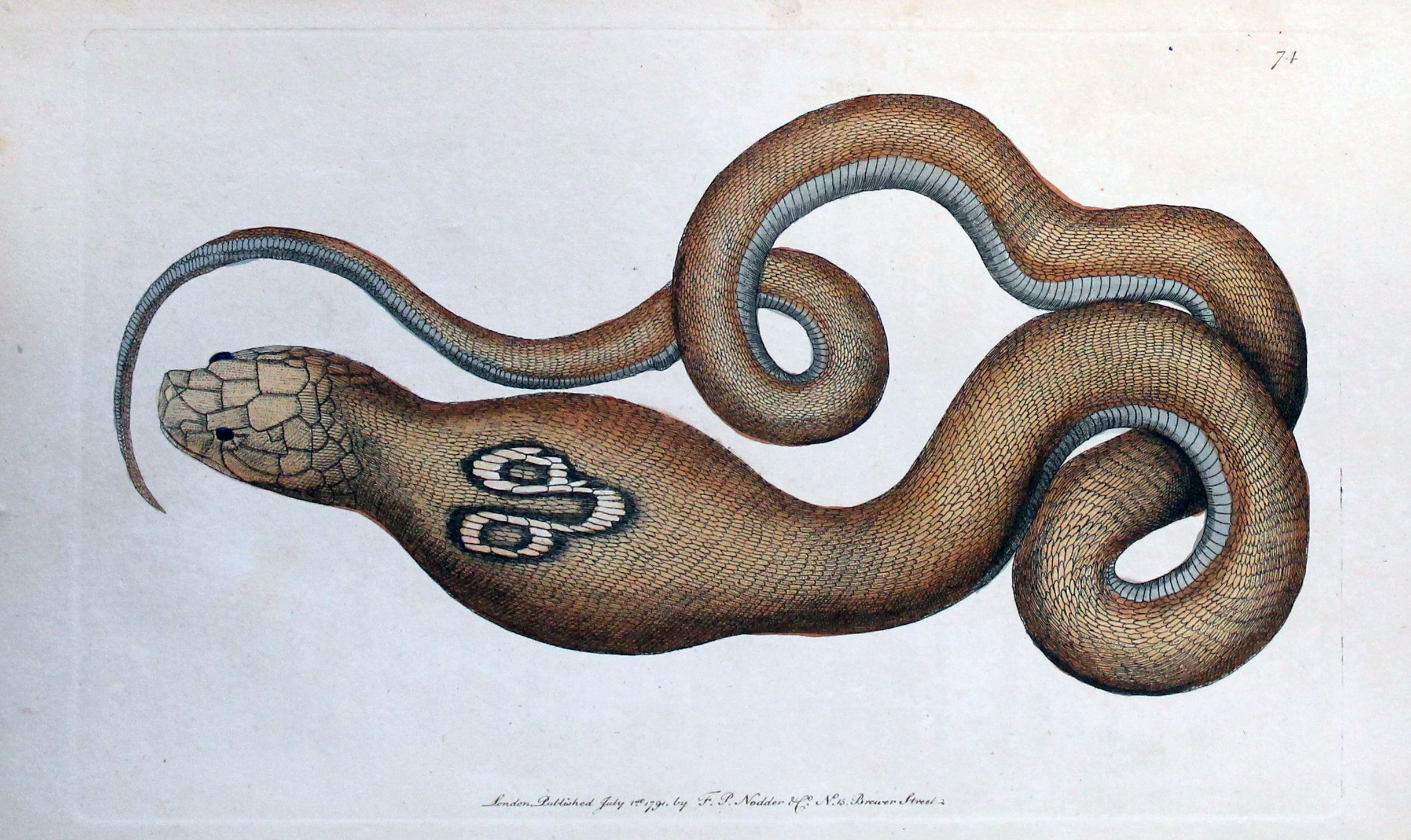

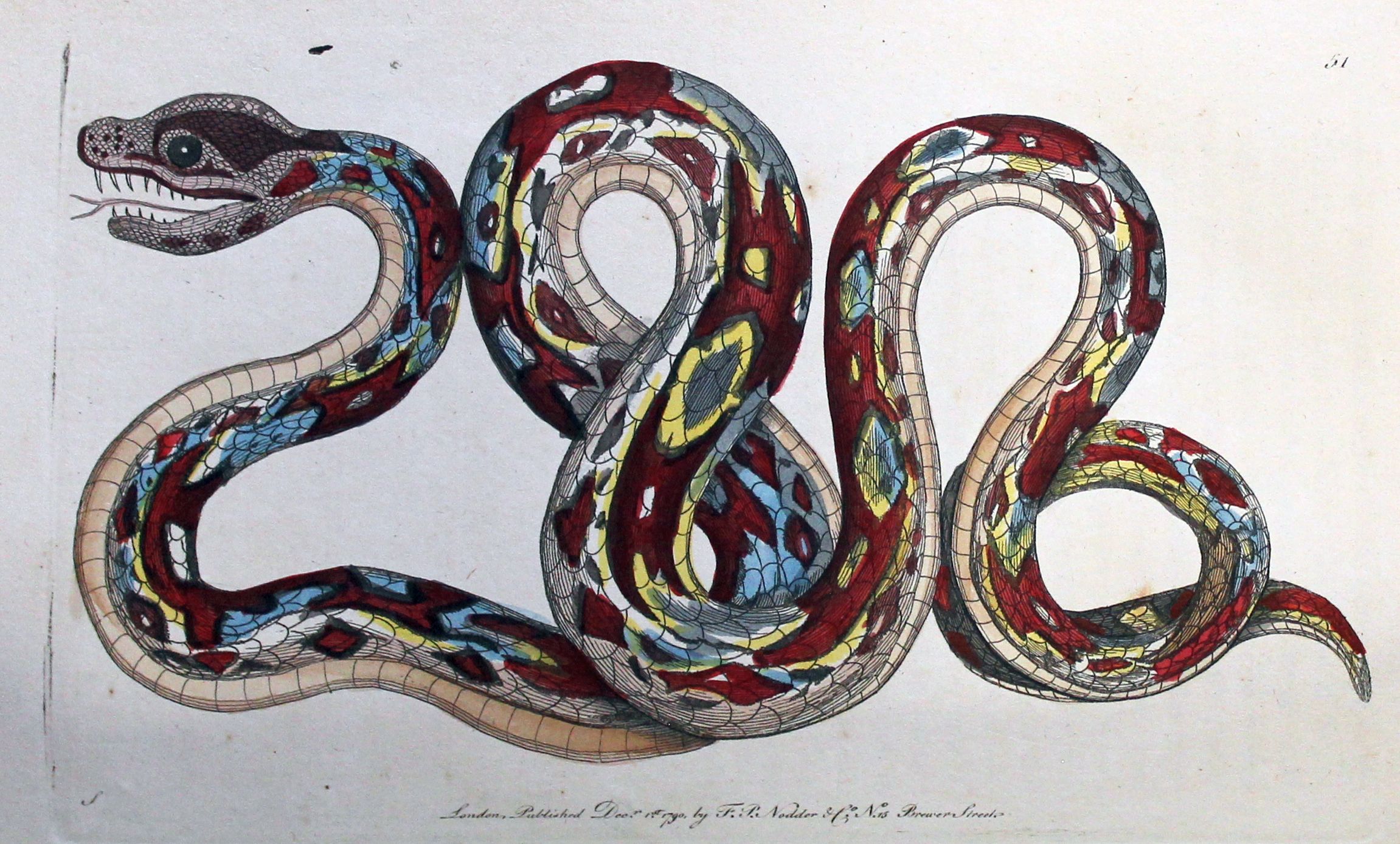

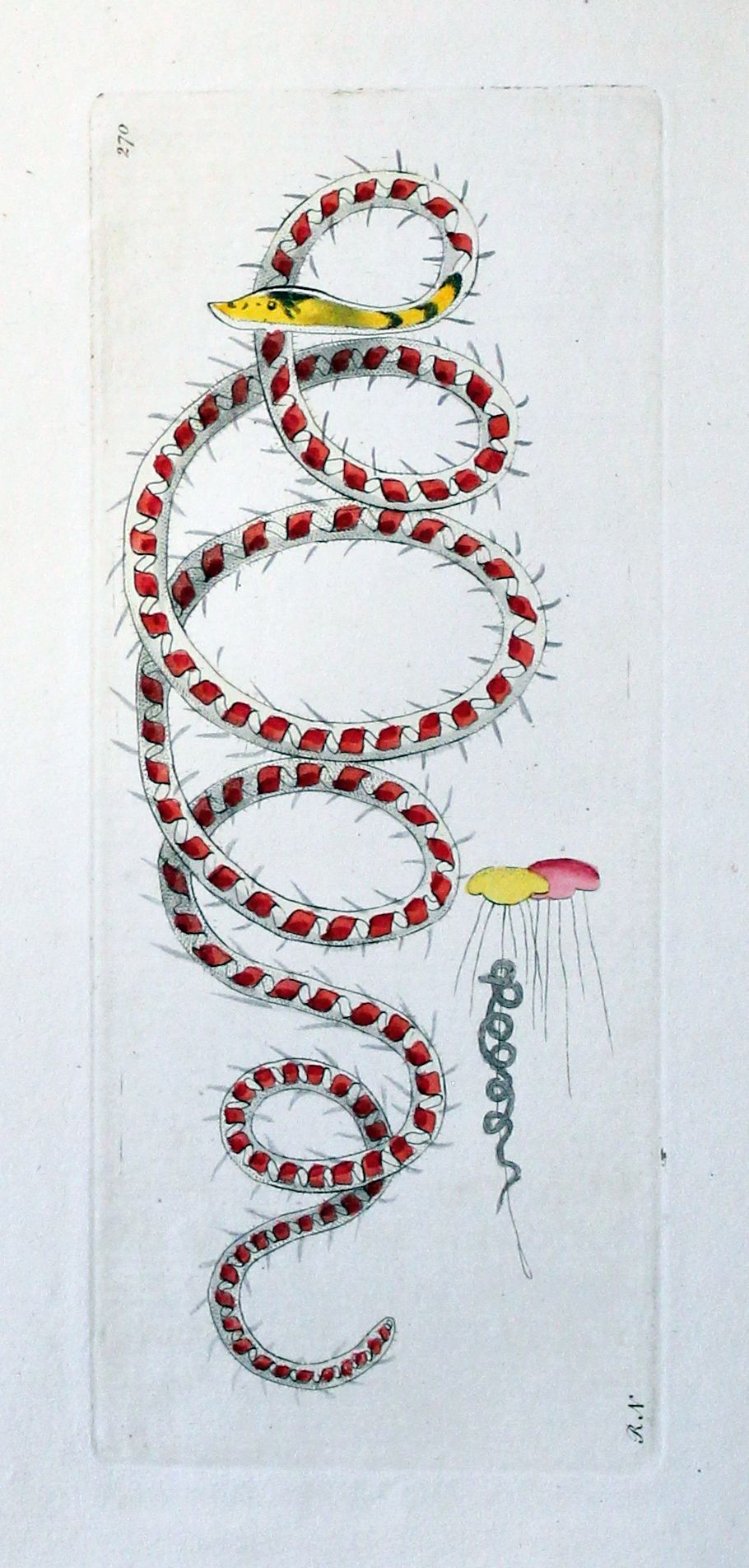

Leafing through a multi-volume miscellany of the natural world by biologist George Shaw (1751-1813), we were spoilt for choice for great images to highlight. Shaw was a Fellow of the Royal Society and sometime keeper of the Natural History Department at the British Museum. He described many new species of amphibian and reptile. Below are just a few of the many vibrant illustrations of snakes contained within Shaw’s Miscellany.

Painted snake. Plate facing fol. C2 recto in volume 1 of The Naturalist’s Miscellany by George Shaw, London, 1790 (Shelfmark: Thackeray.IV.2.2)

The canine boa. Plate 24, facing fol. L4 recto in part 1 of The Naturalist’s Miscellany by George Shaw, London, 1790 (Shelfmark: Thackeray.IV.2.2)

The spectacle snake. Plate 74, facing fol. 2K4 verso in part 2 of The Naturalist’s Miscellany by George Shaw, London, 1791 (Shelfmark: Thackeray.IV.2.2)

The Great Boa. Plate 51, facing fol. Z5 recto in part 2 of The Naturalist’s Miscellany by George Shaw, London, 1791 (Shelfmark: Thackeray.IV.2.2)

The Gilded Snake. Plate 209, facing fol. O8 recto in part 6 of The Naturalist’s Miscellany by George Shaw, London, 1795 (Shelfmark: Thackeray.IV.2.4)

The Serpentiform Nais. Plate 270, facing fol. E4 recto in part 8 of The Naturalist’s Miscellany by George Shaw, London, 1796 (Shelfmark: Thackeray.IV.2.5)

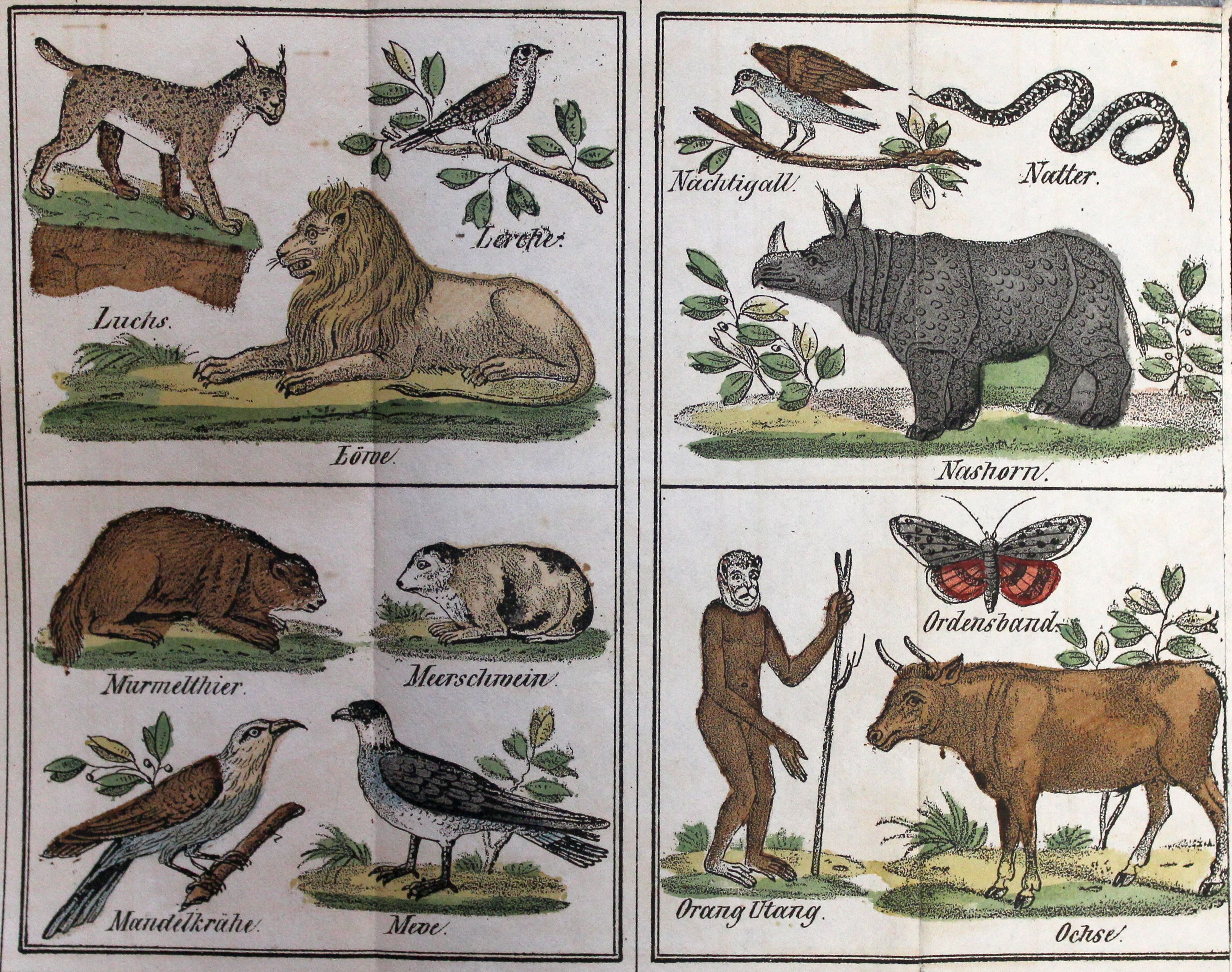

Finally, a little snake appears in a charming little German alphabet book from our Rylands Collection of children’s books. This tiny book, dating from the latter half of the nineteenth century, consists of three strips of paper stuck together and folded accordion-style. The German word for snake being “Natter”, the snake comes under the letter N in this sequence, alongside a Nashorn, or rhino, and a nightingale.

We hope you have enjoyed this survey of snakes within the pages of our rare book collections, and that you have a wonderful New Year!

References

Joscelyn Godwin, Athanasius Kircher: A Renaissance Man and the Quest for Lost Knowledge , London, 1979.

Paula Findlen (editor), Athanasius Kircher: The Last Man Who Knew Everything, New York, 2004.

AC